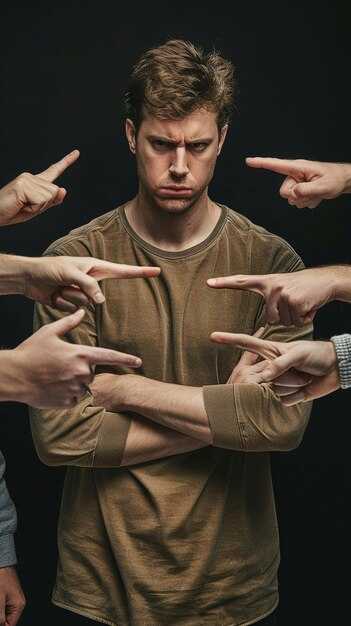

Have you ever ceased pursuing someone and noticed the atmosphere change? Ever wondered what goes through their head when you stop texting, stop waiting, stop investing emotionally—not as a tactic, but for real? There’s an old idea that we don’t truly lose someone until they stop occupying our thoughts—and that’s exactly where the real story often begins. If you’ve loved someone with an avoidant attachment style, you know this pattern intimately. One day they’re present, warm, even affectionate. The next day they withdraw with little or no explanation. Your instinct is to work harder: send another message, wait longer for a reply, contort yourself to win them back. But there’s a hidden dynamic around avoidance few people talk about. Avoidant partners don’t simply exit and erase you. They may run, but they often keep you in their mental orbit. When you genuinely stop pursuing them—when you unplug emotionally—it doesn’t only transform your experience. It sets off processes inside them, too. I’m not describing a manipulative “no-contact” trick you read online. I’m talking about the point where you’ve had enough, where you decide, “I can’t keep doing this.” You stop performing to earn their attention. You stop shrinking your needs to fit their comfort. You stop trying to prove your value. For an avoidant person, your withdrawal creates an unplanned void. They’re used to your consistent presence as a safety net: someone to retreat from and return to. Their emotional habits assume that you’ll be the one to reach first. When that pattern ends, it disturbs their rhythm, alters the power balance, and forces their nervous system to face something it’s been dodging—the risk of losing someone who made them feel safe, even if they wouldn’t admit it. Let’s walk through, step by step, what goes on in an avoidant mind when you stop chasing: from the initial euphoric relief to the creeping hollow, the nostalgic fog, the comeback attempts, and finally to the moment you reclaim your power for good. First, we must clarify who we mean by “avoidant.” If you’ve felt like you were loving someone with a foot already out the door, you were probably up against avoidant attachment. This isn’t about an inability to care or to love; it’s about how their nervous system handles closeness. Avoidant patterns often stem from early experiences where emotional intimacy felt unsafe, chaotic, or overwhelming—homes where vulnerability was ignored, criticized, or punished. Over time, a simple rule forms: getting close equals losing control; depending on someone risks hurt. As adults, these people still want connection. But when relationships deepen, their internal alarm system—centered in the amygdala—triggers, and their instinct is to pull away rather than lean in. They create distance to return to what feels safe: autonomy, self-sufficiency, control. Often this happens without clear awareness. They might explain it away—“I need space,” or “Work’s been a lot”—but the underlying motive is managing the anxiety intimacy brings. If you’re trying to love them, it can feel like embracing a shadow: warmth and closeness one moment, cold withdrawal the next. You begin to doubt yourself—did I say the wrong thing? Did I ask too much? Usually, you’ve simply reached the edge of their comfort. Important to remember: avoidant attachment is not irreversible. People can heal, but chasing, over-giving, or diminishing yourself isn’t the cure. Growth happens when both partners learn the wiring, respect boundaries, and commit to real work—separately and together. Once you recognize the pattern, you can choose whether to remain in the same role or step away. Phase One: the instant you stop chasing and the relationship ends, many avoidants experience what researchers call deactivation euphoria. Brutal as it may feel to hear, this initial reaction can look like indifference toward you. In the days or weeks after the split—especially if you were the one who leaned in while they leaned out—they feel a tremendous sense of relief. It’s not a condemnation of your worth; it’s their nervous system finally getting respite from the closeness that set off their alarms. Think of someone surfacing after holding their breath—the first gulp of air feels incredible. For them, that inhale is space. You’ll notice it outwardly: more social activity, upbeat posts, intense focus on work or friends, sometimes even a quick rebound. From the outside it may seem like they moved on overnight while you’re unraveling, but that’s a misleading picture. They’re in avoidance mode: dopamine and a false sense of freedom mask the reality that they’ve removed the source of emotional pressure. In this stage they often engage in selective recall—zooming in on moments they felt constrained or criticized and rehearsing those memories to justify leaving. But this high is temporary; it’s a defensive response, not genuine healing or closure. In roughly the first four weeks after you step back, they double down on distractions—new hobbies, new social circles, busier schedules—to avoid feeling the loss. If you break your detachment now and chase, you’ll simply restore the safety net and validate their belief that you’ll always be there when they want you. Your task in phase one is straightforward: protect your energy and keep boundaries firm, because phase two is coming. Phase Two: the quiet emptiness. As the euphoria fades, parties and packed calendars no longer provide the same rush. The freedom they once celebrated starts to level out and a low-grade loneliness creeps in. Avoidants rarely collapse into instant heartbreak; the absence shows up as a persistent, muted ache rather than a dramatic breakdown. They begin noticing small voids: nobody checking in about their day, no shared jokes over dinner, no one beside them on the couch for their favorite show. Even if they’d insisted those moments didn’t matter, their absence becomes felt. Often they won’t tie this feeling directly to you. Instead they search for external fixes—new hobbies, travel, more work—because admitting they miss you would mean touching vulnerability they’ve long avoided. So they keep filling the space: casual dates, extra projects, a busier social feed proclaiming “better than ever.” Yet in quiet hours, your absence registers—the steady presence you offered that balanced their emotional state is gone, and their nervous system notices the subtle drop. If you’re loosely connected, you may observe tentative signs—a like on an old post, a name mentioned by a mutual friend, the occasional text—small tests rather than full reconnection. This phase makes detachment difficult for you because those flickers can look like hope. But remember: their restlessness isn’t the same as readiness. If you go back to contact now, you interrupt a process that could force them to face the consequences of losing the safety you provided. Keep holding firm—the deeper longing is still ahead. Phase Three: nostalgia and phantom relationship syndrome. Typically between four and twelve months after you stop pursuing them, the distractions lose their potency and the quiet emptiness has lingered long enough to nudge memory in a new direction. Their thoughts begin drifting toward you. Human memory is biased to preserve pleasant moments, so they start to edit the past—downplaying the pressure and discomfort they felt and amplifying times they felt understood and accepted. This selective memory shapes an idealized, partial version of the relationship: the phantom where difficulties have been erased. That’s phantom relationship syndrome—missing not just you, but an edited, more flattering narrative of what you two had. You might see this when they reach out with a random nostalgic line—“Remember that trip?”