Being in company can feel overwhelming and activating, especially if you grew up with trauma — people can be harsh, judgmental, and make you feel excluded or like you don’t fit in. For many, those dynamics began at home during childhood. The survival strategy that developed for some was to shrink themselves, to hide who they really are. Below is an edited archive segment that walks through more than forty ways this kind of self-suppression shows up; these behaviors are extremely common, and if they keep happening they will limit your life. Grab something to take notes with while you read, because undoing these patterns is what leads to freedom.

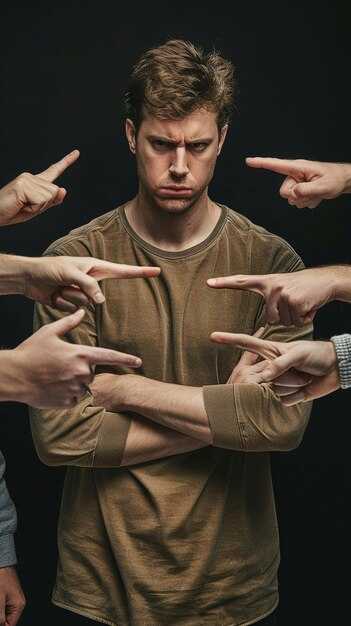

Some children who endured heavy criticism or bullying learn to stay invisible: don’t challenge the abuser, don’t try to achieve, don’t draw attention, don’t admit mistakes — the thinking being that staying small keeps you safe. That may have been true then, but if that strategy persists into adult life it becomes a pattern of avoidance — avoiding connection, achievement, meeting basic needs, and building a life that brings joy. Avoidance narrows life and breeds loneliness; it can feel as if an external force prevents change, and believing that makes people feel helpless, bitter, and angry. You may recognize people who preemptively defend themselves with anger and blame because they’re convinced nobody will ever understand or accept them. A bit of that tendency to hide, criticize, or blame others lives in most of us as a defense against feelings of unworthiness and isolation, but when it becomes a resentful martyr posture it pushes others away and damages relationships and opportunities. It’s useful to check in with yourself occasionally to see whether, beneath the surface, you are blocking your own path.

To help with that, here is a list of common signs that you may be enacting an old, unhealthy pattern of keeping your life small — a pattern that undermines happiness. First, there is material self-suppression: ways people diminish themselves materially. Number one: you mistake “living simply” for neglecting your needs; you may feel superiority for not owning comfortable or decent things and even feel resentful toward people who do. Number two: your home is cluttered and unclean — having a chaotic space reduces your capacity to invite people in, to imagine, and to think clearly; for people with complex PTSD, clutter can worsen dysregulation. Number three: you avoid exercise despite knowing how effective it is for depression, anxiety, and overall regulation; skipping movement keeps you from flourishing. Number four: you go to bed worrying and feeling guilty about what you ate, which signals a recurring pattern of eating against your intentions and keeps you stuck in shame instead of clear, empowering thinking. Number five: you postpone buying decent clothes until you reach a hypothetical future weight, filling your closet with multiple sizes and nothing that makes you feel presentable right now. Number six: your car is strewn with trash — like a messy home, a littered vehicle communicates a lack of care and can be a sign you’re not inviting people into your life; clean it out and it becomes easier to offer rides and connection. Number seven: your desk is a disaster; for those who work at a desk, clutter interferes with productivity and clarity — having a system to sort projects and keep the immediate workspace small helps creativity and calm. Number eight: you don’t allow yourself clothing that flatters you, whether out of future-weight expectations or low worth; even secondhand or thrifted finds can be a way to dress well now. Number nine: your underwear and bras are worn-out or stained — neglecting basics sends a message to yourself that you don’t deserve small comforts; there are affordable places to replace them and care for yourself.

