Focus on the eyes first: watch eyelids for widening or narrowing, check whether the inner-brow lifts, and note if the mouth goes open – those signals distinguish surprise, fear and calm, and they reveal anxiety when paired with shallow breaths or tightened lips.

Combine cues to increase accuracy: a distinctive inner-brow raise with downturned mouth corners usually signals sadness, while inner-brow lift plus tight eyelids and lip retraction points toward anxiety or fear. Compare each cue to the same person’s neutral face rather than guessing from a single instant, and step back when one cue appears without supporting signs.

Train with concrete materials: read recommended books and source articles, and study how ekmans used the Facial Action Coding System to label muscle actions. Watch interviews frame-by-frame to catch microexpressions (they often fade under 0.5 seconds), log cases, and mark side glances and brief eyelids shifts for pattern analysis.

Apply a simple habit: establish a back baseline for each person and score deviations for clearer understanding. Don’t read much into a fleeting look; instead tally patterns across conversations and cases, and keep in mind cultural differences that change how facial cues present.

Use this quick checklist when you practice: note eyelids (open vs narrowed), brow AUs (inner-brow vs outer), mouth openness, symmetry and side glances; review interviews and real interactions until distinctive facial combinations register automatically in your mind.

Practical step-by-step method to decode facial expressions in real interactions

Step 1: Watch the eyes first – monitor eyelids, gaze direction and micro-movements to read the initial signal; an authentic change appears in the eyes before the rest of the face.

Step 2: Track mouth opening and pulling of lip corners; a brief, asymmetric pull is likely a controlled smile that often lies about true feeling, while a symmetric movement aligns with what you hear.

Step 3: Time reactions: measure the whole-face onset and a second reaction. Genuine expressions rise and decay in about 200–500 ms, and a delayed second movement suggests executive control rather than spontaneous emotion.

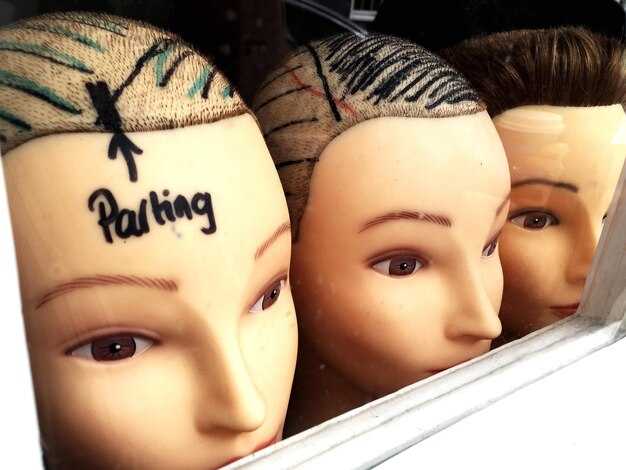

Step 4: Create a baseline with a photograph or short video of the person in a neutral moment, then make quick updates after short interactions; compare loss of eye contact, raise of brow or changes in posture to that baseline.

Step 5: Use situational cues: ask a fact question and watch for silent micro-expressions during the pause – themselves reveal mismatch between words and feelings and give something concrete to analyze.

Step 6: Adjust for role and context: in executive meetings people usually mask stress; treat the interaction like a therapist would, not like meeting an enemy, so you avoid bias and can more readily believe consistent facial movements.

Step 7: Score reliability: record 15‑second clips, note frequency of initial micro-expressions, count second corrections, and assign a 1–5 trust score; focus on patterns rather than single frames to reduce false positives.

Scan facial zones in order: brows → eyes → nose → mouth to gather cue sequence

Scan the brows first for 1–2 segundos, the eyes next for 2–3 seconds, the nose briefly for 0.5–1 second, and finish at the mouth for 1–2 segundos; record the order and the changes you see so you capture the cue sequence reliably.

Watch the fore area (brows and forehead) for drawn or raised positions: corrugator activation produces a vertical pull between brows, frontalis lifts brows. Those muscle patterns give immediate information about surprise, concentration or anger and set context for corresponding eye cues. Note asymmetry and how long a change lasts – micro shifts under one second often reveal brief felt reactions.

