What I’m teaching men is how to show up as themselves — genuine, transparent, truthful, willing to be vulnerable — and to practice that honesty first in safe settings before bringing it into the wider world, including with women. It’s not about becoming rude or unkind; it’s about developing authenticity, strength, direction, enthusiasm, and crafting a life that reflects your own values. Today’s guest is Dr. Robert Glover — the person I’ve been referring to on this channel for five years — who guides men to stop playing the “nice guy” and start being authentic. He’s the author of No More Mr. Nice Guy, a book I strongly recommend to anyone who recognizes the patterns of the “nice guy” dynamic. Robert, it’s a pleasure to have you here. Anna, thank you for inviting me. I’ve been looking forward to this conversation — I love your podcast’s name. I’m glad we finally connected. I’ve been recommending your book since my son introduced it to me about five years ago; it’s had a major cultural impact. I checked how many readers have reviewed it on Amazon — it’s clear the book has reached a lot of people. It still feels relevant. Honestly, I’m still processing what that means — as you say, being yourself can have a surprisingly positive ripple effect. For those who haven’t encountered No More Mr. Nice Guy, it articulated something that needed saying: the overly accommodating man often isn’t attractive to women and can end up feeling hollow. How did you come to specialize in this? Well, it’s an interesting story. I just finished a client call about an hour ago and, at the end, he said he needed to listen to the book again. He asked whether I would rewrite it now that it’s been out roughly 25 years. I explained that eight years ago my publisher asked about an update and I opted for minor corrections and a new preface. I liked the book as it was. Fifteen years after publication — now twenty-five — the royalties keep increasing, so apparently the message is still needed, and more people are learning about it. The younger generations even have a label for this behavior — they call it “simping.” I began addressing these patterns thirty years ago after working on my own “nice guy” issues and as a marriage and family therapist hearing the same stories from many men: “I’m one of the nicest guys you’ll meet,” they’d say. “I try to please my wife, I take care of her kids, I give her what she wants, but it’s never enough — she’s upset, she’s not interested sexually, I thought we were close.” I realized I wasn’t alone and formed a No More Mr. Nice Guy men’s group that met every other week. I wrote lessons and short chapters for the men — initially not intending to write a book, but writing to make sense of things. People eventually urged me to put it together as a book and even suggested I could go on Oprah. That made me hesitate, but I kept writing and the book eventually appeared around the turn of the century as an ebook and in print in 2003. Since then it’s continued to sell more every year. At the time, nobody had really framed men’s patterns of codependent behavior in a way that spoke directly to men. I consciously avoided the word “codependency” because it had evolved out of addiction literature and tends to suggest a certain gendered image — often women as caretakers of addicted men. I wanted men to pick up the book without thinking, “I’m not a woman, how could I be codependent?” So I named the pattern “nice guy syndrome.” I also prefer another phrase: “borrowed functioning” — when a person’s sense of identity, value, or purpose depends on something or someone external. For example, if someone’s sense of worth comes from people loving their dog, from having an attractive partner, or from being the person who always fixes someone else’s problems, that’s borrowed functioning. You can feel valuable as long as that external thing remains, but if it disappears, your identity collapses. Paradoxically, when your identity is tied to fixing or rescuing someone, you end up invested in them staying unwell, because their need for you maintains your role and sense of purpose. If they truly healed and no longer needed your help, you’d risk losing that role and being left without that source of identity. So yes, short answer: I’m a recovering nice guy. I’ve seen this pattern in my own life and in many clients. Why are women often not attracted to “nice guys”? There are a few reasons. First, who is attracted to a rescuer — someone who treats you like you’re broken and must be saved? A person might accept gifts or help, but that doesn’t necessarily create sexual attraction. A deeper reason is that nice guys approach relationships from a place of lack: they need the relationship to feel themselves, so they don’t bring a strong sense of “me” to the partnership. Nice guys are chameleons — they morph into whatever they think others want so they will be liked or loved, and they hide parts of themselves that might provoke rejection or punishment. That pattern, learned in childhood, leaves little of an autonomous self. Many nice guys are drained rather than resourced: they give so much to others that they don’t nurture themselves or cultivate people who give back. They enter relationships from a needy, empty place, hoping the partner will fill them up — and women tend to sense that energy. Mark Manson’s book Models, which promotes attraction through honesty and warns against neediness, was influenced by No More Mr. Nice Guy; he once said he wouldn’t have written Models without having read my book. When a man is well-resourced — with friends, purpose, regular