Being raised amid abuse and neglect nearly always saps a person of their natural strength. You begin to doubt your worth, lose faith in your ability to make things better, and feel powerless to change your life. Recovering that sense of goodness and agency takes enormous effort, persistence, and sometimes a little luck. Yet it’s possible to remember who you are, reconnect to your instincts about what’s right, and believe that you are worth the work of becoming more—kinder, emotionally healthier, more trusting, socially connected, better organized, more patient, more capable, more creative, and financially stable so you have options and some upward mobility. Everyone wants these things, but trauma can seriously undermine your capacity to pursue them.

Dysfunctional families often don’t set out to extinguish the good in a child, but patterns arise that do just that. I’ll point out five ways that growing up with trauma can leave you disempowered, and then move on to how to heal.

First, parents’ conduct—or even their casual put-downs—can implant a narrow or negative picture of who you might become. Your talents go ignored and underdeveloped; without encouragement or guidance they atrophy. You end up having to teach yourself persistence, self-discipline, and follow-through, which is incredibly difficult without role models.

Second, household chaos can isolate you. If home life teaches you to hide, to give up, to shut down or to tolerate abuse, you learn not to assert yourself. That isolation cuts you off from people who are more functional and hopeful—those who could model realistic goals, healthy relationships, and offer opportunities for education or career growth. It’s not simply about class or money; it’s about being around steady, confident people who keep themselves together. That kind of exposure is healing medicine for a demoralized child. Think back: did you have people like that around you? When you met them, could you relax and be yourself, or did they trigger you?

Third, the people who remain in your orbit after isolation are often the ones who reflect the trauma—cynical, stuck, and quick to criticize anyone who begins to rise. When you begin to succeed a little, those who are still hurting can feel threatened and may try to drag you back down with shame, blame, or pressure to conform. There’s a kind of peer pressure that discourages showing strength or reaching up—an almost hostile force that pulls you back into the group. Sometimes that drag is external; sometimes it’s an internal surrender: it feels easier to stop trying, to join the chorus of resentment. But doing so only perpetuates the instability and isolation you were trying to escape, and makes the thought of healing seem pointless. Still, that small healthy voice inside—the part that wants better—remains.

Fourth, loneliness and self-doubt leave you vulnerable to choosing partners who echo your early wounds—people who tear you down yet feel familiar. Out of a hunger for connection you may rush into relationships with someone you know is not good for you, rationalizing the choice. That pattern destroys self-confidence and tightens your social circle around similarly damaged people, risking the repetition of unhealthy family dynamics and passing trauma down to the next generation.

Fifth, a hard upbringing can push your life choices into survival mode: quick, temporary jobs, transient housing, short-term relationships. Burnout, mental scatter, depression, and fear make it hard to hold steady, and yet many of us still feel a persistent inner knowing that life is meant to be more. Even when you’re angry, embarrassed, making mistakes, or sabotaging relationships, a small sense remains that you’re meant for something better. You may have only a flicker of that awareness, but it’s there—an internal ideal self that points toward safety, achievement, and love.

That ideal self is part of your mind even if you’ve never learned how to become that person. Years can pass feeling stuck, as I know from my own story: single parenthood, poverty, undiagnosed CPTSD symptoms, and a sense that life should be different. Yet that yearning persisted, a tiny light just out of reach. Even when I behaved badly—yelled, ruined friendships, fell into bad relationships—I still felt there was more for me. That feeling, even if faint, is precious. It signals that your core values—like kindness—still exist inside you. When you snap at someone and feel ashamed, that discomfort is actually the good part of you noticing that you missed the mark. That moral sense is an indicator of what you’re capable of and want to be.

