Introduction

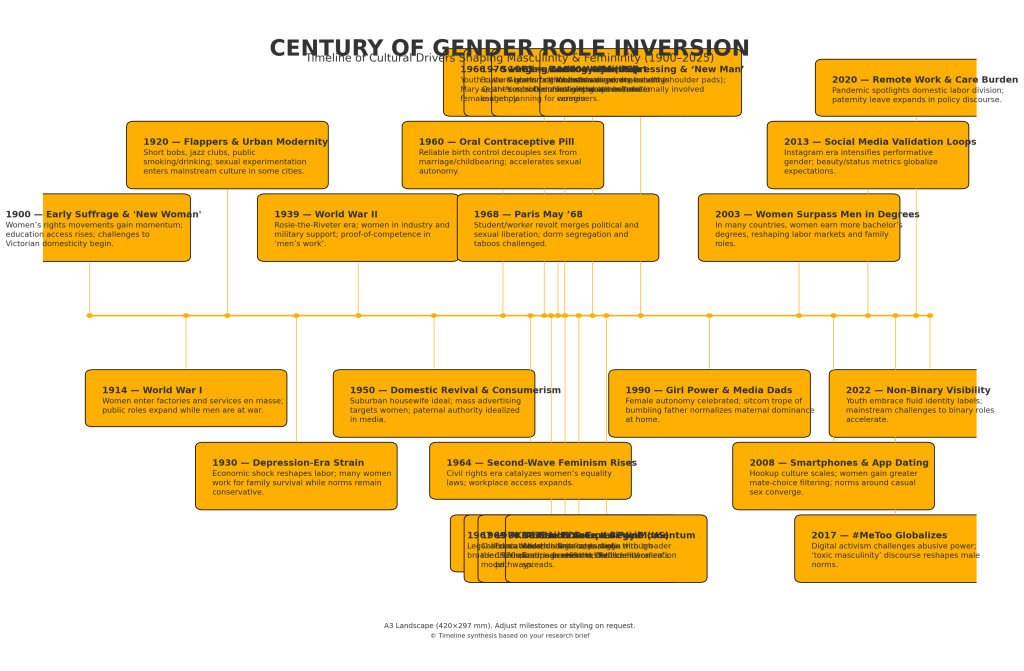

Since 1900, Western societies have experienced profound shifts in gender behavior roles. Traditional expectations—men as decisive breadwinners and heads of families, women as homemakers and caregivers—have been increasingly questioned and upended. Across the United States, United Kingdom, Europe, and Russia, women have gained autonomy and adopted traits once labeled “masculine,” while men have been encouraged (or compelled) to embrace roles and qualities historically deemed “feminine.” These changes did not occur in a vacuum; they were propelled by major cultural forces. Waves of feminist activism expanded women’s rights and opportunities, secularization eroded religious and patriarchal authorities, family structures evolved, and mass media from post-WWII Hollywood films to 21st-century Instagram fed new narratives about what men and women should be. This paper examines how these forces challenged the traditional male-as-family-head paradigm and reshaped male-female dynamics. It will argue that the erosion of rigid gender roles has been double-edged—empowering women and promoting equality, but also contributing to confusion in male identity, unrealistic relationship expectations, and new frictions in dating and marriage culture. Supporting evidence is drawn from historical and sociological research, media analysis, and contemporary commentary on gender relations.

Historical Overview: From Patriarchy to Changing Roles

At the dawn of the 20th century, gender roles in the West were largely governed by patriarchal norms reinforced by law, religion, and custom. In 1900, for example, women in many countries could not vote or hold property on equal terms with men. Middle-class norms idealized a “separate spheres” arrangement: men operated in the public sphere of work and politics, while women were expected to embrace a private sphere centered on home-making and child-rearing. Across the U.S. and Europe, the male breadwinner–female homemaker nuclear family was commonly seen as the natural order, though scholars note this model was not as “ancient” as often assumed. Meanwhile, in the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union, traditional peasant patriarchal structures prevailed into the early 20th century, despite the stirrings of women’s rights movements in urban centers.

However, the 20th century brought disruptive events that began to loosen these strict roles. The two World Wars were especially catalytic. With millions of men conscripted, women were thrust into traditionally male roles in factories, offices, and even military auxiliary units. Iconic propaganda like America’s “Rosie the Riveter” urged women to adopt male-coded traits of strength and independence to support the war effort. In the Soviet Union, gender ideology under Bolshevism initially encouraged women’s emancipation and workforce participation (e.g. early Soviet policies legalized divorce and abortion, and women like Valentina Tereshkova were celebrated as labor heroes and even cosmonauts). Yet, even as women proved capable in these roles, post-war societies often reverted to traditional patterns. In the U.S. during the late 1940s and 1950s, there was a strong cultural push to reestablish the male veteran as family provider and the female homemaker as the feminine ideal, exemplified by suburban domestic imagery in media and advertisements. Similarly, Stalin’s USSR in the post-WWII era extolled motherhood and awarded “Mother Heroine” medals to women with many children, reasserting that a woman’s primary duty was to family (even while she often also held a paying job).

Despite this reversion, the seeds of change had been planted. In subsequent decades, socio-economic transformations and intellectual movements accelerated the breakdown of 19th-century gender hierarchies. The spread of industrialization and higher education opened new employment sectors to women. The demographic impact of wars (with so many men lost) meant women in Europe and Russia simply had to assume greater economic responsibilities. By mid-century, a profound shift was underway: women were poised to claim greater autonomy, and men would gradually adjust—willingly or not—to a new equilibrium.

Feminism’s Waves and Female Autonomy

One of the driving forces in changing gender dynamics has been the feminist movement, which unfolded in multiple “waves” from the early 20th century onward. Each wave challenged traditional gender roles in distinct ways:

- First-Wave Feminism (circa 1880s–1920s): Centered on legal inequalities, this movement won women’s suffrage (e.g. the 19th Amendment in the US, 1918 suffrage in the UK) and greater access to education and employment. First-wave feminists generally did not seek to upend the family structure; many assumed women would remain moral guardians of the home even as they gained public rights. Still, by enfranchising women and asserting their rational independence, this wave planted early seeds of egalitarian gender thinking. In Russia, after the 1917 Revolution, the communist government also promoted nominal gender equality—allowing women to vote and work—though societal attitudes remained conservative in many respects.