Observe the eyes across two layers: the gaze/attention direction and the periocular muscles. Orbicularis oculi contraction (crow’s feet) plus cheek lift usually signals a genuine smile; absence of eye engagement when the mouth smiles may indicate polite affect or lies. Track whether the whites of the eyes widen or constrict, because those movements change interpretation of brows and mouth.

Check the nose for flaring, wrinkling or subtle sniffing; levator labii action near the nose signals disgust, while flared nostrils point toward arousal or irritation. Use this quick nose check as a tie-breaker when brows and eyes give mixed signals – the nose often shifts before the mouth completes a full expression.

Finish at the mouth and compare its position to earlier zones: lip corner raise with orbicularis oculi tells you contentment or genuine happiness, lip compression or tight lips paired with drawn brows suggest tension or withheld words, and parted lips with downward gaze can indicate uncertainty or that someone wants to speak. Treat the mouth both as an expressive zone and a performance cue – people modify mouth expressions themselves to manage impressions.

Practice deliberately: record short clips and score your reads over 50 examples, timing each zone with a stopwatch, and note corresponding muscles and seconds of activation. Train with a guinea volunteer or role-play partner, alternating roles so they can feel the effect of their expressions themselves and you get well-calibrated feedback. Compare accuracy across peoples and contexts, log whether mistakes cluster because of cultural differences, and refine your technique allowing small adjustments that improve real-world performance.

Detect micro-expressions: timing windows, rapid muscle twitches, and eye movement signs

Limit observation windows to 40–200 ms (1/25–1/5 second) and scan faces in 40 ms slices; this lets you catch micro-expressions that disappear before a full second. Practice on slowed 0.1x clips, then test at real time: pause frame-by-frame when you spot a twitch in the eyelids, brow, or mouth.

Watch specific muscles: orbicularis oculi (crow’s feet) signals genuine smiles, zygomaticus major pulls lips up, corrugator supercilii tightens brows for anger or concentration, and levator labii exposes disgust. Rapid muscle twitches that last under 200 ms and involve two or more muscle groups often indicate mixed emotion; a short cheek twitch paired with brow movement can mean conflict between felt and expressed state.

Use the eyes as primary anchors: micro-saccades, brief gaze shifts, asymmetric eyelids movement, and blink rate spikes carry reliable cues. Pupil change is informative but requires controlled light or instrumentation. Notice when eyes briefly avert and then return to a speaker – that silent rebound often signals concealed discomfort. On first look you may miss these signs because they are fleeting; slowing video and stepping through frames shows the exact frame where the cue is shown.

Adopt a simple drill: collect 60 short clips (1–3 s) on a training website, label perceived emotion within 2 s, then compare against expert annotations. If you struggle, reduce clip count and increase feedback frequency until accuracy improves 10–15% per week. Cuncic and other western trainers have published modules and video content that pair examples with explanatory information; review those modules and repeat until patterns become learned rather than theoretical.

Apply rules in conversation: look for mismatches between mouth and eyes, prioritize muscles around the eyes over speech, and pause before reacting so you observe whether the micro-expression rebounds or fades. Therapy approaches supported by micro-expression work can reduce miscommunication and loss of rapport when practitioners use targeted practice; suggest integrating short daily drills into clinical or coaching sessions.

Track progress quantitatively: record baseline accuracy, log changes after 2 weeks of training, and keep brief notes on which cues you miss most. Share anonymized video examples with peers for critique; others will spot the small eyelid or brow twitches you overlooked. Use this routine because repeated, focused exposure converts sporadic recognition into reliable skill without long, unfocused study.

Apply FACS action units: read specific AU combos that indicate anger, sadness, surprise, joy

First, read AUs in this order: brows, eyes, nose/cheeks, mouth – then confirm with timing, symmetry and context.

-

Anger – common AU combo

- AU4 (brow lowerer) + AU7 (lid tightener) + AU23/24 (lip tightener/pressor).

- Look for hard, downward pull of brows and visible tension around the eyes and mouth; the expression often looks constricted because muscles around the mouth move inward.

- Involuntary anger microexpressions last very briefly (~40–200 ms) but deliberate anger persists with sustained AU4 and jaw tension.

- Actors can learn to simulate AU23/24 without AU7; genuine anger typically includes eye tension that is harder to fake.

-

Sadness – common AU combo

- AU1+4 (inner brow raiser + brow lowerer triangle) + AU15 (lip corner depressor).