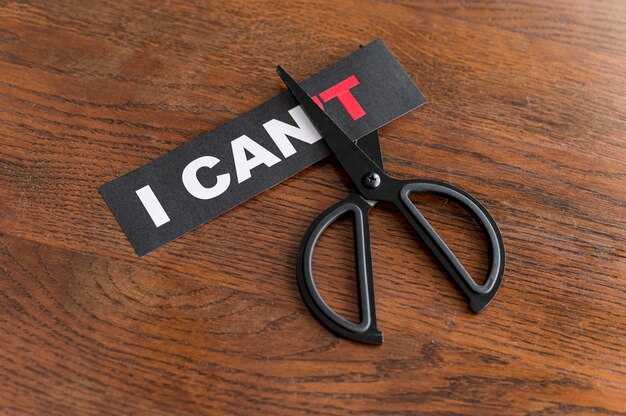

Trauma doesn’t annihilate who you are, but it can block access to your power: imagination, discernment, the ability to change your mind, to create a better life. Healing restores that inner authority by freeing you from trauma-driven thinking—the repetitive fears and resentments that replay the past all day. Thoughts like “I’m no good,” “Nobody likes me,” “I can’t focus,” “I work too hard” or “It’s too late” keep you stuck. Naming those thoughts and asking for them to be removed, or otherwise releasing them, opens space for a different view. If you want a concrete method for doing this, there’s a free set of practices I teach—often called the Daily Practice—that many people have found helpful. It’s linked on my website and in descriptions and includes ways to put these fearful and resentful thoughts on paper and move them out of your head.

Trauma-driven thinking glues you to a disempowered self. If you keep replaying what happened, you remain stuck. What happened to you was real and painful, but it doesn’t have to define you. As you identify and let go of those fear-based thoughts, a clearer sense of who you really are emerges—someone who deserves better and can start to take steps in that direction. When the fog clears, choices appear: you don’t have to stay in a destructive job, live isolated forever, or tolerate abusive treatment. You may not know the exact path yet, but when your true self is alive again, the first step gets easier and the second step becomes visible. Healing is a sequence of small, imperfect moves toward that inner light.

Try things experimentally: test “What happens if I say no?” or “What if I speak up?” and accept that sometimes you’ll screw up and then course-correct. With support and tools, you gain the freedom to make mistakes, learn from them, and close the developmental gaps left by a dysfunctional upbringing. I call that gap a developmental delay because survival in childhood often prevented opportunities to practice adult tasks—planning, steady work, regulated social interaction. Taking small, steady risks with good tools and support helps you grow.

What strengthens you are practical tools and communities. For many, peer groups, 12-step fellowships, and programs like the one I run provide vital support—free or low-cost places to practice new habits, be comforted, and get accountability. My free Daily Practice offers techniques, plus live Zoom calls where people practice together and ask questions. Being around people on a healing path—ideally walking a similar journey—matters enormously. It’s hard to change alone.

When I speak of empowerment, I mean an internal resource—the life force that gives you energy for basic daily actions: getting up, showering, working, leaving a toxic job, learning new skills, holding your ground around difficult people. Empowerment isn’t power over others; it’s the inner capacity to know your next right action and act on it. That power grows through consistent positive actions and by avoiding behaviors that drain you. Complex PTSD commonly erodes this power in many predictable ways. Below I list typical trauma-driven behaviors that sap energy and then outline how to reclaim your power from each pattern.

1) Expecting someone to rescue you. Many people carry a lingering childhood hope that someone will step in and fix things. If caregivers failed you then, you might be stuck waiting for help now. The hardest—but most freeing—realization is that for many parts of your life, you’ll have to step up and help yourself.

2) Believing an apology from the person who hurt you is required for healing. Waiting for that apology hands your recovery to someone else. While an apology can be meaningful, you don’t need someone else’s admission of guilt to start reclaiming your life.

3) Seeking approval from people who demean you. Chasing validation from those who won’t offer it drains you. Learning to approve of yourself—by doing things you can genuinely be proud of—is crucial.

4) Avoiding conflict entirely. There are times when skipping a toxic family dinner is wise, but habitually avoiding all conflict can make you weak at asserting needs, which eats away at your power.

5) Fighting everyone. The other extreme—constantly being combative—also exhausts you and prevents effective problem-solving. Speaking up is healthy; chronic rage is draining.

6) Using intoxicants to regulate. Whether alcohol, cannabis, or other substances, numbing yourself may seem like coping, but it rarely helps long-term re-regulation. Developing sober tools to calm and soothe yourself is far more sustainable.