Romantic self-suppression is another category. For example, you stay with someone who mistreats you and say nothing because any conflict feels unbearable. At some point in healing, you’ll need to speak up; honesty may unravel an unhealthy relationship, and if truth causes a relationship to end, it likely wasn’t solid anyway. Another form: you love someone and never admit it — sometimes fear of scaring them off is real (or they’re already attached to someone else), but concealing your feelings keeps the story stuck; revealing them may allow life to move on, one way or another. Spending time with someone who doesn’t reciprocate your affection is another way of shrinking — investing your capacity for love into a relationship that gives nothing back wastes your chance to be loved in return. Dating someone for years without committing because you prefer limbo is also keeping things small; if the relationship can’t become what you want, letting it go opens space for something better. Likewise, having a devoted partner while being unfaithful prevents genuine intimacy and ties up someone else’s emotional life to keep yourself safe; dishonesty never leads to good outcomes. Another common pattern is wanting a relationship but not taking any steps to find one — for people with complex PTSD, putting yourself out there can trigger intense grief, anxiety, and rage when rejection or perceived abandonment occurs. That intense reaction is sometimes called “abandonment mange” — a wave of grief, anxiety, and fury that can feel catastrophic. Naming it makes it easier to manage; when you understand what it is, you can tolerate the feelings and still take risks, like expressing interest in somebody who may not reciprocate. Strengthening your capacity to handle strong emotions is crucial for this work.

There are social signs of self-suppression too. You might claim you want friends but publicly assert that people are awful these days — sweeping cynicism (“people suck,” “all women want money,” “all men want sex”) is often trauma-driven thinking. If you genuinely want friends or romantic connection, that kind of blanket pessimism needs attention so you can be open to new possibilities. Another sign: you never host people; perhaps you’ll go to others’ homes but never invite them into yours. Or you complain and gossip about a friend instead of addressing issues directly with them — venting without seeking resolution damages relationships and someone’s reputation. You neglect simple gestures like sending birthday wishes; digital reminders like Facebook make it easy to reach out, and small consistent acts of care accumulate into meaningful friendships. A story: someone kept a Rolodex of birthdays and important events and used it to check in regularly; that practice filled their life with friends and joy late in life — it’s never too late to be that kind of person.

Small courtesies also matter: when you pass someone on the street, avoid staring at the ground; a brief hello or nod brightens both your day and theirs and costs almost nothing. If you avoid leaving the house because you worry about running into chatty neighbors, practice short exit lines (“So nice to see you — I have to run, take care!”) so you can greet people without getting swallowed into long interactions. If you love people but don’t call them, or you let the phone ring and don’t pick up out of fear that a conversation will be too much — those are ways of shrinking. Even small acts like patting a friendly dog that approaches show you can receive spontaneous affection; ignore the animal and you’re also ignoring a tiny offer of connection.

Another pattern is not participating when involvement is called for: you join groups but bail when things get awkward, then badmouth the group instead of leaving respectfully; burning bridges and speaking poorly of others usually isn’t necessary. At gatherings you bring the cheapest contribution or nothing at all and don’t help clean up — participation builds community and being generous helps you be invited back. In contexts like 12-step meetings, attending without doing the work (the steps) results in stagnation: recovery depends on action, not only complaining. Meetings where everyone only talks about how terrible life is can be demoralizing; in contrast, sharing what tools and steps help is powerful for newcomers and long-timers alike. If you’re in recovery or working on yourself, talk about solutions and the practices that help you; those stories are medicine for the community.

When it comes to achievement, self-suppression shows up in stories you tell to justify why you didn’t succeed — narratives that the world or other people blocked you. That’s a common trap: feeling that the deck is stacked, blaming bosses, partners, or friends, and using those stories to avoid taking responsibility for change. Taking back your sovereignty means acknowledging what you can do: if a situation is intolerable, it’s on you to act rather than waiting for a savior. Wanting a promotion but not acquiring the skills needed is a frequent example; investing in learning and showing up with professionalism can change outcomes. Of course economic systems have limits, but you do have agency to change your actions and improve your circumstances. When it became necessary to raise income, many people — often single parents — discover how quickly they can learn, shift habits, and negotiate for better pay; urgency can force growth, but it’s better to act earlier.

Screens are another subtle way people keep themselves small: spending every spare moment on phones, computers, streaming, or games eats time that could be used for positive change. Screens are useful for work and relaxation, but if they fill every hour they prevent personal development. The internet also provides countless free resources, and not spending time learning available knowledge is a missed opportunity. For example, after the 2008–2009 market collapse, some people taught themselves digital video editing and built new careers; acquiring practical skills opens doors. Living trapped by debt can also limit choices: sometimes debt functions like a self-imposed constraint that keeps options closed. Either accept current limitations and enjoy life anyway, or take practical steps to eliminate the obstacles so you can move forward.

