Maybe people labeled you as needy when what actually happened was you were left alone too many times. Maybe you were told to quiet down even though your body was shouting that something was off. This isn’t all in your head. These are the cues of a nervous system that learned to hunt for danger from an early age. Many of these signs tend to appear more often in women — not always, and trauma doesn’t single out anyone. Everyone carries it in their own way. Men sometimes show different patterns, like sudden rage, workaholism, or emotional numbness. Not because men feel less, but because trauma shapes itself around the survival strategies someone learned. For some men that meant shutting feelings down altogether. Other reactions appear across genders — hypervigilance, panic, trouble trusting others, staying stuck in harmful relationships, withdrawing when overwhelmed, or feeling like everyone else received the instruction manual for life except you. You didn’t get it. But there are patterns that more commonly show up in women — trouble asserting boundaries, chronic people-pleasing, apologizing constantly, perfectionism, and an intense fear of being rejected. These are common among women. They are not failures or inherent female flaws; they are adaptations driven by trauma in response to what was hard for you. And the hopeful part is that they can be changed. I want to explore that now.

When I was in college I had no option but to overperform. I lived alone, moved to California, and didn’t receive any college funding. I had inherited a small amount of money from my father when he died when I was 15, and I blew it on a car that quickly broke down. I attended a language camp that helped me pay rent briefly when I left home young, but by the time I landed in California at 19, I had almost nothing. I worked at a nearby pizza place — a great job because it was within walking distance — since I no longer owned a car and was riding BART to community college. That community college experience turned out to be wonderful, but I was counting every cent. Dinner most nights was cheap French toast made from store-bought bread, eggs, milk, and the cheapest syrup. It felt like a luxury compared to some of my childhood nights when we sometimes didn’t have dinner at all. My eating habits were ragged because of how I grew up. Back then I smoked cigarettes — a significant line item in my tiny budget — and I bought BART tickets and whatever clothes people left on the street. I had one coat and one pair of shoes, both tattered. I was broke.

The pizza job covered rent, tuition was inexpensive, and somehow I managed. I had to overfunction: work long hours, take lots of classes, and keep everything together. Surprisingly, being so highly functional felt exhilarating. I had a boyfriend then — at first supportive, later not — and I should have left as the relationship went downhill. When it fell apart, I ended up couch surfing for a summer, scraping together money and work. I picked up a job as a home health aide, which helped because I could eat there and do homework between shifts. My commute to school was ninety minutes on public transit, which actually gave me time to read and study.

This was before personal computers were common, and I had a beat-up typewriter I’d scavenged off the street — grossly, it had been used as a litter box and reeked of cat urine until I shook and rinsed it out. It always had grit in the keys, but with a single new ribbon I could make it work and type my papers. I’d draft longhand on the bus and streetcars, then type them up later — anyone my age remembers having to do that two-step process. I wrote well, which set a foundation for becoming an author later on. But pounding those keys through the remaining cat litter took a toll: I actually chipped a bone in my knuckle from striking so hard and woke up with a swollen finger. For the first time in my life, attending San Francisco State gave me health insurance; they x‑rayed the finger and splinted it. Having my dominant hand splinted was a nuisance, but I kept going.

I sustained that pace by smoking a lot and drinking buckets of coffee. I’ll tell you plainly: I eventually quit smoking — I quit at 34 and have stayed smoke-free for a long time — but back then nicotine was how I held myself together. It was an ugly, temporary form of regulation that seemed to work until its side effects didn’t. Some days I didn’t eat enough, and I carried a constant stomach ache; stress showed up in my body as chronic gastric pain. Even though that version of me wasn’t who I’d been earlier, the stress fueled my push forward. I earned excellent grades, graduated with honors, produced solid work, and became the first female producer at the small college cable station. Yet I was utterly frayed.

During that period I started performing comedy and did shows nightly. I was exhausted and could not sleep when given the chance because worry kept me wired. I was an overfunctioner — a pattern I see often as a particular form of female stress response. I’ve encountered men like this too, but being around that relentless energy now is difficult for me because it’s contagious; I feel fragile and can easily slip back into old patterns. In my current work — helping others heal from childhood wounds — I have to keep reminding myself that never-ending hustle isn’t healing. There will always be another video to make, another thumbnail to design, another course to launch, membership responsibilities, coaching sessions, staff to manage. It can be infinite, so a conscious boundary is necessary: pushing harder and harder does not equal more success; it reaches a point of diminishing returns. That pattern — relentless overwork to manage dysregulation — is one way trauma can manifest in women.

After graduation, a comedy trio I’d started with two others moved from San Francisco to Los Angeles to try for a foothold in Hollywood — a reasonable leap given our talent. San Francisco in the ’80s had a wild comedy scene that embraced the absurd, and we fit right in; skits didn’t need tidy endings or to make literal sense. We convinced comedy clubs to slot our written sketches into stand-up lineups, which was unconventional but worked. In my final college year I survived on no more than four hours’ sleep a night, made six dollars an hour as a home health aide, and still showed up as the star student — driven by a desperate need to be seen as “good” after growing up with an alcoholic mother. It was joyful and exhausting at once.

