When your anger is audible and other people can pick it up in your tone, they often react negatively. And you know what? That reaction has to be acceptable. In a healthy partnership, feeling angry and showing it is fine — indeed, it’s part of a real relationship. The crucial thing is how you show it. Not with cruelty, not incessantly. Those patterns can damage a relationship, especially if there’s simmering resentment or old wounds that haven’t been acknowledged — things people sense even if you don’t name them at the time. Another important question is: even if you express yourself calmly and clearly — because you must speak up for a relationship to exist — is the other person emotionally mature enough to tolerate disagreement or an argument without exploding, abandoning you, or retaliating?

Today’s letter comes from a woman I’ll call Iris. She writes: “Seven years ago I was engaged to a man who had experienced neglect as a child.” I’m going to mark a few points to revisit later, but let’s look at what Iris described. He would become highly reactive whenever my tone revealed frustration. His near-daily comments made me self-conscious. Gradually, any sign of anger was turned back on me — he labeled me as having anger problems, insisted something was wrong with me, and eventually I started to believe it. Our relationship ultimately broke down and I absorbed the blame, especially because I had grown up in an abusive household and never wanted to be aggressive or hurtful. I, too, had childhood abuse that left me with PTSD and led me to your channel. After that relationship ended, I entered another one but was so terrified of being judged that I suppressed ALL my frustration. That relationship became abusive; I tolerated verbal mistreatment because I couldn’t bring myself to stand up. After that breakup I stayed single for four years, vowing not to silence myself again. But in the next relationship the same pattern repeated: the moment my voice rose, I was judged. My partner, whose childhood included traumatic yelling, reacted harshly, which resurrected the shame and self-doubt I had worked so hard to heal. That relationship ended, too, with accusations that I was “yelling.” Now I doubt everything. My natural speaking voice is soft, so when I get passionate the contrast makes people think I’m shouting — but I honestly don’t feel like I’m yelling. I want to be able to show frustration without being condemned for it. I’ve studied nonviolent communication, read books like Anger Busting 101, yet I still struggle with self-blame. I truly believe I’m not yelling, snapping, or aggressive — I’m simply speaking passionately about what matters to me. But if my partner insists that I am, does their perception make it true? Is “normal” someone who never raises their voice? I crave love and acceptance even when I’m upset, without it being used against me. I’m exhausted from trying to be the perfect, quiet girl I was taught to be as a child. How can I signal early in dating that my partner must tolerate my moments of frustration so I’m not judged for them? How do I release the shame at last? All my exes are now in long-term relationships, which makes me wonder: was I the problem all along? Can you help me make sense of this? Thank you.”

Iris, thanks for your letter. It’s a complex situation because I can’t hear your actual voice, and part of why you might doubt yourself is that this pattern has recurred. But it’s hard to conclude you’re the sole problem just because it happened more than once — people bring their own unresolved trauma into relationships and sometimes those dynamics create patterns that are not your fault. One of your relationships escalated into abuse; statistically, if one person becomes abusive, that doesn’t automatically mean you are the cause. If you’ve done the inner work and aren’t abusive, it’s reasonable to hope to find someone who accepts you as you are.

In my own family my mother, who was from Brooklyn, expressed anger loudly. My husband, who grew up in Northern England and is more introverted, sometimes says he can’t read when my tone gets heated — he hears passion as yelling. I completely understand your experience. The key lies in fully saying what you mean while also tempering the intensity so your message lands without unnecessary harm. That often means learning how to make your delivery gentler — adding phrases or softeners that help other people hear you without feeling dismissed or attacked. Growing up in a chaotic home, I (and many people with similar histories) didn’t learn how sensitive others can be; we didn’t realize how much they might feel hurt by perceived criticism. So it’s worth practicing being a skilled communicator who can voice upset and boundaries lovingly. You’ll rarely regret learning to speak with firmness and care.