- Second-Wave Feminism (1960s–1980s): This wave fundamentally challenged traditional gender behavior norms in Western societies. It critiqued the post-war ideal of the happy housewife, advocating for women’s liberation in all spheres (work, sexuality, family). Second-wave activism led to legal reforms (from the U.S. Civil Rights Act’s sex discrimination ban, to equal pay laws in the US, UK and Europe) and spread birth control access, which gave women unprecedented control over reproduction and career planning. Women en masse entered universities and professions that were once male-dominated. The ideal of the submissive, dependent wife gave way to the “liberated woman”—assertive, career-oriented, and sexually autonomous. In families, this meant many wives now had their own income and voice in decision-making, eroding the automatic authority once granted to husbands. The traditional male breadwinner role was further undermined by rising divorce rates in the 1970s (as no-fault divorce laws passed in many countries) and the normalization of dual-earner households. Men had to adjust to women co-workers and bosses, and to partners who expected more egalitarian relationships. In more secular families, these feminist gains were embraced, while in strongly religious or patriarchal families there was often resistance or a slower pace of change. Still, by the 1980s, even mainstream culture acknowledged that women could “wear the pants” in various situations – literally and figuratively.

- Third- and Fourth-Wave Feminism (1990s–2020s): Later feminist waves continued to advance female autonomy and question gender norms, with an emphasis on individuality and intersectionality. Women’s representation rose in politics and business leadership in the US, UK, and Europe (e.g. Margaret Thatcher’s tenure as UK Prime Minister from 1979–1990 shattered one “masculine” leadership mold). Cultural messaging increasingly celebrated “girl power” (from the Spice Girls in 1990s Britain to a plethora of female action heroes in Hollywood by the 2010s). By the 2010s, a fourth-wave focused on issues like #MeToo (exposing sexual harassment) and rejecting “toxic masculinity.” These currents encouraged men to shed domineering or stoic personas and become more emotionally expressive, egalitarian partners. The cumulative effect of a century of feminism is stark: in much of the West, overt patriarchy is no longer socially acceptable in public, and younger generations take for granted that women can do anything men can. Many women have internalized traditionally “masculine” traits—assertiveness, competitiveness, career ambition—as positive qualities. Conversely, men (at least in progressive circles) are often expected to engage in behaviors once deemed “feminine,” such as open emotional communication, nurturing children, and sharing domestic chores.

It is important to note the divide between secular and religious milieus in how these changes play out. Highly secular societies (like Sweden or the Czech Republic) and families tend to embrace feminist egalitarian norms widely, with men and women viewing themselves as partners of equal authority. In more religious or traditional communities (whether conservative Christian groups in the U.S. Bible Belt, Orthodox communities in Eastern Europe, or Muslim communities), gender role change has been more muted. Patriarchal teachings that “the husband is the head of the wife” still carry weight, and many such families continue to emphasize male leadership and female domesticity. Interestingly, research indicates that both models can yield happy relationships if both partners share the same expectations. A 2019 international family survey found that women reported the highest marital satisfaction either in highly religious marriages with traditional gender roles or in highly secular marriages with egalitarian roles. Partnerships “in the middle” (moderately religious or with mixed expectations) had lower satisfaction. In other words, a devout couple living a traditional patriarchal arrangement can be as mutually content as a feminist-minded couple sharing duties—provided both agree on the framework. What often causes conflict is a mismatch of values during a time of transition: for example, a man raised with patriarchal assumptions married to a woman with egalitarian views (or vice versa). In many societies from the mid-20th century onward, this exact mismatch became common, as generations negotiated between old and new gender paradigms.

Secularization, Family Change, and the Decline of Male Authority

Parallel to feminism, broader cultural shifts—especially secularization and changes in family structure—have eroded the old foundations of male dominance. Secularization refers to the declining influence of religion and traditional authority on everyday life. In 1900, churches (or other religious institutions) in the U.S. and Europe explicitly taught distinct roles: the man as divinely ordained head of the household, and the woman as his “helpmeet.” Over the 20th century, church attendance and religious adherence dropped sharply in much of Europe (and to a lesser extent in North America), particularly after WWII. With this decline in religious authority came a loosening of strictures on gender. States adopted civil laws that overrode religious customs (for instance, allowing married women to own property, or outlawing domestic violence and marital rape, which traditional patriarchal norms often excused). In secular settings, people placed more value on individual freedom than on adherence to sacred gender scripts. Thus, in secular Western Europe by late century, it was not unusual for couples to decide their roles based on practical preference rather than preordained rules—some husbands became the primary cook or caregiver, some wives the main earner, without moral condemnation. By contrast, in societies or subcultures where religious belief or patriarchal custom remained strong (e.g. rural parts of Russia, Poland, the American South, etc.), there was more continuity in male-led family structures. Still, even these areas were not immune to change—urbanization, education, and the influence of global media slowly introduced new ideas.

Changing family structure also played a critical role. The extended family model gave way to the nuclear family in industrialized nations, weakening the wider clan-based patriarchy (e.g. a grandfather’s authority over a whole household). Moreover, from the 1960s onward, Western countries saw a sharp rise in divorce and single-parent households. By 2016, about 23% of U.S. children lived in father-absent homes, a stunning departure from a world where fatherhood was nearly universal. The breakdown of the two-parent family in many communities meant millions of boys grew up with no daily example of a father to model manhood. The reasons for this trend are manifold (economic pressures, liberalized divorce laws, evolving social norms that made unwed parenting more acceptable), but its impact on gender roles is significant. When a generation of young men is raised primarily by mothers, grandmothers, and female teachers, they may absorb more feminine communication styles and conflict-resolution methods by default. They also may not internalize the same expectation of becoming the sole provider or authority figure as earlier generations of boys did. Sociologists have linked father-absence to a host of challenges – higher rates of poverty, crime, and behavioral problems among boys – suggesting that the lack of a stable male role model leaves many young men adrift in terms of defining positive masculinity.