- Recognize a raised inner brow that makes the eyes appear mournful and corners of the mouth dropping; this combination often occurs with slow onset and longer duration.

- Sadness can be mixed with other AUs (e.g., AU1+4 with AU12) – check social background and triggers to distinguish layered emotions.

-

Surprise – common AU combo

- AU1+2 (inner and outer brow raisers) + AU5 (upper lid raiser) + AU26 (jaw drop) or AU27 (mouth stretch).

- Expect a very quick onset and short duration; eyes open wide and brows lift high, producing a universally recognizable shape.

- Because surprise is frequently involuntary, timing is a strong authenticity cue: sudden onset, brief peak, rapid resolution.

-

Joy (smile) – common AU combo

- AU12 (lip corner puller) + AU6 (cheek raiser) = Duchenne (genuine) smile.

- AU12 alone often signals a learned or polite smile; AU6 produces crow’s feet and eye narrowing that support authenticity.

- Measure duration and symmetry: genuine smiles show gradual onset, moderate duration, bilateral AU6 activation, and smooth offset.

Use these practical checks for all emotions:

- Timing: microexpressions are brief; sustained AUs suggest deliberate expression.

- Symmetry: asymmetric AUs can indicate suppressed emotion or mixed affect; mixed AU patterns often reflect competing feelings.

- Sequence: expressions often begin in brows/eyes then move to mouth; check whether AUs appear in that order.

- Context: match facial data with background and social triggers because the same AU combo can mean different things for different persons.

Practice and support: use evidence-based online FACS training and slow-motion video of various persons, then annotate AUs yourself. Try easy drills: mark AU onset, peak, offset; compare your labels to labeled datasets to become faster and more accurate. Keep mind of universality and learned displays–some expressions are universal while others are culturally learned–so combine AU reading with situational information rather than relying on AUs alone.

If you want a quick checklist for live observation, print a one-page card with AU numbers for anger (4,7,23/24), sadness (1,4,15), surprise (1,2,5,26), joy (6,12), then review recordings and ask yourself: was the movement involuntary, how long it occurred, and did it match the trigger? That approach gives evidence-based, repeatable support as you learn to read faces instead of guessing.

Establish a personal baseline and situational context to separate emotion from habit

Record three 60‑second silent videos of yourself in low‑stakes moments (reading, waiting, listening) and label each clip by situation; include one clip after a small loss (a little setback) and one when you feel content so you capture tightening, eyelids behavior and head posture across scenarios.

Use a simple coding sheet to identify normal ranges: note micro‑movements, typical blink rate, baseline eyebrow position and mouth openness. Apply the same labels across clips so you can compare: frequency, duration in seconds, direction of head tilt, opening of the mouth, and areas around the eyes. Keep entries in a workbook with time stamps and a short note about the situational trigger.

| Face area | Normal movement | Frequency/min | Typical duration (s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eyebrows | resting/raise | 2–6 | 0.2–1.2 | raise for surprise; sustained furrow suggests cognitive load |

| Eyelids | blinks, small droop | 8–20 | 0.1–0.3 | tightening around eyelids often precedes anger or pain |

| Mouth/jaw | smile compression, jaw set | variável | 0.5–2 | lip tightening can mask other emotions; lies rarely appear alone |

| Head/neck | tilt, forward/back | 1–4 | 0.5–3 | head pulled back plus narrowed eyes = distancing in that situation |

Compare someone’s current expression to your baseline immediately: if a motion exceeds your baseline by a clear margin – for example, eyelids dropping for more than two seconds or sudden jaw tightening – flag it as an emotional deviation. Use proven coding labels (neutral, approach, avoid, tension) and mark ambiguous cases for review; groups that train without objective coding often struggle to identify small cues.

Train with a volunteer (label them “guinea”) and rotate roles: one person acts as observer with the workbook while another acts out various prompts. Apply simple theory: brief spikes under two seconds are likely spontaneous emotional responses; longer holds often reflect control, habit or a practiced opening of an expression. Note where the behavior repeats in different situations to separate habit from genuine emotional change.