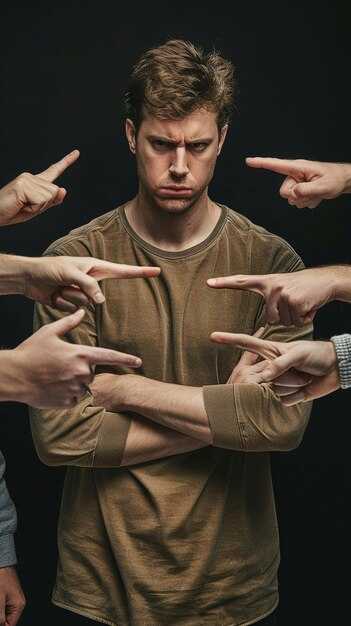

To recap: you were engaged to a man with a neglect background who was easily triggered by any hint of frustration in your voice. When someone is triggered by personal characteristics, it becomes complicated. In communities of people healing from childhood trauma this question appears often. Someone may feel hurt by something another person does, but you can’t reasonably expect everyone to change to remove every trigger. If we required that, nobody could be themselves. There are, of course, behaviors that cross ethical lines or violate boundaries and those deserve confrontation. But when a person is triggered by, say, irritation in another’s voice because it resurrects their childhood pain, that’s their internal wound — and you can’t be responsible for fixing their nervous system.Reactively trying to make others safe by changing your entire self is a trap. The freer and more empowered approach is to reduce how much others’ triggers control your life: decide what you can accept, set boundaries where needed, and choose to avoid people or situations that are too dysregulating. If something is genuinely unacceptable to you, don’t participate in it. If your nervous system is particularly sensitive, some triggers will cause you long-lasting distress, and that’s not a good use of your time. Instead aim for clear communication and practical boundaries.

I applaud your work on nonviolent communication and reading resources like Anger Busting 101. You used the phrase “self-lame,” which I’d describe as remorse — that internal backlash many of us raised in neglectful or abusive homes feel after we speak up. People who experienced childhood trauma often slip into a spiral of self-reproach: “What did I say? Why did I do that? I must be awful.” One purpose of the tools we learn through healing is to accept ourselves, keep improving without tearing ourselves apart, and recognize when we behaved well enough. If you’ve expressed yourself reasonably and compassionately and someone still rejects you because of your tone, it’s clearer that their reaction comes from their own unresolved triggers — something you cannot repair for them.

Trying to “fix” another person’s triggers by constantly adapting your behavior to appease them doesn’t lead to real healing. True healing reduces the trigger response so it doesn’t dominate the nervous system. Out of care, you may choose to avoid certain triggers around a loved one when it’s reasonable and sustainable — for example, not drinking around someone who becomes volatile — but you shouldn’t feel obligated to erase your whole self for the sake of another person’s comfort. People who cling to unresolved triggers are unlikely to be truly satisfied even if you change, because the world will always present stimuli they don’t like. Healing is about regulating one’s reactions and choosing boundaries accordingly.

That said, not every trigger demands neutrality. If someone’s behavior genuinely endangers others or violates basic safety — like driving recklessly near children — you should be fully upset and take action. Trauma tends to blow relatively small slights up to the scale of life-and-death threats, and part of healing is learning discernment: what matters enough to fight for and what can be let go for your own peace.

If someone is chronically upset by your tone and you find yourself constantly altering your expression to avoid triggering them, ask why you remain involved. Early in recovery it’s easy to confuse boundary-setting with controlling someone else. Boundaries are for protecting yourself so you don’t get overwhelmed. You can choose politely not to attend events where you’ll be exposed to triggers you can’t manage right now. But if you’re with someone in ordinary shared spaces — a date at a restaurant, a casual evening — you shouldn’t have to micromanage every small thing they might find irritating unless it’s reasonable. If the mismatch is deep, maybe it’s not the right relationship. Often the fear of abandonment makes us contort ourselves into someone different in order to keep a partner happy, but that rarely leads to a healthy, sustainable connection.

When you’re early in healing, you may erupt because you’ve been suppressing feelings for too long. I’ve watched this happen: people keep quiet to avoid conflict and then eventually explode — that eruption is more destructive than saying something earlier, calmly. So part of learning is practicing timely expression: telling someone “That joke about my looks really hurts” in the moment rather than letting resentment build until you blow up an hour later. Speaking up sooner often preserves the relationship and avoids the remorse that comes from damaging something you care about because you didn’t set a boundary earlier.