Even within intact families, the breadwinner role of fathers has been diluted. Dual-earner marriages became common from late 20th century onward, and by 2023 in the U.S. only 23% of marriages had a husband who was the sole provider (down from 49% in 1972). Wives are now the primary or equal earners in a large share of families. A Pew Research Center analysis found the portion of marriages where the wife out-earns the husband roughly tripled in 50 years (from 5% in 1972 to 16% in 2022). With women increasingly contributing income, the rationale for automatic male authority (“he who makes the money makes the rules”) weakens. Men can no longer assume a provider privilege in decision-making. Indeed, many couples today strive for egalitarian decision processes, especially when both spouses work. However, the transition can be bumpy. Some men feel emasculated or uncertain of their role if they are not the primary earner; conversely, some high-earning women feel frustrated if their husbands do not adjust to doing a greater share of housework or childcare. Surveys show even in egalitarian-minded marriages, women often still perform more domestic labor on average, which can breed new tensions (“I work all day and do the chores” is a common refrain). The negotiation of household duties and power is ongoing, but clearly the old model of the always in-charge husband has lost dominance in secular contexts.

Crucially, the idea of masculinity itself entered a state of flux. By late century, commentators began speaking of a “crisis of masculinity” – a sense that men no longer know what is expected of them. As one sociologist described, for centuries men had a clear script (“ruler of the world,” protector, provider), but “nowadays everything has changed. Men are stigmatized as oppressors… accused of abusing women and children” in the wake of women’s emancipation. Psychologists like Roger Horrocks observed many men struggling with insecurity or self-destructive behavior “as they could not live up to the ideals of masculinity that patriarchal society expected of them.” The roles of strong patriarch or stoic breadwinner were increasingly untenable or devalued, yet new roles for men were not clearly defined. In religious patriarchal settings, there was less ambiguity—men were told to remain leaders—but in secular culture the message to men could be confusing: be sensitive and supportive, but don’t be a “loser”; cede power to women, but still somehow prove your manhood. This identity ambiguity has fed male anxiety in recent decades, contributing to phenomena like the rise of men’s self-help or “men’s rights” movements aiming to reclaim a sense of purpose.

Mass Media: Evolving Portrayals of Men and Women

Media representations have both reflected and shaped the shifting gender landscape from the mid-20th century to today. In the post-WWII era, American and European popular media largely reinforced traditional gender roles, even as real society was starting to change. 1950s Hollywood and television idealized the nuclear family with a wise, responsible father and a cheerful, domesticated mother. TV shows like “Father Knows Best” (US) or, in the UK, the early soap operas, depicted men as heads of household whose authority was ultimately benevolent and competent. Women, though sometimes portrayed as clever or opinionated (e.g. Lucy in “I Love Lucy” was strong-willed), usually ended up affirming their primary identity as wife/mother. These media narratives reassured war-weary societies that all was back in order: the man was breadwinner-protector, the woman caretaker-nurturer. In the Soviet Union, film and propaganda in the 1940s–50s often showed heroines of labor and war, yet when it came to family, they propagated the image of the self-sacrificing mother and the stalwart father (the latter sometimes as a Party or military figure commanding respect).

By the 1960s and 1970s, media started to crack open the mold. The second-wave feminist influence brought more diverse female characters: e.g. the late-60s American TV series “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” featured a single career-woman protagonist, a novelty at the time. In Britain, “The Avengers” in the 1960s had Emma Peel, a stylish female spy who could fight criminals alongside her male partner—a strikingly empowered role model. Soviet cinema in the 1960s–70s also explored new dynamics; the acclaimed 1979 film “Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears” portrayed women pursuing education and careers (one lead character becomes a factory director) yet still longing for love – reflecting the tension between independence and traditional romance. The very fact that such narratives were popular indicated audiences’ growing familiarity with women stepping into men’s territory at work or in adventure. Male characters, however, were slower to change – in the 60s/70s media they largely remained either heroic (the James Bond archetype, or the cowboy, soldier, etc.) or breadwinners. What did shift was that overt male chauvinism began to be critiqued or played for laughs. For example, Archie Bunker of “All in the Family” (1970s US sitcom) was a caricature of a sexist, domineering husband – and the joke was on him as an out-of-touch dinosaur. Likewise, in Russian comedies of the 70s, bumbling male bureaucrats or patriarchs were sometimes mocked, suggesting that unquestioned male authority was no longer sacred.

From the 1980s through 1990s, media portrayal of gender roles underwent further inversion and experimentation. On one hand, hyper-masculine heroes thrived in the Reagan/Cold War era – think of the muscle-bound action stars of 80s Hollywood (Schwarzenegger, Stallone) embodying a throwback “tough guy” ideal. Soviet films of the 80s similarly had strong military male heroes in Afghan war dramas, etc. Yet, simultaneously, women in media were becoming action heroes and protagonists in their own right (e.g. Princess Leia from Star Wars, Ellen Ripley from Aliens, and later 90s icons like Xena Warrior Princess and Buffy the Vampire Slayer). By the 1990s, Hollywood was producing more female-led stories and also portraying more men who were vulnerable or domestic. A notable pattern in 80s/90s family sitcoms was the incompetent or childish father contrasted with the sensible wife. Shows like “The Simpsons” (where Homer is a well-meaning but buffoonish dad) or “Married… with Children” (where Al Bundy is crass and dim compared to his sharper wife) became the norm. This trend has been documented by researchers: a content analysis of popular sitcoms found a consistent trope of fathers depicted as foolish or immature “other children” rather than authority figures. In one study, nearly 40% of on-screen father portrayals were of the buffoon type – cracking silly jokes, making mistakes – and such fathers were responded to negatively by their children on-screen almost half the time. The implication is clear: the father figure was being culturally demoted from respected patriarch to a subject of humor or mild disdain. A generation of viewers grew up laughing at hapless TV dads, which subtly undercut the idea that real-life fathers must be revered simply for being fathers. As a BYU researcher noted, “more and more often the father is portrayed in TV shows and movies as the wife’s ‘other child’ rather than as a participating parent”. While often intended as comedy, these portrayals carry a message: mothers/women are the competent backbone of family, and men are a bit bumbling – a reversal of the 1950s messaging.