—or when they watch your stories and don’t comment, or contact you on meaningful dates. Crucially, nostalgia is not the same as readiness. Longing for the comfort you gave doesn’t prove they can tolerate real intimacy now. In this phase they’re conflicted: the memory of safety pulls them close while long-standing fears of closeness pull them away. If you re-engage too quickly, you risk re-entering the same cycle—an approach of short-lived closeness followed by retreat when intimacy deepens. Stay grounded here: remember nostalgia often reflects missing a feeling, not embracing the whole, complicated person. Phase Four: the return attempts. Between roughly twelve and twenty-four months after you stopped chasing, some avoidant partners circle back. This is the most tempting—and most dangerous—moment if you’ve maintained your boundaries. The nostalgia that simmered in phase three can coalesce into action. Their longing can finally outweigh fear, creating a drive to reconnect. Contact may be tentative (“Hey, thinking of you.”), or direct (“I miss you. Can we talk?”), and sometimes it’s wrapped in what sounds like insight—statements of reflection and promises of change. But many return attempts stem from emotional hunger rather than true readiness. They want relief from loneliness and the gap you filled, not necessarily to do the hard work required to sustain intimacy. If you let them in without proof of lasting change, you risk reheating the same push-pull pattern: closeness, comfort, then withdrawal. Some avoidants do use this time as a turning point—therapy, improved emotional regulation, consistent work—so change is possible. Words alone aren’t enough. Look for sustained, measurable behaviors over time that align with their claims. When they show up now, keep calm and insist on specificity. Ask what steps they’ve taken to change, and preserve your boundaries: the door reopens only for consistent, respectful action. Phase Four forces a real decision—start anew or replay the old script. Phase Five: this phase focuses on you and the role you play in ending or perpetuating the loop. Your response to detaching is the single most influential factor in whether the pattern repeats. Many partners unknowingly keep the cycle alive. They let their guard down when the avoidant returns, skip the hard questions, and rush back in because the warmth feels like vindication. When that happens, the old dynamic reasserts itself quickly. True detachment is more than ignoring calls or deleting contacts. It’s a full reset of the relationship dynamic, beginning with how you see and value yourself. Practically, this means you stop being the automatic safety net. Detachment allows others to experience the consequences of their choices rather than you cushioning every fall. It requires clear boundaries and non-negotiables. Decide what behaviors you will no longer accept and define what respect looks like for you—if you don’t set these limits, you can’t enforce them. Keep your independence genuine and durable. Avoidants are attracted to partners who stand solidly on their own two feet; but that independence must persist even if they return. Maintain your social life, pursue personal interests, and reinforce financial and emotional autonomy so your wellbeing doesn’t hinge on their presence. Demand evidence, not promises. Anyone can say “I’ve changed,” but change is demonstrated through steady actions over time, not through a single emotional confession. Here’s the liberating truth: when you detach properly, you break their predictable pattern. You stop being the endlessly available person they can drift from and back to at will. That shift will feel uncomfortable for both of you—but discomfort is the gateway to real change, if change is possible. Protect that doorway. Not everyone who knocks deserves reentry. Sometimes the most compassionate choice—for yourself and for them—is to keep the door closed until real, consistent transformation appears. Now, practical steps: a specific action plan to stop the cycle, whether they return or not. Four pillars matter—miss any and you increase the chance of replaying the pain; practice them and you create room for genuine change, with or without the other person. Pillar One: boundaries that breathe, not bend. Boundaries are not walls but controlled doorways—you decide who enters and on what terms. That could mean saying, “If you disappear for weeks, that’s unacceptable to me,” or “Reconnect only if you’re consistent and respectful.” Boundaries only work when you enforce them. If you collapse them the moment emotions spike, you teach yourself and the avoidant that limits are optional. Pillar Two: no-contact with purpose. This isn’t punitive silence; it’s deliberate space for both people to process the breakup. For you, it’s a time to heal, regain clarity, and rebuild your emotional center. For them, it’s an opportunity to feel the true absence of your support. Set a timeframe—30, 60 days, or whatever you need—and use that period to focus on yourself, not as a calendar to wait by the phone. Pillar Three: independence as a lifestyle. Avoidants are attracted to grounded partners, but you must maintain that groundedness even if they return. Cultivate friendships, hobbies, and financial/emotional resilience that do not depend on them. When your happiness comes from within, you make wiser decisions about whether they belong in your future. Pillar Four: require actions, not declarations. This is the filter that shields you from false starts. If they claim to have changed, look for concrete signs: consistent initiation, conflict-handling without disappearance, the ability to talk about fear rather than shut down. If these behaviors aren’t present, it’s likely temporary comfort-seeking, not real transformation. Taking the wheel back is your work. The good news: follow this plan and you win either way. If they rise to meet your standards, any future together will be healthier. If they cannot, you’ve already built a life that preserves your dignity and allows you to walk away whole. To close: remember, you are not someone’s emotional halfway house or a rest stop for when they’re tired of fleeing themselves. You’re not here to facilitate the repetition of a pattern that breaks your heart. When you detach—fully—you’re not punishing anyone. You are protecting yourself. You’re declaring, “My peace matters. My life matters.” That stance isn’t selfish; it’s healthy. Don’t measure your worth by whether they return. Their comeback isn’t proof you’ve won, and their absence doesn’t mean you’ve lost. The real victory is preserving your self-respect, regardless of their choice. People can change, but only if they genuinely want to and are willing to do the often uncomfortable, consistent work to rewire their patterns—that’s not your responsibility. Your responsibility is to decide, based on their actions, whether they match the love and life you deserve. If not, close that chapter—not bitterly, not vindictively, simply done. Peace trumps chaos; self-respect trumps false hope. Finally, remember: detachment is not the end of your love story; it’s the beginning of one where you are the main character. You don’t beg for a role in someone else’s life when you’re fully engaged in your own. If you stand at this crossroads wondering whether to keep waiting, ask yourself: if nothing changes, can I still be okay where I am? If the answer is no, let go, enforce your boundary, and move toward a life that feels good from the inside out. That’s how the cycle ends and how you reclaim peace. If this message resonated, pass it along to someone who needs to hear it. Many people are stuck in the same pattern, thinking they’re alone—your share could help them see the loop and take their power back. And if you’re ready, commit to the boundaries you need today. You are not anyone’s backup plan. You are the central figure in your own life—keep showing up for yourself, protect your boundaries, and live fully.