I’m glad you’re someone who speaks up. If partners dislike your voice, they might not be the right people to help you gauge how you sound. Ask a neutral observer — a friend or therapist — whether your tone really comes off as angry. I acknowledge the possibility that voice and expression are things we can refine. For many of us, when we’re tired or in a rush, our tone can sound harsher than intended. If you’re with someone who can’t tolerate that occasional friction, you might lack the compatibility needed for a long-term bond.

Practice expressing yourself directly, kindly, and in a timely way. That takes time and repetition; it’s not an overnight fix. Dating is a process to reveal dynamics — if somebody melts down every time you show passion, let that be data that you two aren’t a good fit. Go slow in relationships so you don’t get too attached before seeing whether these incompatibilities persist.

Becoming better at communication doesn’t mean everything is your fault and you should become the silent “nice girl.” That only leads to eventual resentment and outbursts. What helped me distinguish which ways of speaking I should keep and which to adjust was shedding the fear that I’m fundamentally unacceptable in ways I can’t even perceive. Healing requires both honest self-awareness and liberating yourself from trying to conform to everyone else’s expectations. It’s a balance: be willing to own mistakes and grow, but don’t erase your core self to avoid every possible criticism. Different people will require different degrees of gentleness from you; part of healing is learning to attune to that while remaining true to yourself.

A method that helped me unstick the fear and resentment was a daily written practice I teach. Many people find real change by occasionally putting fears and resentments into words on paper and reading them aloud to a trusted friend who understands the method. We don’t generally use it to confront the person we’re angry at — it’s more a private processing tool or something shared with a supportive friend. Be careful, though: listing grievances without using the method properly can intensify distress. It’s a specific technique and it’s simple, but it does require guidance to do safely.

I offer instruction on this practice in a free course and in my book Reeregulated, and I link to these resources in the descriptions beneath my videos. They explain the science, the patterns trauma creates in communication and partner choice, and practical strategies to separate trauma-driven reactions from the parts of you that are authentic. You have a lot of capacity to change the trauma-driven pieces of your behavior; the more you heal, the more your voice and expression will align with your true intentions — friendly when you want warmth, firm and boundary-oriented when that’s needed.

If you want to learn the daily practice, it’s available free and can be learned in less than an hour. There are links that accompany my videos where you can find the course and related materials. Keep working on this — practice, boundaries, and gentleness toward yourself will all help you speak up without carrying the burden of shame. I wish you well and encourage you to keep going.

How to Express Anger Without Ruining Everything">

How to Express Anger Without Ruining Everything">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

THIS PROVES an AVOIDANT Wants You FOREVER (and Loves You Deeply)">

THIS PROVES an AVOIDANT Wants You FOREVER (and Loves You Deeply)">

Why Your Traumatized Self CRAVES ORDER">

Why Your Traumatized Self CRAVES ORDER">

The 5 Unspoken Rules for Making an Avoidant Man Finally Crave a Deep Connection">

The 5 Unspoken Rules for Making an Avoidant Man Finally Crave a Deep Connection">

">

">

J'ai compris pourquoi mes Relations échouaient sans cesse.">

J'ai compris pourquoi mes Relations échouaient sans cesse.">

Est-ce que les limites fonctionnent avec les narcissistes ?">

Est-ce que les limites fonctionnent avec les narcissistes ?">

Conseils pour se rétablir PLUS VITE des effets du traumatisme (Compilation en 4 vidéos)">

Conseils pour se rétablir PLUS VITE des effets du traumatisme (Compilation en 4 vidéos)">

Pornography is EXTREMELY dangerous to your Relationship">

Pornography is EXTREMELY dangerous to your Relationship">

Ce UNIQUE piratage affectif crée des liens indéfectibles avec les personnes évitantes">

Ce UNIQUE piratage affectif crée des liens indéfectibles avec les personnes évitantes">