British and European media mirrored many of these trends by the 90s. In the UK, for instance, one could compare the stern father figure of early Coronation Street episodes in the 60s with the dopey dad characters in later British sitcoms. The “cool Britannia” era of the 90s embraced “ladettes” – young women behaving in traditionally male ways (drinking pints, being brash) – as celebrated in magazines and shows, while young men were sometimes depicted as directionless “lads.” In Russia, after the fall of the USSR in 1991, there was an influx of Western media and new domestic productions that explored gender themes more boldly. Russian TV in the 2000s had its own sitcoms and dramas where wives were often shrewd and dominant, husbands comic or inept (for example, the Russian adaptation of Everybody Loves Raymond, titled “Voronin’s Family,” portrayed similar dynamics of a put-upon husband). At the same time, Russian state media under Putin began promoting a neo-traditionalist imagery in other spheres – glorifying soldiers, promoting motherhood – creating a somewhat schizophrenic media environment regarding gender.

Entering the 21st-century digital age, media fragmentation and the advent of social media further changed the game. Not only do we see representation in film and TV continuing to evolve (with more female protagonists than ever by the 2020s – 2024 was the first year women achieved parity in lead roles in top-grossing films), but online media and memes have become influential in shaping gender norms. Platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok allow new narratives (and anti-narratives) about gender to flourish. On one hand, there is an abundance of empowering content for women: from Instagram influencers preaching independence and “boss babe” lifestyle, to female-centered shows on Netflix depicting women as decisive leaders or even aggressors in relationships. On the other hand, online youth subcultures often circulate memes that lampoon both sexes in extreme ways. It’s not uncommon to see viral memes joking that “men are useless” or “men are trash,” and conversely others mocking “career women” or “feminists”. The meme culture has introduced terms like “simp” (a derogatory term for a man who is too submissive or attentive to women) and “Karen” (a mocking label for an overbearing, entitled woman). These slang terms, while humorous, reflect perceptions that men who lack masculine assertiveness deserve ridicule, and that assertive or demanding women are likewise objects of satire. In essence, the internet became a battleground of gender stereotypes and counter-stereotypes, often amplifying the notion that modern relationships are a power struggle.

Crucially, media has filled (or perhaps created) a void of role models. With many real-world young people lacking mentors, they turn to celebrities or online personalities. Some find models of positive masculinity in fictional characters (e.g. the balanced, caring yet strong father figures in some dramas), but others latch onto extreme figures. For example, the popularity of certain misogynistic podcasters or of figures like Andrew Tate among young men suggests that in the absence of clear guidance, media “influencers” will happily supply one. Likewise, young women comparing themselves to Instagram celebrities may adopt an aggressive or materialistic approach to relationships (if that’s what their idols project). The net effect is that media both high and low has steadily normalized women in powerful roles and men in softer or comic roles, contributing to a collective understanding (especially among youth) that women can or should lead, and men ought to yield—or be lampooned if they don’t measure up. As one study noted, heavy consumption of TV with bumbling father characters could lead children to genuinely believe “fathers actually are bumbling idiots” and to underestimate the importance of fatherhood. Media thus doesn’t just entertain; it socializes, for better or worse.

The Impact: Male Identity and Role Models in Crisis

With traditional masculinity diluted and often portrayed negatively, many men have struggled with what it means to be a man in modern culture. The absence of viable masculine role models is frequently cited as a contributing factor to a range of social problems. Historically, boys could look to their fathers or community leaders for a template of manhood; by the late 20th century, those templates were fading. As mentioned, nearly a quarter of American boys now grow up in homes without their biological father present. Schools, especially in Western countries, are dominated by female teachers and often emphasize behaviors like obedience, calmness, and verbal communication—traits that come more easily to many girls than to high-energy boys. Critics have argued this creates a subtle pressure on boys to “act more like girls” in order to be seen as good or well-behaved (a controversial claim popularized by Christina Hoff Sommers in The War Against Boys). Whether or not one agrees fully, it is evident that young men often lack guidance on positive masculinity.

Compounding this, the media’s aforementioned portrayal of men as inept or unneeded has real effects on psyche. Studies show that when fathers are lampooned or marginalized in media, it “contributes to [the] larger stereotypes” that fathers are dispensable. A generation of boys raised on Homer Simpson and other bumbling dads might internalize that a man’s role in family is optional or comical. As BYU professor Justin Dyer explained, after the 1980s “the role of a father is being challenged, [and] becoming vague,” with society even asking “do you actually need a father in the home?”. This ambivalence means that a young man who didn’t have a strong father figure might look to society for cues on how to be a man—only to find confusing messages or negative caricatures. It is no surprise under these conditions that some men experience an identity crisis, feeling alienated or unsure how to comport themselves.

Some have responded by embracing a kind of exaggerated macho persona (a backlash in the form of the “alpha male” trope or involvement in online forums that glorify traditional masculinity). Others swing to the opposite extreme, becoming extremely passive or self-doubting, fearful of asserting themselves lest they be labeled toxic. Neither extreme is healthy, and both can hamper the development of fulfilling relationships. The lack of balanced male role models—men who are strong yet compassionate, who respect women but also have self-respect—has left a vacuum often filled by internet figures with polarizing messages. As one cultural analysis noted, the “widely perceived fear and uncertainty” around the “decline of traditional Western manhood” has fed into a politicized narrative of crisis, which some groups (e.g. certain men’s rights activists or alt-right movements) exploit to rally young men with messages that feminism is to blame for their woes. This environment can distort young men’s understanding of gender relations and breed resentment rather than constructive adaptation.

Women’s Expectations and the Influence of Media

Just as men have grappled with identity in this new era, women’s attitudes toward men and relationships have also been transformed—often in ways influenced by media and pop culture. With greater empowerment and freedom, many women have raised their expectations for a partner. The modern woman in the U.S. or Europe might seek a man who is not only a stable provider (an old expectation) but also emotionally open, egalitarian in housework, supportive of her career, yet still taller and more successful than her (some remnants of hypergamy, the instinct to “marry up”). This sometimes contradictory wish-list can be attributed in part to media and social narratives. Romantic comedies, Disney films, and novels in the post-war decades frequently instilled “fairy-tale” ideals of a perfect mate (handsome, strong, yet sensitive and rich – essentially an amalgam of every desirable trait). Today, social media amplifies the problem by showing curated images of seemingly perfect relationships: Instagram feeds of luxury vacations gifted by one’s boyfriend, or TikTok videos of elaborate surprise proposals and daily gestures that set an extremely high bar for “romance.” As one observation noted, “the media constantly reinforces the idea of what love and dating ‘should’ be” – often an unrealistic, idealized picture that real life fails to match. Young people, surrounded by these messages, yearn for storybook scenarios and can become disillusioned when reality is messier.