What Really Happens to Avoidants After a Breakup And Why They Come Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

What Really Happens to Avoidants After a Breakup And Why They Come Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

ISSO PROVA que um EVITATIVO Quer Você PARA SEMPRE (e Ama Você Profundamente)">

ISSO PROVA que um EVITATIVO Quer Você PARA SEMPRE (e Ama Você Profundamente)">

Por que o seu eu traumatizado ANSEIA POR ORDEM">

Por que o seu eu traumatizado ANSEIA POR ORDEM">

As 5 Regras Não Ditas Para Fazer um Homem Evitativo Finalmente Desejar uma Conexão Profunda">

As 5 Regras Não Ditas Para Fazer um Homem Evitativo Finalmente Desejar uma Conexão Profunda">

">

">

Eu descobri por que meus Relacionamentos continuavam Falhando.">

Eu descobri por que meus Relacionamentos continuavam Falhando.">

As Fronteiras funcionam com Narcisistas?">

As Fronteiras funcionam com Narcisistas?">

Dicas Para Recuperar MAIS RAPIDAMENTE Dos Efeitos do Trauma (Compilação de 4 Vídeos)">

Dicas Para Recuperar MAIS RAPIDAMENTE Dos Efeitos do Trauma (Compilação de 4 Vídeos)">

A pornografia é EXTREMAMENTE perigosa para a sua Relação.">

A pornografia é EXTREMAMENTE perigosa para a sua Relação.">

Este ÚNICO Truque de Carinho Cria Laços Inquebráveis com Personalidades Evitantes">

Este ÚNICO Truque de Carinho Cria Laços Inquebráveis com Personalidades Evitantes">