Neglecting health is another clear form of self-suppression: skipping regular medical checkups or dental cleanings is concrete self-neglect that can cause serious problems. Then there is suppression of joy and growth. A living space with no art or plants, no beauty or personal touches, signals not investing in a life that feels worth living. Even if art isn’t your thing, find your version of a cared-for environment — proper furniture, utensils, and clean clothing are all ways of treating yourself like an adult who deserves comfort. Wanting a pet but not getting one is a form of delaying happiness; sometimes practical constraints make waiting necessary, but tending to desires for companionship is part of honoring yourself. Feeling mildly resentful or ashamed around people who seem to have things together is very common — shame and comparison push us away from people who are okay, and envy can lead to self-isolation instead of connection. Regretting friendships lost because of envy or resentment is a real loss; noticing that tendency allows you to work through it.

If any of these patterns ring true for you, the antidote is to begin expressing who you are. That’s complicated when abuse and neglect shaped you; being yourself can feel risky because old reflexes — prickliness, emotional dysregulation, or lashing out — still surface under stress. “Being yourself” is not license to act impulsively; it’s a process of becoming, where authentic expression is balanced by values like consideration, restraint, and strategy. Ask yourself whether snapping at a driver is actually necessary to be authentic, or whether your “real self” also includes patience and healthy stress-management tools so anger doesn’t harden into a harmful habit. Healing involves increasing self-awareness and practicing balanced self-expression.

Many people with complex PTSD struggle to name what they truly want because the question triggers grief and anxiety — “I’ll never get it anyway.” Still, clarifying desires, even vaguely at first, is important: write down wild dreams and let them evolve. Express yourself in how you appear, in what you say, and in the person you become; that is what healing looks like. Expect awkward moments and mistakes — blurting something or fearing you look foolish is part of the process. Healing proceeds by small experiments: fumbling, failing, learning, and trying again. If fear of criticism launched a lifetime of hiding, rebuilding requires support and persistence. Tools — books, videos, courses — plus human support from friends, groups, or recovery communities help enormously. If you’re inclined to isolate, note that gradual exposure to people practicing the same work is both gentle and necessary; without it, self-suppression tends to reassert itself.

If you want an approachable first step for handling the feelings that surface when you expand your comfort zone, try a daily practice that clears stuck thoughts and creates space for new, helpful ideas. Small daily techniques can be like opening a window in a stuffy room: they let stale thoughts out and allow fresh ones in, sometimes sparking a next-step idea or an inspiration. That kind of daily practice can be learned quickly — in under an hour — and there’s a free course available that teaches it. Click to sign up and begin; small, steady steps add up, and change is possible.

Perché Ti Nascondi la Tua Vera Identità (e 40 Modi per Liberartene)">

Perché Ti Nascondi la Tua Vera Identità (e 40 Modi per Liberartene)">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

THIS PROVES an AVOIDANT Wants You FOREVER (and Loves You Deeply)">

THIS PROVES an AVOIDANT Wants You FOREVER (and Loves You Deeply)">

Perché il tuo io traumatizzato HA BISOGNO DI ORDINE">

Perché il tuo io traumatizzato HA BISOGNO DI ORDINE">

Le 5 regole non scritte per far sì che un uomo evitante desideri ardentemente una connessione profonda">

Le 5 regole non scritte per far sì che un uomo evitante desideri ardentemente una connessione profonda">

">

">

I figured out why my Relationships kept Failing.">

I figured out why my Relationships kept Failing.">

Do Boundaries work on Narcissists">

Do Boundaries work on Narcissists">

Tips to Heal FASTER From Effects of Trauma (4-Video Compilation)">

Tips to Heal FASTER From Effects of Trauma (4-Video Compilation)">

Pornography is EXTREMELY dangerous to your Relationship">

Pornography is EXTREMELY dangerous to your Relationship">

This ONE Affection Hack Creates Unbreakable Bonds with Avoidants">

This ONE Affection Hack Creates Unbreakable Bonds with Avoidants">