Want to know why people sometimes recoil from you, tune out what you say, or get irritated before you even speak? It’s not because there’s something inherently wrong with you — it’s often because, at some point, you were taught not to use your voice. Either you weren’t really allowed to speak, or when you did speak nobody paid attention. As a child, your family shapes what feels normal. If your parents made room for your words, listened with curiosity, helped you shape your thoughts and encouraged you to speak clearly, you learned to trust your voice and to say what you meant. But if the opposite happened — if you were ignored, cut off, ridiculed, constantly corrected or spoken over — you didn’t learn that. You learned to feel anxious whenever you opened your mouth. You learned to dread expressing yourself and to expect rejection. That anxiety doesn’t vanish when you become an adult; it rewires you. You may find yourself talking too fast — do you? — filling every silence, over-explaining and over-justifying because you’re afraid of what will happen if you don’t. You feel like you have only a second to make your point before someone interrupts, so you rush, you raise your voice, and it comes out awkward. That usually makes people tune out more and confirms the fear that you’re “too much.” Have you heard that about yourself? I used to be told, “You’re too much, Anna. Slow down — you have so many ideas.” Or, “You don’t understand; your words don’t matter.” The problem isn’t that you’re excessive — it’s that you never practiced being allowed to speak calmly and trust someone to wait and listen.

I’ve worked on this with my younger son: he often starts sentences and then stops mid-thought. During lockdown we walked every day and when I asked him about his life he would begin to talk and then leave the sentence hanging. If I simply said, “Go on, I’m listening,” and waited, he would finish, and over time that made a real difference. He’s articulate now, but school had trained him to be timid and he hadn’t had much practice turning thoughts into words. Your nervous system can stay on high alert, braced for rejection; you hedge everything you say with “Um, well, maybe it’s just me,” or “This might sound weird, but…,” shrinking before you begin. And when others see someone step back like that, they unconsciously follow suit: they mirror your low-energy cues, assume you’re low status or unworthy of attention, and don’t give you the space to finish.

Sometimes the opposite happens: you swing the other way, get loud, dominate conversations, interrupt — not out of rudeness but from panic at being ignored. It feels like survival to be heard, an old childhood urgency that leaks out now. That intensity can stress people out and make them pull away, which then confirms the feeling of being unheard. The louder you push, the more people retreat. Maybe you begin every exchange with too much force. That can land okay on camera or online, but in everyday life folks call you intense — intense in voice, volume, speed, gestures. You might exaggerate or even brag, not to boast but to prove you deserve attention. This is common among people with trauma histories: it’s not arrogance, it’s a strategy born of the belief that attention must be wrested from others.

You may notice in groups that you often never get a turn — you wait and wait and suddenly the moment has passed. Sometimes that’s because others don’t make space; sometimes it’s because you were taught to hang back and wait for permission that rarely arrives. Being polite is fine, but in many settings permission won’t be handed to you. Many of you tell me you’ve worked on communication skills — you ask questions, show interest — yet others don’t reciprocate. You assume people are selfish, but there’s also something about your demeanor, the signals your nervous system sends, that invites people to keep talking and overlooks you. This isn’t blame; it’s a mix of how they operate and how you learned to show up. There’s an almost magical shift when you start taking yourself seriously, setting boundaries and feeling worthy of being heard: people stop interfering. It tends to change things in unpredictable ways because the change begins inside you.

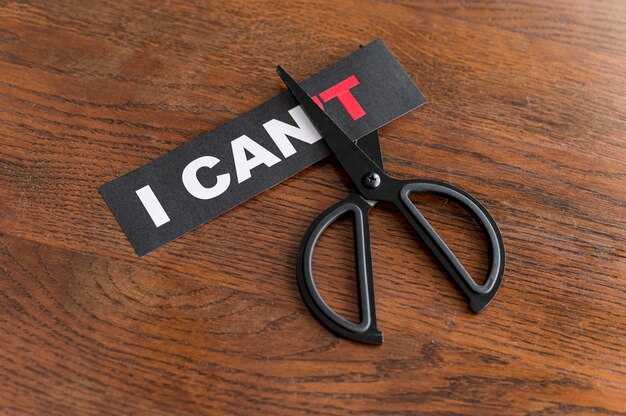

So you need to find your rhythm: speak without apology and claim your space instead of waiting for an invitation that never comes. This pattern isn’t limited to casual talks — it shows up in meetings, creative projects, social events. You could have brilliant ideas but freeze when it’s your moment, or say something and immediately minimize it — “Oh, I was joking anyway” — as if to erase your presence. By undercutting yourself you teach others not to take you seriously. You might feel strongly about injustice or boundaries but deliver your words sideways so they lack impact; or you might explode disproportionately. That kind of emotional dysregulation is a typical adult response to childhood trauma, and it pushes people away. Or you withdraw into silence and ruminate later.