self-care and activities that nourish him — he’s overflowing, not empty, and that vitality is attractive. Nice guys, however, are often depleted and approach sex and intimacy covertly, expecting the partner to plug the hose and fill them up. Women tend to reject the needy energy, not the man’s sexual invitation per se. I call the hidden expectation that fuels nice-guy behavior the “covert contract”: the unspoken bargain, “I’ll do X for you if you’ll give me Y (affection, appreciation, sex, no anger) in return,” without ever stating the terms. When the expected return doesn’t happen, frustration and resentment build. That phrase — covert contract — really resonated with me when I first read it. It stuck with me years later; it’s like making a secret, manipulative deal with someone. I experienced that dynamic in my own dating — when someone is hard to get, chasing rarely helps; better to let things evolve naturally and pay attention to signals. For people who’ve experienced trauma or disrupted early attachment, it’s easy to latch onto someone and expect them to fix unmet needs, but that often derails a genuine relationship. We tend to be unconsciously drawn to partners who repeat familiar, even painful, family dynamics. I once read in a codependency text that we’re often attracted to people who carry the worst traits of both our parents. That insight highlights how relationships become powerful engines for personal growth because they repeatedly trigger childhood wounds. From a systems perspective — my training as a marriage and family therapist — a relationship exists the way it does because both partners unconsciously need it to be that way. The projections and reactions we have toward our partners are information about unresolved issues from our past; if we notice them and do the work, relationships can catalyze deep change. My general advice to couples and singles has always been the same: whatever you think the opposite sex can do for you is usually mistaken. People are not the solution to your sense of lack. One of the healthiest moves is building same-sex friendships: women often maintain strong bonds with other women, and that’s protective. Men, however, typically let same-sex friendships fade when they enter committed relationships, or they never cultivate them in the first place. Yet a solid network of male friends gives men resources to handle conflict and loneliness without clinging to a partner. If a man’s only support is his partner and she withdraws or is away, he can quickly fall into desperation to save the relationship. When my earlier marriages ended I discovered that most of my friends were couple-friends who didn’t want to get involved. After my third marriage ended I did things differently: before marrying again I joined a men’s program, built friendships intentionally, and went into my next marriage with a circle of male friends. That work — building 25–50 men I could call on — deeply strengthened my later marriage. Nice guys often lack that kind of male support and instead rely on validation from women. The dynamic is not limited to straight men; gay men can exhibit “nice guy” patterns too. In one workshop in LA several gay men in the audience recognized the same categories and the same relationship traps. I live in Puerto Vallarta in a gay-friendly community and many of my close friends are gay men; they confirmed that these dynamics translate across sexual orientations. Finally, on causes: there are many contributors. Cultural factors — historical shifts like the Vietnam era reaction against fathers, feminism, educational systems, media messages, broken or distant father–son bonds, mothers who overinvested in their sons — all play roles. In younger generations I hear that many men actually had fathers who were “nice guys,” and those fathers taught sons primarily to avoid upsetting their mothers. Add contemporary trends — the #MeToo movement, conversations about toxic masculinity, and social messages that make some men afraid to take any stand — and you have many men who end up passive and conflict-averse. Technology and culture also encourage isolation: social media, online gaming, and virtual interaction often replace real, challenging, in-person male initiation and bonding experiences. Historically, boys were separated from mothers and initiated into manhood through rites of passage; those rituals signaled to the community that the young man had earned a place and competence. Without those experiences, many young men lack the qualities that traditionally attracted women. My approach is to create safe spaces where men can connect with other men, practice vulnerability, face challenges, and learn to tolerate discomfort — which builds competence and presence, qualities that feel attractive. For many men, part of the work is reclaiming that ability to be comfortable in one’s own skin. As I mentioned, the dynamic appears in gay men as well: the same patterns, when the genders are reversed or when sexual orientation is different, still fit. The book has helped many people recognize the pattern when they hear the name for it. My own son suggested I read the book when he was around twenty-one after his first serious breakup; once you learn the label you start seeing the pattern everywhere — in fathers, in friends, in past relationships — and you begin to understand the mix of anger, passivity, and resentment that often lies beneath. Despite a difficult marriage history, my ex and I did manage to co-parent effectively, and recognizing these patterns can be the first step toward healthier relationships.