Social media and dating apps have also skewed perceptions in mate selection. Online dating gives an illusion of endless choice, yet the way people behave on apps often intensifies selective and superficial criteria. Data from dating platforms consistently show that women, on average, are extremely selective in whom they show interest. For instance, one survey on the Bumble app found that 60% of women set their height filter for men at 6 feet or taller, whereas only 15% were willing to even consider a man who is 5′8″ or shorter. (For context, 5′8″ is around average male height in many countries, meaning a huge swath of men are being automatically dismissed.) While preferences for tall men are not new, apps make such filtering easy and thus more rigid. Similarly, aggregate Tinder statistics reveal that women tend to swipe “like” on only the top few percent of male profiles, effectively competing for a small pool of perceived high-status or attractive men while ignoring the majority. One outcome is that “the top 20% of men are getting 80% of the women” on these platforms (as an often-cited informal analysis suggests), leaving many average men feeling invisible. For women, the flip side is an abundance of attention from men online – but this doesn’t necessarily translate to satisfaction, because many women end up fixating on the most desirable men, who may not commit or even behave decently given their own plethora of options. In short, technology and social media have fed into a climate of “unrealistic expectations” on both sides: some women develop a checklist of criteria shaped by the idealized men they see in media (wealth, looks, height, romance level) and compare ordinary men unfavorably to that standard. Meanwhile, some men develop warped expectations too (perhaps seeking only the most conventionally beautiful women or expecting pornographic ideals of behavior) – though the prompt here focuses on women’s expectations, it’s fair to note this is a two-way street.

Culturally, the narrative for women has shifted to “never settle, know your worth.” This empowering message has a positive intent (encouraging women not to stay in abusive or unequal relationships), but in excess it can foster a sense that no man is ever good enough. Popular discourse often tells women that if a man isn’t meeting all of her needs or expectations, she has the right to demand more or leave. Combined with the highlight-reel comparisons of social media, many women may indeed hold out for an ideal that simply doesn’t exist—a man who meets every criterion. A high school editorial on modern romance trends observes that couples frequently feel they are “always letting each other down by comparing their relationship to unrealistic depictions of others online.” This phenomenon leads to perpetual dissatisfaction: normal relationships, which inevitably have imperfections and lulls, seem subpar when measured against Instagram fantasies or Hollywood endings.

One specific consequence is the delay or decline of marriage in much of the West. Women with higher expectations prefer to postpone marriage rather than “marry the wrong guy.” The average age of first marriage has climbed to the late 20s or 30s in the U.S. and Europe (compared to early 20s in 1900). Many men, sensing women’s exacting standards and fearing rejection or costly divorces, are also less inclined to propose. It becomes a feedback loop—women see few “marriageable” men around them (a complaint often heard is that men are immature or not as accomplished as women), and men see women as too demanding.

Furthermore, the widespread narratives of female independence have diminished the social need for marriage: a woman can earn her own living and even have children on her own (via reproductive technology or adoption), so marriage is more a luxury than a necessity. While this is a great freedom, it can translate into an all-or-nothing approach to partnership: either a man dramatically improves a woman’s life (meeting high emotional and economic standards) or else, many women reason, why bother with a man at all? In secular Western societies, it’s increasingly acceptable for a woman to remain single or single-mother-by-choice, whereas in earlier eras social and financial pressures pushed women into marriage. This means men today must clear a higher bar to be seen as adding value to a woman’s life. In essence, the playing field has changed: women hold more cards and thus can afford to be choosy, but media-fueled choosiness sometimes veers into unrealism, leaving both sides frustrated.

Female Dominance and Male Submissiveness: A New Norm?

As women’s power in society has risen, an interesting cultural trope has emerged: female dominance in relationships, and the corresponding submissiveness (or passivity) of men, becoming normalized or even valorized. Whereas once the henpecked husband or “weak” man under his wife’s thumb was a figure of ridicule (think of old jokes about a man being afraid of his wife’s rolling pin), today it’s often depicted as just the way things are – or even as a desirable, humorous norm. The common saying “happy wife, happy life” encapsulates the notion that a man’s role is to acquiesce to his female partner’s wishes to maintain harmony. Countless sitcoms and commercials show husbands dutifully following their wife’s instructions or seeking permission for their personal choices, a dynamic previous generations would have labeled unmanly but many now accept with a shrug or a laugh.

In many modern portrayals, if a couple disagrees, the smart bet for the man is to yield, because the woman is presumed to know better or will make his life miserable if he doesn’t. This is a stark inversion of old norms where wives were told to submit. Some commentators have argued that this inversion is not merely comedic exaggeration, but reflective of real relationship dynamics. Women, consciously or not, may test their male partners’ limits and assume control if the men continually give in. One analyst of male-female dynamics describes it this way: “From an evolutionary perspective, a man who can be easily controlled is a man who can’t protect [a woman]… So she tests you constantly… hoping you’ll pass by maintaining your boundaries. But when you fail these tests by giving in, she doesn’t respect you more for being accommodating; she loses attraction because you’ve proven you’re not the strong leader she needs.” In other words, if a man surrenders his own needs and principles too readily, the woman may take on the leadership role, but simultaneously feel resentment or disappointment that he let it happen. This perspective, often echoed in the “manosphere” (men’s advice forums, etc.), suggests that many modern relationships fall into a trap of role reversal: the more the man tries to please his partner by ceding power, the less respect and love he receives in return. Indeed, as the same source puts it bluntly, “the more you sacrifice your own needs for hers, the more she resents you for being weak enough to do it.” Eventually, the dynamic flips – the woman becomes the de facto authority, and the man is reduced to seeking her approval, a situation neither truly relishes.