There’s a dynamic at home too: my husband is more introverted and I’m more extroverted. He’ll pause for several seconds and I’ll assume he’s finished, so I jump in only to be told, “Hold on, I’m speaking.” I’ve had to learn to wait and to read the signs so he feels heard rather than interrupted. It hurts to feel disregarded, whether that was intended or not. We all make mistakes, replay conversations and imagine the perfect comeback after the moment has gone. That pattern creates a feedback loop: the more desperate you feel to be heard, the more your attempts produce miscommunications, so you fall into the very behaviors that make being heard less likely. You ramble, over-explain, rush, downplay, repeat, doubt yourself, press too hard, or hold back too much. Nothing feels quite right. The chronic frustration of not being understood can leave you feeling deeply lonely — I’ve spent a lot of life feeling that way. It’s possible to be surrounded by people and still feel invisible, as if you’re performing behind a glass wall waiting for someone to tap and say, “I see you.”

This pattern is a trauma-driven communication style. It’s not about being a bad person; it’s a learned survival response common in those who weren’t truly listened to as children, and it affects relationships, work and social life. You might repeat yourself not because you forget but because you don’t trust that anyone heard you; raise your voice because it feels like the only way to land your words; lower it to sound credible; speak flatly to hide emotion; or adopt a high, unfamiliar pitch. Small changes in how you speak — lowering your register, moving sound out of your nose and into your chest, slowing down — can actually help calm your system and make you feel more yourself.

If you want to practice, try speaking one honest sentence and then stop. Let it sit and see what happens. Usually nothing catastrophic occurs. Each time you express yourself from a regulated place, you give your nervous system a corrective experience. Some people will still interrupt or dismiss you; you’ll learn to recognize that’s their issue, not yours, and you won’t spiral. You can choose to disengage and protect your peace, to pick where you invest your voice, and to look for people who actually want to hear you — those who wait for you to finish, ask follow-up questions, and let you pause. With those people you can be different: you don’t have to perform or entertain. You can speak and be listened to, and gradually that will feel safer and more normal.

If you’re wondering whether past trauma is influencing your life now, here’s a chance to check: download the signs of childhood PTSD quiz by clicking the top link in the description section below. Also, there’s a free daily practice course — short and simple, two techniques to help release harsh, looping thoughts and feelings so you can have more clarity, focus and ease. Follow the free daily practice link in the second line of the description section below if you want to try it.

A personal note: growing up in California and then Arizona, I did two radio internships at 17 and hosted a small Sunday morning show called Tucson on the Air. Hearing myself on the radio, I disliked my voice — it was higher and full of upspeak and a Tucson twang that’s part Texas, part LA. I wanted to sound like a broadcaster, so I deliberately worked on clarity, lowered my register out of my nose into more resonance, and shed the twang. Now when I go back to Tucson it slips out, but otherwise it’s gone. Maybe that feels inauthentic to some, but voice work helped me feel more confident. You might find yourself talking too much when nervous or freezing up completely. You might feel compelled to listen endlessly as if you can’t leave a draining conversation. You can leave. Even if standing up feels rude, it’s ruder to let someone dump on you indefinitely. That freeze response was survival when you were little; your brain learned that compliance felt safer.

When you try to ask for help it might sound angry, vague or accusing and people don’t know what to do, which just reinforces the belief that asking is pointless. But the real issue is you never had safe practice asking clearly. Your brain still thinks it’s unsafe. Even though you can walk away or say, “Do I have your attention? I need to tell you something important,” your nervous system may keep you from asking. So you hint and hope, and when no one notices you feel resentful. Clarifying questions can feel like ambushes, like traps aiming to catch you out — a reaction to not having been understood as a child. Pauses unsettle you, so you race to fill them with words because silence feels like abandonment. If you have an anxious attachment style, a pause can feel like a slammed door and inflame an old wound. Living with these scars is exhausting, but it can improve.