He didn’t lecture me — he helped me see things differently. He didn’t say, “You must have strict boundaries with your child” in a preachy way, but some of what we discussed was about not exposing everything to them. For example, when my son was little and I was upset, he’d watch and listen intently. When I launched Crappy Childhood Fairy, he filmed all my YouTube videos and my courses — he was a teen then, about 17 or 18 — and he absorbed a lot of my ideas about dating and healing trauma. That was a privilege for him.

When I was divorcing his father, my son was four and the conflict was vicious. The kids went back and forth between houses, and during that time I had serious medical complications after a surgical error that led to 14 major operations. A few years later I dated a man who turned out to be an addict and, after I ended the relationship, he took his own life. There was significant trauma in our home. I remember one particular police officer who came to the scene when the children were buckled in the car. I can’t recall his face, only the broadness of his chest and shoulders, but he gripped my shoulders and said, “Ma’am, your children will take cues from how you react. They need to see that you’re strong and can handle this.” That simple clarity saved me.

After that I made it my mission to demonstrate resilience to my kids — to show them I could cope and that what happened wasn’t going to define our future. They were too young to fully understand, so I worked hard to be the steady parent. Eventually I remarried, but my husband didn’t meet the children for a year; we wanted to be sure our relationship was solid before introducing him. In retrospect I realized I had added stress to my children’s lives during those early years, which made them anxious about my wellbeing. My younger son was small enough that he internalized less, but my older son carried a lot; he became my little protector.

One moment I’ll never forget: I must have been three or four, he was small, and I was crying from the pressure and pain of that time. He cupped my face, turned it toward him, and said, “Don’t be sad, Mama. Don’t be sad.” That touched me so deeply I forced myself to compose myself and take a big step forward in my healing. Years later, when his father and I argued — we raised our voices over something as mundane as money, as co-parents sometimes do — my then-grown son burst into the room and said, “Don’t fight. Don’t fight, you guys.” It was the same instinct to protect and soothe me, now in his twenties.

I did everything I could to correct that old dynamic. You can’t simply erase a wound someone else has carried, because ultimately they have to heal themselves, but I apologized for how my behavior had pushed him into caretaking. I told him plainly that he was free — that he no longer had to tend to me, that I had a partner and that he could be a kid, a young man, and not my emotional guardian. I felt good about finally offering him that freedom. Reading your book prompted me to realize I needed to liberate him entirely from that sense of obligation.

We’ve had a lot of laughs over the phrase “monogamy with your mom,” which Robert coined. I made a playful video riffing on “mono-mom.” We joke: when he says he and his girlfriend are going up to the Russian River, I teasingly ask, “What about me?” It’s become a running gag between us. I could probably spend two or three conversations unpacking the “monogamy-to-mom” idea in depth.

I receive letters a few times a week from people about relationships. One woman wrote saying she was dating a man who spent all his Sundays with his mother and used Saturdays to fix her things — a pattern that lasted years while the mother openly disliked the girlfriend. I told her frankly that it didn’t sound like a healthy match and suggested she read your book to see if it described the dynamic she was experiencing. Frequently I don’t hear back, but these letters keep this issue in front of me. As I’ve said before, a woman who marries a “nice guy” has a difficult road as well.

Since you brought up “mom-monogamy,” that’s one of the most common questions I get about my work — people ask about No More Mr. Nice Guy and what being “monogamous to mom” means. I struggled with it myself when I first tried to explain it, and it can be a tricky concept to convey. Fiction can illustrate it powerfully: I often recommend novels because storytelling is one of the oldest ways we learn about ourselves — the hero’s journey and morality tales teach us lessons that short social clips never will. Read fiction.

Think of Fight Club: the line about “a generation of men raised by women” is memorable — it suggests that looking to another woman for fulfillment isn’t the solution. Chuck Palahniuk’s novels also capture this theme. In his book Choke, the protagonist has a mentally unstable mother who believes he was conceived immaculately; the son remains devoted to her to a damaging degree. There’s a line that resonated with me: when your mother is your first spouse, every other woman feels like a mistress. That sums up the “monogamy-to-mom” dynamic — a boy becomes parentified, called on to soothe his mother, to be unlike his father, to solve her problems and stop her from crying.

My mother told me she was raising her sons to be different from our father, and as I grew older and began to set boundaries, I found myself saying, “I can talk about anything with you, but not about Dad anymore.” She used guilt, tears, anger, and passive-aggressive tactics so effectively that I stopped speaking to her for fifteen years. She treated me like her property: she told my partners things like “I saw him naked before you did,” staking a claim. After my father’s stroke and death, my mother and I finally worked through a lot of that, and now, fifteen years on, our relationship is much healthier and reciprocal — but it took years of healing. For a long time every romantic relationship felt like an act of betrayal to that primary bond with Mom, so no other woman could ever be fully embraced.

When Mom is experienced as the first spouse, men often can’t form deep, healthy partnerships later. Either they seek out women with problems they can fix, women with addictions or infidelities, or partners they don’t truly love because they’re afraid of having a better relationship than Mom ever had. Those patterns show up as choosing unavailable or damaged partners, or even finding same-sex relationships that mirror the caretaking dynamic. When a boy must constantly attend to his mother — emotionally or practically — it creates an attachment wound. That’s why you telling your son “you’re free” is so important.