Whether one accepts the evolutionary reasoning or not, it’s clear that female dominance is culturally more accepted now than ever. Women leading in relationships is even frequently portrayed as sexy or humorous (think of depictions of the “dominatrix” archetype in pop culture, or simply the trope of a wife who “wears the pants”). Men being submissive is similarly mainstream in a way that would shock our ancestors. A man who consults his wife for every minor decision might once have been scorned as “petticoat-whipped”; now it’s often seen as a mark of being a good, considerate husband. Part of this stems from a rightful rejection of macho posturing—modern ethics say a man shouldn’t just boss his wife around. But the pendulum can swing far, to where any assertion by a man is framed as aggression, and thus he learns to always defer.

Interestingly, some women openly voice that they cannot find men “strong” enough for them. There is a paradox where society encourages women to be powerful and men to be agreeable, yet heterosexual attraction often still hinges on a certain polarity. Many women don’t actually want a man who is a doormat (constant compliance can be seen as lack of confidence), but they end up with men who have been trained to avoid conflict with women at all costs. This leads to mutual frustration: the woman dominates because the man won’t lead; she then loses respect for him, and he grows bitter or confused about what she really wants. In some cases, this dynamic can become toxic. The extreme end is what one of the sources termed the “gladiator arena” marriage, where a domineering wife turns every interaction into a battle for control, and the husband lives in a “psychological prison” of walking on eggshells. While that description is dramatic, it highlights real scenarios where a man’s fear of being assertive (perhaps to avoid being labeled abusive or simply to keep peace) results in him being perpetually browbeaten. Culturally, we can observe a strain of “female empowerment” messaging that, intentionally or not, validates women exerting power over men. For instance, reality TV shows or advice columns might celebrate a woman “calling the shots” in her relationship as a sign of her strength. Meanwhile, a compliant man is portrayed as sweet or enlightened if done respectfully – but if he’s unhappy, he’s told he must not be “man enough” to handle a strong woman.

One could argue this trend is a form of correcting historical imbalances: after millennia of male dominance, a few generations of inverse power dynamic are perhaps unsurprising. Many couples negotiate these matters fine, trading off leadership in different domains. However, the social script today undeniably tilts toward endorsing female leadership in the home and romantic relationships, especially in media aimed at young audiences. Boys are frequently taught to “respect girls,” which is excellent, but rarely vice versa with the same emphasis; girls are less often explicitly taught to respect boys. In some radical fringes of online discourse, misandry (man-hatred) is flaunted as a form of feminist expression (e.g. the viral slogan “men are trash”). While many women do not literally believe that, the casual manner in which one can denigrate men now—often with laughter from both sexes—indicates a permissiveness toward disrespecting masculinity that did not exist when the pendulum of power was on the other side. For example, social media companies have grappled with whether the phrase “Men are trash” constitutes hate speech; it became popular as a hashtag for women venting about bad male behavior. The very normalization of such a phrase (imagine the outcry if a major hashtag said “women are trash”) shows how far the cultural validation of female dominance or at least male denigration has come.

Consequences for Dating, Marriage, and Mutual Respect

These historical and cultural shifts have had far-reaching consequences on how men and women relate to each other in the realms of dating and marriage, and on the level of respect (or lack thereof) between genders. Some key outcomes include:

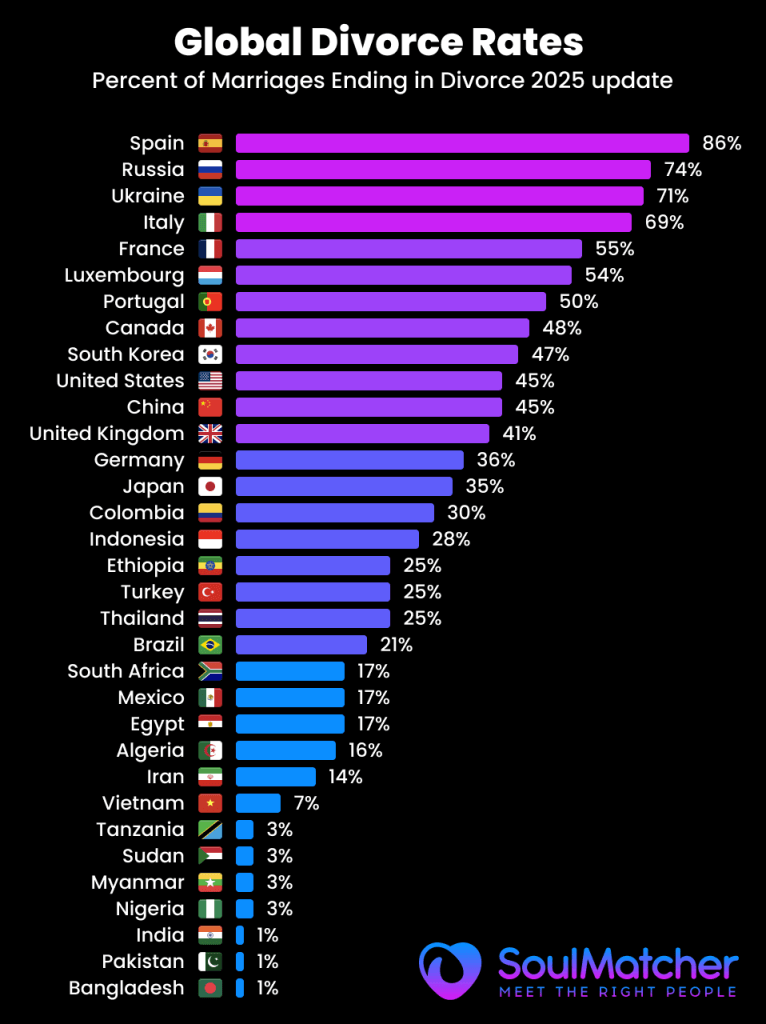

- Marriage Rates and Stability: In many Western countries, marriage rates have declined and those marriages that do occur are more likely to end in divorce than a century ago. A striking statistic related to the role-reversal dynamic is that marriages where the woman is the primary breadwinner are significantly less stable. According to analysis of U.S. Census data, although female-breadwinner households are still a minority (around 16%), they account for an outsized 42% of divorces. In fact, when the wife earns much more, the divorce rate is nearly three times higher than when the husband is the main earner. This suggests that many couples still struggle when expectations clash with reality – the social norm may have shifted to allow women in charge, but perhaps deep-seated attitudes or resentments (on either side) make such arrangements more fragile. Some research posits that men in these situations may feel emasculated or that women may feel the husband is not “meeting expectations,” leading to dissatisfaction. It’s noteworthy that divorce rates are lowest in dual-income egalitarian scenarios, implying that balance or symmetry in roles might foster more stability than extreme imbalances in either direction.