7) Self-degradation. Excessive negative self-talk and habitual fawning (apologizing for taking up space) undercut your dignity. Aim to act in ways that build self-respect so you don’t have to preemptively put yourself down.

8) Overspending and debt. Financial overextension constrains your choices and ties you to situations you might otherwise escape. Debt reduces freedom.

9) Under-spending and neglect. The flip side—refusing to invest appropriately in yourself—also signals low self-worth. Having decent clothes, underwear, clean bedding, and basic comforts matters.

10–11) Avoiding intellectual growth or learning. If you avoid acquiring the skills and knowledge that would improve your life, you limit your opportunities.

12) Staying friends who drain you. Relationships that constantly diminish you erode self-image and expand the sense of what’s possible.

13) Romanticizing people who can’t commit. Pouring your best energy into someone who will never reciprocate saps your resources and prevents you from recognizing healthy partners.

14) Neglecting self-care. Losing hygiene, health care, or basic personal upkeep diminishes your sense of personal value.

15) Overfunctioning—doing everything for everyone. Taking on too much to be indispensable burns you out and breeds resentment.

16) Underfunctioning—paralysis and procrastination. Avoiding action altogether is equally debilitating.

17) Blaming others for everything. If you live in the past, ruminating about how things would differ “if only” something had not happened decades ago, you lose focus on present remedies.

18) Cutting people out instead of repairing relationships when repair is possible. Habits of fleeing prevent the growth that comes from learning to resolve differences.

19) Staying constantly busy or consumed with others’ problems to avoid your own healing. Running from yourself keeps you from doing the inner work you need.

Now, how do you get your power back? Here are practical responses to those tendencies.

– If you’ve been waiting to be saved, decide to save yourself first. Take responsibility for spotting problems, learning, and seeking solutions, even if you enlist help along the way. Hiring support or having others assist is useful, but the primary ownership of your life will be yours.

– If you believe an apology is required for healing, release that expectation. People who harmed you may never offer the repair you want; your recovery can begin without it. Let go of holding your life hostage to their amends.

– Stop seeking approval from people who won’t give it. Let that invisible elastic snap off and go—free yourself from needing their validation.

– Rather than always avoiding conflict, learn to prepare for and manage necessary conversations. Protect yourself from physically abusive or dangerous people, but don’t let fear keep you mute. Use “front-porch” imagery: allow people to talk while you stand on the porch and decide whether to invite their words into your home. You can listen without allowing their comments to define you.

– If you’re prone to fighting with everyone, develop boundary clarity and regulation tools. Speak up when it matters; avoid blanket antagonism. Learn techniques to stay emotionally regulated during hard conversations.

– Replace substance-based coping with reliable regulation tools. Practices that calm the nervous system—meditation, writing to discharge thoughts, soothing routines—help you re-regulate without intoxicants. A structured practice that includes writing down fearful and resentful thoughts and then resting can be profoundly stabilizing.

– Let go of preemptive self-abasement. Work on actual behaviors that matter: fix things you regret, practice consistent improvement, and approve of yourself when you genuinely earn it.

– For money problems, start tracking income and spending. Make a budget, prioritize paying down debt (snowball or avalanche), and consider community resources (e.g., Debtors Anonymous or other pressure-relief groups). Small, consistent financial choices add up—pay attention to where leaks occur and plug them. Saving and planning give you options and sovereignty.

– If you’re under-spending and neglecting personal basics, set a small, achievable plan to replace worn-out items with appropriate, decent ones. Take the shame out by taking action in manageable steps.

– Improve earning capacity through learning, research, and targeted skill development. Explore career paths that match your financial needs and be willing to ask for raises or seek new roles when necessary. If you’ve chosen work that won’t pay enough for your life goals, consider alternative paths.

– Prune relationships that consistently drain you, or have honest conversations about reciprocity. When you feel better about yourself, healthier people will gravitate toward you. Surround yourself with those who encourage growth, not those who resent it.

– If romantic patterns repeat, recognize the signal: good partners boost your best self. Aim for relationships that make you feel more alive, capable, and encouraged rather than entangled and diminished.