I’m still working through my own issues. Recently I did an MDMA-assisted therapy session in Austin with a coach; much of the work focused on childhood trauma and how I sacrificed myself to keep peace between my parents and to stay close rather than explore and socialize as a child. My dad imposed strict curfews and rules, and because I was “raised by women” in a sense I didn’t feel like I could be the kind of adolescent who pursued romantic or sexual experiences openly. Instead I became a “nice guy,” doing favors, solving problems, listening — all the behaviors that masked any sexual motives and kept me loyal to that early maternal bond. That pattern produced many problematic relationships because I wasn’t allowed to fully invest in a healthy, reciprocal partnership.

This tendency to gravitate toward unavailable or troubled partners is something I teach about with people who experienced neglect or abuse in childhood. Many of my followers are women who keep finding unavailable or inappropriate partners — a pattern that’s hard to recognize because it becomes familiar. For men, becoming able to see red flags and also to feel drawn toward healthy signals is a long process. People often feel ashamed around functional, well-adjusted people, which may be partly a nervous-system response.

When I started dating again in my late forties after two long marriages that each lasted 25 years, I noticed I was repeatedly attracted to unhappily married women or women who offered dramatic histories of failed relationships. My first real love was married and unhappy, and I unconsciously took on the savior role: I wanted to be different from other men and fix things. I learned to walk away once I recognized the pattern, because over time some of these women’s stories made me feel sympathy for their exes and realize that perhaps the common denominator in their romantic history was the woman herself. If I stayed, I ended up being listed among the “horrible exes.” Recognizing the pattern and leaving was the crucial step.

People aren’t usually in control of who they fall in love with; attraction can feel automatic and irrational. Changing the character of those attractions is a deep transformation — often below conscious language and cognition — and it can take a very long time. It may even involve biological or evolutionary elements; we don’t need to fully know why everything happens. What matters is what we do once we notice our patterns. In coaching, I’ll sometimes give clients one simple task: observe your tendency to become codependent with a partner or family member. Don’t fix anything; just notice. Developing the capacity to observe yourself is the core engine of change.

You asked about the programs I offer men now. They’re solid and well received. I recently hired a virtual assistant to help manage my overflowing inbox — my professional account had about 2,800 emails — so I’m finally catching up on messages that might have been missed in the past. That’s why sometimes invitations fall through the cracks; it’s not about the sender’s worth but about sheer volume.

My work with men includes several main offerings. Integration Nation is a membership program for men I started about two years ago; it’s international and currently has roughly five hundred members. We host more than seventy calls a month focused on building community and connection, because many men lack meaningful male friendships. I lead a weekly Thursday call where I either teach a lesson or interview a guest — I’ve interviewed people like Dr. Jed Diamond, Mark Manson, and Gary Chapman (author of The Five Love Languages). The program includes breakout rooms and nine weekly “tribe” calls led by certified No More Mr. Nice Guy coaches, so men can meet at different times each week. There are also clubs and other ways to plug in. The essence is creating space where men can be honest and vulnerable with one another.

We do an annual in-person conference; the first one was held in January, and the next is planned for Playa Girón, Mexico. Seeing men connect face-to-face — sharing meals, doing practices, having fun — is powerful. One man told me, “I’ve never trusted men,” but after getting involved he wanted more retreats and workshops. Many men carry father wounds or have been bullied, so they often seek nurturing and validation from women instead of from peers; our work helps them process father-related pain and build male friendships. On calls we sometimes introduce ourselves with our first name followed by “son of,” which can be triggering for some, but the point is to bring awareness to what’s unresolved in relation to fathers so the work can begin.

Besides Integration Nation, I run a group mentorship program built around a filmed 12-unit curriculum on Nice Guy recovery — each unit is about 90 minutes — designed as a six-month program with weekly calls: I teach every other week and coaches lead interactive small groups on the alternating weeks. I also host in-person weekend workshops at my house, limited to about eight men, where we get deep into whatever’s present for the group — relationships, dating, boundaries, monogamy-to-mom, prioritizing needs, healing the father wound. I tell participants that by Sunday they’ll feel like frat brothers after having done the vulnerable, connective work together. Men often stay in touch after these events and return for more. In addition, I travel frequently to speak to men’s groups around the world — I’ve been to Japan, Florida, Austin, and have trips planned to Australia and Copenhagen.