- Male Retreat or Backlash: A visible consequence among men is what some call the “male retreat” from traditional commitments. Feeling uncertain of their role or fearing failure under new rules, some men have pulled back from society’s expectations. This can manifest as young men disengaging from education and career ambition (there are now more women than men graduating university in many places, which is a reversal from 50 years ago), or withdrawing from dating and intimacy (the rise of involuntarily single men, or the “Men Going Their Own Way” movement that encourages men to avoid serious relationships with women altogether). In Japan, a term “grass-eater men” emerged for young men who eschew the assertive masculine image and have little interest in chasing either career or romance. In the West, the term “Peter Pan syndrome” is sometimes used for men who extend adolescence and avoid the challenges of adult manhood, perhaps because the old incentives (being a provider to gain a family) are less clear or rewarding when women can provide for themselves. The net result is a growing cohort of disaffected men. Some channel their frustration into backlash movements – from the mild (nostalgic calls for “real men” and a return to traditional values) to the extreme (online misogynistic communities or even violence, as seen in some high-profile cases of self-identified “incels” lashing out). These are cautionary signs that not all men are adapting smoothly; many feel left behind or belittled by the new norms and respond with either sullen withdrawal or angry revolt.

- Female Frustration and “Finding a Good Man”: On the other side, many women express frustration that they cannot find men who meet their expectations. As women have advanced in education and careers, they naturally seek partners of equal or higher status (a phenomenon predicted by hypergamy). But with fewer men in higher education and some men opting out of high-pressure careers, there is a demographic mismatch. In the U.S., for example, there are now significantly more female college graduates than male; this leads to educated women struggling to find equally educated male partners – a trend sometimes called the “educated women dating dilemma.” Mass media highlights this in stories of “successful women who can’t find a husband,” which in turn sometimes breeds resentment: these women may blame men for not being ambitious or stable enough, while men may blame women for being too picky. The feedback loop continues to erode mutual goodwill. Additionally, some women who do partner with less career-oriented men later report losing respect for them or feeling burdened (the trope of the “man-child” husband who won’t grow up is common in advice columns). In short, while women have more freedom than ever to choose their path, many are finding that the pool of partners who align with their raised expectations has narrowed, leading to either delayed coupling, singlehood by choice, or relationships where the woman begrudgingly “wears the pants.”

- Erosion of Mutual Respect: Perhaps the most worrisome consequence is the subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) erosion of basic respect between men and women. Where once certain courtesies and social codes governed male-female interactions (not all of them good or equal, but they maintained a veneer of respect), now both sexes at times speak of the other in adversarial terms. The prevalence of jokes or dismissive catchphrases (like the “men are trash” meme or men referring to women as “females” in a derogatory tone online) indicates a lack of empathy and understanding. The #MeToo movement highlighted real and pervasive mistreatment of women, but also generated confusion and fear in some men about how to approach women without offending. Some men feel as if they are “walking on eggshells,” worried that a wrong compliment or attempt at flirtation could be branded harassment. This has led a portion of men to simply avoid engagement, further deepening the divide. On the flip side, women encounter circles of men online who speak about women in contemptuous ways (like the extremely pejorative terms used in some incel forums), and this understandably sours their attitudes toward men as a whole. What should be a partnership is, in the worst cases, perceived as a battle of the sexes.

In the domestic sphere, couples must navigate these cultural undercurrents. Many do succeed – it should be acknowledged that a great number of modern men and women have adapted to more fluid roles and report greater happiness in their relationships than was possible in the rigid past. Surveys find that egalitarian-minded couples often have high relationship satisfaction, partly because they communicate more and share responsibilities. Men who are freed from the pressure of being sole provider can develop closer bonds with their children, and women who are freed from total economic dependence can build more equitable partnerships based on mutual choice rather than necessity. These are positive outcomes of the shifts. However, the transition period of the last few decades has undeniably introduced friction and uncertainty. Gender roles are no longer a clear script, but an improvisation, and not everyone is a good improviser. Thus, society at large is witnessing both liberation and discord: liberation in that individuals can now craft roles that suit their personal strengths regardless of gender, and discord in that many feel the opposite sex is not meeting their expectations or respecting them enough.

Conclusion

Over the past century-plus, the cultural landscapes of the U.S., U.K., Europe, and Russia have seen a dramatic renegotiation of what it means to be a man or a woman. Women have stepped into roles once reserved for men – from the factory floor to the highest levels of politics – and in doing so have embraced traits of leadership, assertiveness, and independence that earlier eras labeled “masculine.” Men, correspondingly, have been called upon to adopt behaviors once deemed “feminine” – being more emotionally open, collaborative, and willing to take a backseat at times in family life. These changes were fueled by powerful currents: feminist movements challenging gender hierarchies, secularization weakening the patriarchal authority of religion, economic shifts and wars necessitating women’s workforce participation, and an ever-evolving media environment that both mirrored and molded societal attitudes about gender. Traditional masculine roles, especially the idea of man as undisputed head of the family, have unquestionably eroded in mainstream Western culture, while female autonomy and authority have risen.

These developments have yielded a complex legacy. On one hand, there is much to celebrate – greater equality and freedom, more opportunities for individuals to pursue their talents unencumbered by gendered limits, and relationships that can be founded on genuine partnership and love rather than economic dependency or social contract. Women’s lives have been enriched by the ability to earn, to vote, to lead; men’s lives have been enriched (in many cases) by closer involvement in parenting and the permission to be more human and vulnerable than the old stoic stereotypes allowed. Many families thrive on a model of mutual respect where decision-making is shared.