In LA I found temp work, including at a public TV station, but I couldn’t stop overdoing it. We worked forty-hour weeks, performed multiple shows each week, rehearsed any spare hour and weekend, and chased bookings. That’s how you try to succeed in Hollywood: constant output, no downtime. The social life, the hikes, the restaurants — none of it. In two and a half years I went to the beach twice. We were doing well, had an agent, and a respected comedian — Bud Friedman, who ran the Improv — told us that if we tightened our act with a director he would put us on the main lineup. That was a huge break. Then my trauma resurfaced in a physical way. I developed baffling symptoms: a persistent low-grade fever around 99–100°F that lasted nearly a year, dizziness triggered by bright lights, overwhelming fatigue — if I stayed up late, it felt as if a truck had hit me and weeks were required to recover. Doctors eventually diagnosed me with chronic fatigue syndrome, an emerging diagnosis at the time. It took a year to improve, which is fortunate because not everyone recovers.

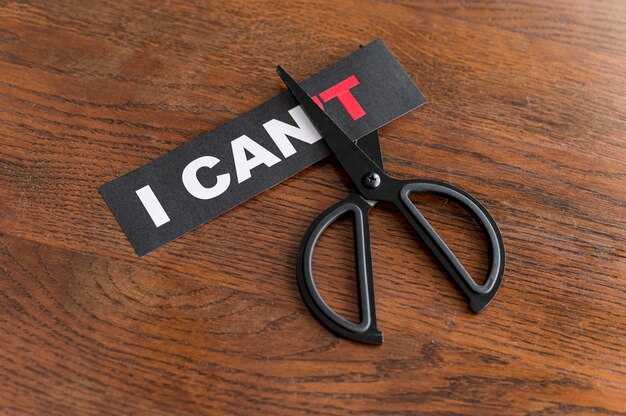

My recovery only began when I abandoned the apartment, walked away from the Hollywood dream, returned to the Bay Area, and took a low-stress administrative job to regroup. Over time I did a few small creative projects — a short humorous film that won a prize and a well-received self-help book — back in the ’90s. But though those efforts saw some success, I didn’t pursue the momentum. The LA experience left a wound: a loss of confidence and a two-decade silence in my creativity. It eventually came back, and now I’m in the work again, but that period illustrates a common pattern of untreated trauma in women. Underneath everything was dysregulation. I convinced myself I had failed at comedy and writing, when in truth trauma hijacked my capacity and forced me to shrink. That’s why, after small wins, I kept giving up. It explains why everything felt so hard and why I played small to control those symptoms. Have you ever held yourself down just to manage the chaos inside you?

When trauma happens, especially in childhood, your nervous system learns survival patterns. These are not moral failings; they are adaptations. Constantly scanning for threats, being triggered by silence, or shutting down emotionally when overwhelmed — these responses started as protection. They may no longer help you now, but they once kept you safe. So you’re not crazy; you’re dysregulated. For some people, frantic activity in quiet moments is a flashback; for others, it looks like anxiety. That chronic concern about how others view you — “Do they like me? What do they think?” — is a common, often female, manifestation of trauma rooted in inconsistent or conditional love. If you withdraw or numb out, that may have been the safest strategy when closeness felt risky.

Not every trauma looks the same, but if you recognize yourself in any of this, you are not alone. It helps to know the usual signs that your nervous system is still operating from past threats. I offer a free download that outlines the signs of dysregulation so you can see how many apply to you; I’ll link it in the first link in the description below this video — the dysregulation quiz. Stop telling yourself you’re overreacting. Reframe it as over-surviving: your system learned to keep you alive and now it needs retraining.

So what can you do when everything feels like too much? Here are three grounded actions you can try today to start shifting things. Sometimes healing begins with tiny acts; sometimes it requires bolder moves, like finally setting a boundary, ending a relationship, or walking away from what drains you. Change doesn’t wait until you “feel ready.” It starts the moment you stop tolerating what doesn’t work. When you keep accommodating and shrinking for bad situations, nothing changes. Stop tolerating it and the shift begins.

First: Catch the automatic “sorry” reflex and trade it for a single true sentence. Constantly apologizing — a frequent expression of female trauma — is often not politeness but a survival habit formed where love and safety were conditional. If you find yourself automatically saying “Sorry, I don’t know” when asked a question, try instead “Hm, I don’t know.” If you’re late and your instinct is to blurt, “Sorry, I’m so late,” try “Thanks for waiting.” Do you hear the difference? One is a shrink-to-fit apology; the other is an honest acknowledgment. Stopping the habitual “sorry” helps retrain your nervous system that you don’t need to make yourself small to keep connections. It actually lets you show up more honestly and with greater presence.