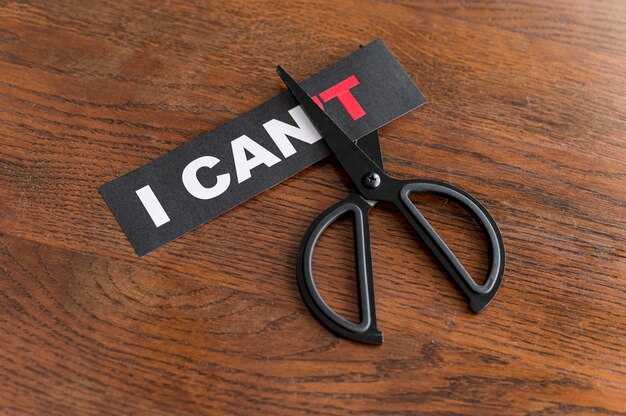

A common question I get is: “Does this mean we should stop being nice? Are we supposed to become mean?” The title No More Mr. Nice Guy can be provocative, but it’s really about becoming authentic and integrated. I talk about the “integrated man” — someone who has reconciled their light and shadow, their emotional and practical selves, rather than flipping into a caricature of “nice” or “jerk.” My motto for Integration Nation is “good men doing better.” It’s not about perfection; it’s about growth from a place of self-acceptance. When you like and accept yourself you’re motivated to be more patient, to set boundaries, to take care of your needs, to show up differently in relationships. That’s much more effective than doing things from shame or people-pleasing.

People often worry that teaching men to be authentic will produce more cruelty, but the opposite happens: when men are honest about who they are, live life on their terms, and attract people who appreciate them as they are, relationships become clearer and healthier. Women tend to like that kind of man — someone comfortable in his own skin, who knows where he’s headed and appears to enjoy the journey. I don’t teach men to be manipulative or unkind; I teach them to be whole, to stop performing for approval, and to live with integrity. That authenticity makes people more attractive naturally.

Interestingly, when Barnes & Noble briefly ventured into publishing, they wondered if a title like mine would provoke backlash, maybe from women who saw the wording as harsh. In practice, the letters I get from women tend to thank me. Women read the book, recognize patterns in their sons or partners, and find the framework helpful. The few angry letters I’ve received over the years are usually long missives from women whose partners read the book and then left — they blame me for the breakups. I don’t respond; their reaction tells them what they need to do next. Overall, women appreciate men who are authentic, purposeful, and comfortable, and that’s what I aim to help men become: men who know who they are, are heading somewhere, and seem to be enjoying the ride.

So in short: the goal isn’t to teach men to stop being kind — it’s to help them stop being performatively “nice” in ways that cost them their authenticity. It’s about helping them do better from a place of self-respect and honesty. Thank you for inviting me to talk about this.

착한 남자 증후군: 남성 공생 의존과 왜 관계를 망치는가">

착한 남자 증후군: 남성 공생 의존과 왜 관계를 망치는가">

관계 전문가가 연결의 비밀을 밝힙니다: Dr. Sue Johnson">

관계 전문가가 연결의 비밀을 밝힙니다: Dr. Sue Johnson">

Are You Surrounded by Bullies? The Hidden Reason You Let Them In">

Are You Surrounded by Bullies? The Hidden Reason You Let Them In">

파트너의 행동이 트라우마와 관련이 있지만, 그래도 괜찮지 않다.">

파트너의 행동이 트라우마와 관련이 있지만, 그래도 괜찮지 않다.">

The STRONGEST Sign An Avoidant Still Loves You Deeply">

The STRONGEST Sign An Avoidant Still Loves You Deeply">

If You Shut Down During Conflict, Watch This">

If You Shut Down During Conflict, Watch This">

당신의 파트너가 이런 문구를 말한다면, 그들은 회피형입니다.">

당신의 파트너가 이런 문구를 말한다면, 그들은 회피형입니다.">

Until This One Shift Finally Made the Avoidant Come Back | Mel Robbins Motivational Speech">

Until This One Shift Finally Made the Avoidant Come Back | Mel Robbins Motivational Speech">

치유를 위해선 슬픈 이야기보다 정상적인 행동이 더 강력합니다.">

치유를 위해선 슬픈 이야기보다 정상적인 행동이 더 강력합니다.">

파트너는 과거에 대해 알아야 하지만, 데이트를 시작한 경우라면 어떻게 해야 할까요?">

파트너는 과거에 대해 알아야 하지만, 데이트를 시작한 경우라면 어떻게 해야 할까요?">

부정행위는 이기적인 겁쟁이들을 위한 것 (저 같은).">

부정행위는 이기적인 겁쟁이들을 위한 것 (저 같은).">