– Start a concrete self-care plan: list ten actions you can take, post it where you see it, and complete at least one item a day—make appointments, go for walks, make a healthy meal, do a hygiene task. Titrate change; small, steady moves beat dramatic swings.

– If you overfunction, negotiate fairness and boundaries. Talk about expectations with the people you help before you exhaust yourself, and recognize when you’re doing too much in hopes of earning love.

– If you underfunction and procrastinate, break the spell by doing one small, pleasurable task to begin momentum. The “empty pocket” feeling that follows giving up old coping is an opportunity to face what’s there—use writing and centered practices to process it.

– Move beyond blame by asking, “What can I do to solve this problem now?” Detaching the problem from the person who caused it frees you to act. Some problems do require outside help (legal, medical), but many can be addressed step by step.

– Before cutting people off, try repair when reasonable. Learn to process your negative feelings so they don’t trap you in rigid responses. Name them, release them on paper, rest, and then see which issues remain worthy of direct action. When repairing isn’t possible or safe, you can choose release—but exercise that option after other avenues have been attempted.

– If you’re overbusy to avoid healing, scale back and allow yourself quiet time to notice what needs attention. The mind often begins solving problems when you give it space.

– Si vous êtes consumé par les problèmes de quelqu’un d’autre, redirigez les soins vers vous-même. Si un enfant dépend de vous, continuez les soins, mais si la dépendance ou le comportement chaotique d’un partenaire domine votre vie, sollicitez de l’aide extérieure et rétablissez des limites.

Si vous vous demandez comment commencer, de courtes pratiques concrètes aident. J'enseigne une Pratique Quotidienne en deux parties : une méthode pour mettre les pensées craintives et rancunieuses sur papier et une brève méditation pour permettre à l'esprit de se calmer et de se recomposer. C'est pratique, portable (stylo et papier) et étonnamment efficace car cela permet de sortir la rumination de votre tête. Les gens l'utilisent pour réduire la roue de hamster de la pensée liée au traumatisme ; beaucoup l'associent à des groupes, une thérapie ou des programmes en 12 étapes.

Ensuite, quelques mots sur le pouvoir de guérison intérieur qui aide à retrouver sa vie. Différentes personnes réagissent différemment aux différentes thérapies ; les approches traditionnelles aident certaines personnes, mais pas tout le monde. Il existe une force de guérison intérieure — une énergie calme et réparatrice que je nomme parfois « la bonne sensation » — qui refait surface dans les moments de détresse extrême et soutient la guérison. C'est comme une douce brise de paix qui vous dit que votre système peut se réparer lui-même. Vous n'avez pas besoin de savoir en détail comment la guérison se produit — votre corps et votre esprit sont conçus pour se réparer lorsque les conditions le permettent. Pensez à l'herbe sous une bâche : une fois la bâche enlevée et que la pluie et le soleil reviennent, l'herbe peut repousser. De même, lorsque vous retirez le piétinement persistant des schémas liés au trauma et que vous vous offrez le bon soutien, vous pouvez renouveler ce que le trauma a obscurci.

J'ai été témoin de cela dans ma propre vie pendant des périodes de crise médicale : après de multiples chirurgies et des complications mettant en danger ma vie, il y a eu des moments où une force vitale renouvelée m'a empli, et étape par étape j'ai retrouvé de la force—marchant un peu plus loin, dormant mieux, pensant plus clairement. Ces incréments de rétablissement se sont accumulés. Ce « pain quotidien » intérieur de force vitale vous ressource et vous aide à revenir à une action significative.

Finalement, voici un exemple de la manière dont cela s'applique à un cas réel. Une femme que je nommerai Naomi a écrit sur une relation de dix ans avec un partenaire qu'elle a décrit comme narcissique, avec des abus répétés, un contrôle coercitif et une responsabilisation inversée à son encontre. Elle a dérivé vers des hommes qui font du bombardement affectif, est devenue la figure parentale dans sa famille et a fini par rester avec un partenaire abusif plus longtemps qu'elle ne l'aurait dû—partiellement à cause de finances, partiellement à cause d'une commotion cérébrale et d'une grossesse, et partiellement à cause de l'attraction familière de l'attachement lié au traumatisme. Après avoir subi des violences, elle a appelé la police ; le partenaire est allé en prison mais a ensuite séjourné dans son sous-sol pendant l'hiver en raison de pénuries de logements. L'enfant, maintenant âgé de six ans, a commencé à refléter des comportements agressifs et abusifs.