When you analyze, look for clusters of cues rather than a single sign: tightening around the eyes plus a fixed stare suggests anger, while a slight smile with relaxed eyelids indicates content. If you must infer deceptive behavior or lies, require multiple converging signals and situational evidence before you conclude anything. Use the workbook to chart trends over sessions and to understand how the same person reacts across various situations and emotional triggers; reference quick notes from the Daskal training method for additional drills that are proven to improve accuracy.

Choose a response: short verbal phrases and matching nonverbal moves for five common emotions

Use concise scripts and matching moves: practice one short phrase and one clear nonverbal for each emotion, film 5–10 repetitions, then adjust based on how your breath, eyes and face register.

Happiness – Phrase: “I’m glad you’re here.” Nonverbal: genuine smile that engages the orbicularis oculi muscle (soft crow’s-feet), gentle head nod, steady eye contact while looking at the person, exhale slowly; hold the expression over 1–3 seconds. Researchers suggest Duchenne activation signals sincerity; most people respond well to a smile that reaches the eyes.

Sadness – Phrase: “I’m sorry you’re feeling that.” Nonverbal: soften the brow, lower the gaze slightly, tilt the head to the side, keep shoulders relaxed, take a calm, slightly longer in-and-out breath and allow a silent two-second pause before you speak again; this acknowledges feelings without rushing the other person. People might lean in a little; avoid exaggerated pulling of facial muscles that look theatrical.

Anger – Phrase: “Help me understand what happened.” Nonverbal: neutralize tightened jaw and avoid pulling the lips into a thin line, keep palms visible and open at your side, steady your breathing (slow 4-count inhale, 6-count exhale), maintain level eye contact but relax the forehead muscles. A measured tone and controlled posture reduce escalation and mean you focus on the situation, not confrontation.

Fear – Phrase: “We can take one step at a time.” Nonverbal: soften wide eyes by lowering the upper lids slightly, avoid rapid backward recoil, keep shoulders un-hunched, place one open hand near your chest or at your side, slow the quick breath pattern where possible. Microexpressions of fear can occur in 0.04–0.2 seconds, so pause briefly to let the other person regain composure before continuing.

Surprise – Phrase: “Oh – really?” Nonverbal: raise arched eyebrows, open the mouth just a little on an intake of breath, quick head tilt, then return to a composed expression within 0.2–2 seconds; follow with clarifying eye contact. A brief silent reaction offers curiosity without judgement.

Practice & context notes: film yourself and compare against peers or the research community examples; western groups often rely on facial cues more than some other groups, so check for cultural variation before assuming meaning. If you ever feel unsure, ask a short follow-up question rather than guessing. Communication masters train timing (how long a face holds an emotion) and matching muscle activation; use small adjustments, not theatrical changes, and test responses in different social situations to see what works for people or something else you want to convey.

How to Read Facial Expressions – Step-by-Step Guide">

How to Read Facial Expressions – Step-by-Step Guide">

Short-Term Relationship Breakup – Why It Hurts & How to Heal">

Short-Term Relationship Breakup – Why It Hurts & How to Heal">

Is He Interested? Decoding the Signs of Romantic Interest">

Is He Interested? Decoding the Signs of Romantic Interest">

What Is the Point of Life? Why You Might Feel This Way and How to Find Meaning">

What Is the Point of Life? Why You Might Feel This Way and How to Find Meaning">

The Importance of Family Love – Strengthening Bonds & Wellbeing">

The Importance of Family Love – Strengthening Bonds & Wellbeing">

I Don’t Know Who I Am — How to Reconnect with Your True Self & Discover What You Want">

I Don’t Know Who I Am — How to Reconnect with Your True Self & Discover What You Want">

How to Stop Playing Mind Games While Dating — Practical Tips for Honest Relationships">

How to Stop Playing Mind Games While Dating — Practical Tips for Honest Relationships">

What Determines Sexual Attraction Exactly — Science, Psychology & Key Factors">

What Determines Sexual Attraction Exactly — Science, Psychology & Key Factors">

What Is Emotional Lability? Causes, Symptoms & Treatment">

What Is Emotional Lability? Causes, Symptoms & Treatment">

Happy Hormones – The Endocrine System and Brain Connection for Better Mood">

Happy Hormones – The Endocrine System and Brain Connection for Better Mood">

How Many Types of Love Are There? 9 Types Explained">

How Many Types of Love Are There? 9 Types Explained">