Second: Let go of one task that isn’t yours to carry. If your stress level is constantly high and you keep telling yourself you’re not doing enough, you may be overfunctioning. That behavior often develops when you never had space to tend to your own needs. You rush and take others’ responsibilities on. Today, choose one thing to stop doing that isn’t yours. For me it was nagging my son to make a phone call to a training program; I realized it was his call to make, so I told him I’d stop pressing him. He agreed, and it felt respectful for both of us. You don’t have to explain yourself or apologize — just let someone else take responsibility or allow something to remain undone. Try it with a household chore once and see that the world keeps turning. This simple act starts boundary-setting without a dramatic confrontation.

Third: Say one honest thing to someone who has earned your trust. If you’re hypersensitive to rejection, honesty can feel terrifying, as if it will lead to abandonment. Yet staying silent erases you over time. Practice speaking one small truth with someone who has shown warmth and reliability — not your distant boss, not a new acquaintance, but someone who sees you. Say something like, “Ouch, that hurt my feelings,” or “I could really use some support right now,” or even, “Hm, I don’t agree with that.” You don’t need to overexplain; a simple, honest expression can be enough. People accustomed to your silence may be surprised, and your honesty gives them data about who you are. It’s a small boundary and a step toward being known. Start with the easiest people and gradually practice in more vulnerable contexts. Speaking up is how you relearn the difference between threat — which your trauma expects — and closeness, which you actually want.

I also have a free download with friendship skills — things I didn’t learn at home — and it’s helpful to have a reference: What does a good friend do? How does a healthy friendship behave? I’ll put that in the second link down in the description and send it when you enter an email.

People who grew up in fear often learned to carry others’ emotions and neglect their own, to smooth things over, to avoid being a burden. When you begin to heal you might feel waves of guilt — like you should have been keeping everyone calm — and it can feel selfish to prioritize yourself. That’s trauma talking. Trauma can teach that self-protection is betrayal, that calm is unsafe, and that pain is the norm. So it’s understandable that trust feels difficult, that love prompts flight, that you find yourself drawn to people who don’t trust or treat you well — familiarity is powerful. Healing means learning a new normal: feeling safe around safe people, and starting with regulating your nervous system. Stop beating yourself up as if you’re a failure. We all make mistakes and are learning. You are resilient. Your emotions are not too much; you were asked to carry too much, too early. Wanting love is not a flaw — it shows you are alive inside.

You are already doing the most productive thing simply by healing. Every walk you take, every real meal you eat, every friend you stay connected with builds the capacity you needed all along. Real recovery is not about perfection or polish; it’s about honesty. You fall, get up, learn tools, and keep showing up on messy days. Messy is the new normal. If you’re tired of waiting to feel ready, start now. Start small and uncertain — the life you want is made from what you do today. You don’t have to remain stuck; change can begin with one small step.

If you like this video, there’s another one you’ll probably enjoy right here. I’ll see you soon. Dysregulation activates when stress and crises arrive; the noise of that stress feels like flooding — too loud and overwhelming.

Vous n'êtes pas fou(e) — voici à quoi ressemble le traumatisme féminin.">

Vous n'êtes pas fou(e) — voici à quoi ressemble le traumatisme féminin.">

Relationship EXPERT reveals Secrets to Connection: Dr. Sue Johnson">

Relationship EXPERT reveals Secrets to Connection: Dr. Sue Johnson">

Êtes-vous entouré de brutes ? La raison cachée pour laquelle vous les laissez entrer.">

Êtes-vous entouré de brutes ? La raison cachée pour laquelle vous les laissez entrer.">

Le comportement de votre partenaire est lié à un traumatisme, mais ce n'est toujours pas acceptable.">

Le comportement de votre partenaire est lié à un traumatisme, mais ce n'est toujours pas acceptable.">

The STRONGEST Sign An Avoidant Still Loves You Deeply">

The STRONGEST Sign An Avoidant Still Loves You Deeply">

If You Shut Down During Conflict, Watch This">

If You Shut Down During Conflict, Watch This">

If Your Partner Says These Phrases, They’re an Avoidant">

If Your Partner Says These Phrases, They’re an Avoidant">

Until This One Shift Finally Made the Avoidant Come Back | Mel Robbins Motivational Speech">

Until This One Shift Finally Made the Avoidant Come Back | Mel Robbins Motivational Speech">

For Healing, Sane Action is More Powerful Than Sad Stories">

For Healing, Sane Action is More Powerful Than Sad Stories">

A Partner Needs to Know About Your Past — But What If You’re Just Dating?">

A Partner Needs to Know About Your Past — But What If You’re Just Dating?">

CHEATING is for SELFISH COWARDS (like me)">

CHEATING is for SELFISH COWARDS (like me)">