À Naomi—et à quiconque se trouvant dans une situation similaire—la priorité est la sécurité et des limites claires. Si quelqu'un est dangereux ou abusif, vous devez vous protéger et protéger vos enfants. Utilisez des refuges, une aide juridique ou des services sociaux si vous en avez besoin. Le bien-être de votre enfant dépend d’un environnement calme, stable et peu dramatique ; les enfants apprennent davantage de la façon dont vous vivez que de ce que vous dites. Protégez votre enfant des conflits entre adultes, obtenez de l’aide professionnelle pour eux si nécessaire et consultez un avocat concernant la garde et la sécurité.

Parallèlement, adressez-vous à vos propres schémas de comportement. Les tendances liées à la formation sur le trauma—ignorer les signaux d'alarme, tenter de réparer les autres, la dépendance financière, répéter les relations qui reproduisent votre douleur d'enfance—peuvent être comprises et modifiées. Commencez par de petites étapes : stabilisez votre logement et vos finances, pratiquez la fixation de limites, connectez-vous à des groupes de soutien, faites quotidiennement un travail de régulation (tel que la Pratique Quotidienne) et obtenez un soutien thérapeutique. Lorsque vous deviendrez plus stable, vous montrerez l'exemple d'un comportement plus sain pour votre enfant et prendrez de meilleures décisions concernant les relations et la logistique de coparentalité. Des ressources pratiques—abris pour les victimes de violence domestique, groupes de soutien à 12 étapes, cliniques juridiques et communautés solidaires—existent pour aider les personnes dans ces circonstances.

Il y a de l'espoir. La guérison est un processus de reconquête progressive de votre pouvoir — en réduisant les schémas de pensée liés au traumatisme, en apprenant à réguler vos émotions, en faisant de meilleurs choix et en construisant une vie avec plus de dignité, de sécurité et de joie. La force vitale intérieure qui vous soutient est présente, même lorsqu'elle vous semble faible ; la nourrir doucement, avec des outils et un soutien communautaire, permet de la développer. Si vous êtes prêt, commencez par des pratiques concrètes, cherchez du soutien et faites un petit pas courageux vers la personne que vous avez toujours été destinée à devenir.

Comment devenir une personne forte et puissante (Compilation en 4 vidéos)">

Comment devenir une personne forte et puissante (Compilation en 4 vidéos)">

Relationship EXPERT reveals Secrets to Connection: Dr. Sue Johnson">

Relationship EXPERT reveals Secrets to Connection: Dr. Sue Johnson">

Êtes-vous entouré de brutes ? La raison cachée pour laquelle vous les laissez entrer.">

Êtes-vous entouré de brutes ? La raison cachée pour laquelle vous les laissez entrer.">

Le comportement de votre partenaire est lié à un traumatisme, mais ce n'est toujours pas acceptable.">

Le comportement de votre partenaire est lié à un traumatisme, mais ce n'est toujours pas acceptable.">

The STRONGEST Sign An Avoidant Still Loves You Deeply">

The STRONGEST Sign An Avoidant Still Loves You Deeply">

If You Shut Down During Conflict, Watch This">

If You Shut Down During Conflict, Watch This">

If Your Partner Says These Phrases, They’re an Avoidant">

If Your Partner Says These Phrases, They’re an Avoidant">

Until This One Shift Finally Made the Avoidant Come Back | Mel Robbins Motivational Speech">

Until This One Shift Finally Made the Avoidant Come Back | Mel Robbins Motivational Speech">

For Healing, Sane Action is More Powerful Than Sad Stories">

For Healing, Sane Action is More Powerful Than Sad Stories">

A Partner Needs to Know About Your Past — But What If You’re Just Dating?">

A Partner Needs to Know About Your Past — But What If You’re Just Dating?">

CHEATING is for SELFISH COWARDS (like me)">

CHEATING is for SELFISH COWARDS (like me)">