You might leave conversations cringing, replaying every word and thinking you were “too much,” sure the other person is judging you. But most often you were just disregulated, reacting to a ghost of past neglect. And when someone finally truly hears you, it can bring an overwhelming release: tears, a flood of things you’ve kept inside, oversharing not to dramatize but because the dam breaks. Receiving care can feel strange and unsafe, triggering self-sabotage — jokes, topic changes, dismissals — because vulnerability once meant danger. This can go unchecked for years. So you might label yourself shy or awkward, but what’s really happening is that your communication system — your nervous system, beliefs and internal dialogue — was shaped by survival. Survival mode doesn’t aim for connection or dignity; it only aims to keep you safe.

None of this is your fault, but it is your responsibility to change how you communicate if you want different outcomes. The work is about awareness: noticing patterns, tracing their origins, and choosing new responses. You can slow down, breathe, become aware when you’re speaking too quickly, too much, or not at all, and learn to modulate. Ask yourself: am I speaking from the present or from a reflex shaped by past hurts? Stop hedging and apologizing before you even speak. Use concise, clear sentences — they’re more likely to land. Allow silence to exist; treat it as neutral space, not a threat. Notice bodily signs: do you clench your jaw, hold your breath, or speak through your nose? These are clues you’re not grounded and you’re bracing for rejection. Changing physical habits — lowering the pitch, slowing your pace — can help relax you and create a different felt experience.

Begin small. Speak one honest sentence and stop. Each time you do this from a regulated place you’re giving yourself a corrective experience. Some people will still ignore you, but you’ll recognize that’s on them and won’t spiral to prove yourself. You’ll be able to protect your peace, to decide where your voice belongs, and to find people who genuinely listen. With safe people you can be yourself without performance or polish — honest presence matters far more than appearing flawless. Steadiness beats impressiveness; your voice matters. Even if no one taught you how to speak, you can relearn and reclaim that part of yourself: the capacity to express your true self. What could be more important than that? You aren’t too much and you aren’t broken. You’re someone who was unheard learning, now, how to be heard — one truthful moment at a time, one sentence, one pause, one breath. That is how change begins. [Music]

Quand PERSONNE N’Vous Écoutait Enfant… VOICI Ce Que Cela Vous Fait Maintenant">

Quand PERSONNE N’Vous Écoutait Enfant… VOICI Ce Que Cela Vous Fait Maintenant">

Relationship EXPERT reveals Secrets to Connection: Dr. Sue Johnson">

Relationship EXPERT reveals Secrets to Connection: Dr. Sue Johnson">

Êtes-vous entouré de brutes ? La raison cachée pour laquelle vous les laissez entrer.">

Êtes-vous entouré de brutes ? La raison cachée pour laquelle vous les laissez entrer.">

Le comportement de votre partenaire est lié à un traumatisme, mais ce n'est toujours pas acceptable.">

Le comportement de votre partenaire est lié à un traumatisme, mais ce n'est toujours pas acceptable.">

The STRONGEST Sign An Avoidant Still Loves You Deeply">

The STRONGEST Sign An Avoidant Still Loves You Deeply">

If You Shut Down During Conflict, Watch This">

If You Shut Down During Conflict, Watch This">

If Your Partner Says These Phrases, They’re an Avoidant">

If Your Partner Says These Phrases, They’re an Avoidant">

Until This One Shift Finally Made the Avoidant Come Back | Mel Robbins Motivational Speech">

Until This One Shift Finally Made the Avoidant Come Back | Mel Robbins Motivational Speech">

For Healing, Sane Action is More Powerful Than Sad Stories">

For Healing, Sane Action is More Powerful Than Sad Stories">

A Partner Needs to Know About Your Past — But What If You’re Just Dating?">

A Partner Needs to Know About Your Past — But What If You’re Just Dating?">

CHEATING is for SELFISH COWARDS (like me)">

CHEATING is for SELFISH COWARDS (like me)">