On the other hand, we must reckon with the unintended consequences. The questioning of “what is a man’s place?” has left some men aimless or angry. The promotion of female strength – vital as it is – sometimes crossed into denigrating male worth, whether in jest or in policy. Mass media’s role in providing role models has been a double-edged sword: even as it inspired women, it often undercut men, and social media’s rose-tinted portrayals have set up all genders with impossible ideals in love and life. The rise of female dominance in some relationship dynamics, and the corresponding male submissiveness, while personally suitable for some couples, appears to cause dissatisfaction in others, especially when it emerges not by conscious choice but by a failure of men to assert themselves and women to respect boundaries. The end result in the dating pool can be cynicism: men complain women only want the top tier of men; women complain men are either too arrogant or too weak. Mutual trust has clearly suffered in this noisy environment of generalized blame.

Moving forward, the challenge for these cultures is to strike a new balance that preserves the gains of equality and autonomy while fostering understanding and respect between genders. Rather than a zero-sum battle of dominance, the goal would be a society where masculinity and femininity are not rigid boxes, but complementary energies that individuals can express in healthy ways. This might involve educating young people (both boys and girls) on positive-sum relationship strategies – emphasizing communication, empathy, and realistic expectations over adversarial “us vs. them” narratives. It also involves creating new archetypes of manhood that are neither domineering patriarchs nor passive bystanders, but responsible, emotionally mature partners. Likewise, encouraging forms of womanhood that value not only independence but also the value of partnership and treating men as allies, not adversaries, will be key. As the data suggests, couples who manage to combine respect with either an egalitarian or agreed-upon role division can achieve high satisfaction. Society at large should take note: the erosion of rigid roles offers an opportunity to build relationships on choice and respect. If men and women can adapt to that ethos—avoiding the extremes of the past and the present—the outcome could be not a crisis, but a new equilibrium where both genders feel valued for their contributions, and each partnership can find the balance of traits that works for them.

In sum, the journey since 1900 has been one from prescribed roles toward negotiated roles. It has been liberating yet disorienting. The “masculine” and “feminine” of 2025 are not what they were in 1900, and they continue to evolve. Understanding the historical forces at play helps explain why women now stand where men once did, and why men are adapting in turn. With that understanding, perhaps we can move past the resentments and unrealistic fantasies toward a culture where equality does not mean sameness, strength does not require the other’s weakness, and mutual respect can be restored as the cornerstone of male-female relations.

Sources

- Britannica – Gender role: Historical shifts in gendered expectations

- Deseret News (2019) – Lois M. Collins, World Family Map report on faith, feminism, and family outcomes

- BYU Daily Universe (2017) – “Fathers combatting negative media portrayals,” citing BYU studies on fatherhood roles

- Social Science Works (2018) – Jeanne Lenders, “The Crisis of Masculinities – A Brief Overview,” quoting Walter Hollstein and Roger Horrocks on male identity crisis

- Spartan Shield (2024) – Muskan Mehta & Katie Haas, “Modern Romance: Media pushes unrealistic expectations in relationships,” on media’s impact on young dating norms

- Evie Magazine (2023) – Gina Florio, “Only 15% of Women Show Interest in 5’8″ Men on Dating Apps,” reporting Bumble survey data on women’s height preferences

- Pew Research Center (2023) – “In a Growing Share of U.S. Marriages, Husbands and Wives Earn About the Same,” statistics on breadwinner role changes 1972–2022

- Gordon & Perlut, Family Law Advocate (2023) – “Women Breadwinners More Likely to Divorce,” citing Divorce.com report on female breadwinner households and divorce rates

Благодарю за интересную подробную статью – разбор смены ролей мужчин и женщин за последние 100 лет, с указанием источников. (правда с некоторыми киноляпами, похоже создана ИИ)

С одной стороны эта глобальная перемена нарушила традиционные вековые сильные опоры мужчин и женщин, отсюда повышенная тревожность, раздражительность и раздражительность. Больше разводов и меньше детей и даже прекращение Родов.

Из плюсов наверное расширение возможностей для самореализации и для тех и других, и больше принятия нетрадиционных творческих мужчин и сильных женщин. И мотивация к равенству и взаимовыгодному партнерству в паре, учитывая природные особенности каждого, как в мире животных)

Как говорится продолжаем наблюдение, куда это всё приведет.

И да нам и нашим потокам предстоит очень интереснейшая задача – найти новый баланс который сохраняет равенство и автономию, способствуя взаимопониманию и уважению между полами, а также продолжению и процветанию Рода человеческого.

Una analisi piu’ equilibrata dei deliri femministi ma purtroppo irrealizzabile perche’ non vuole fare i conti con madte natura e con l’evoluzione biologicacdi millenni.

Il maschile, per natura da sempre e anche nel mondo animale ha la sua ragionecesistenziale nell’essete il Provider e Protector dei figli e della moglie. Questi ruoli non sono un costrutto sociale ma ruoli biologici. L’Ingegneria Sociale promossa, non so da chi, per mano dell”ideologia femminista non puo’ funzionare e gia’ se ne vedono i segni profondi. Gli uomini hanno preso consapevolezza e stanno reagendo e lo faranno sempre con maggiore forza e violenza, perche’ la forza, la sfida, il rischio e il combattimento e’ nel DNA maschile. Perche’ questo esperimento di ingegneria sociale volta a scambiare i ruoli maschili e femminili non puo’ funzionare? Semplice, Perche’ e’ contro Natura, andremo a sbattere su un muro durissimo a velocita’ folle.

Una analisi piu’ equilibrata dei deliri femministi ma purtroppo irrealizzabile perche’ non vuole fare i conti con madte natura e con l’evoluzione biologicacdi millenni.

Il maschile, per natura da sempre e anche nel mondo animale ha la sua ragionecesistenziale nell’essete il Provider e Protector dei figli e della moglie. Questi ruoli non sono un costrutto sociale ma ruoli biologici. L’Ingegneria Sociale promossa, non so da chi, per mano dell”ideologia femminista non puo’ funzionare e gia’ se ne vedono i segni profondi. Gli uomini hanno preso consapevolezza e stanno reagendo e lo faranno sempre con maggiore forza e violenza, perche’ la forza, la sfida, il rischio e il combattimento e’ nel DNA maschile. Perche’ questo esperimento di ingegneria sociale volta a scambiare i ruoli maschili e femminili non puo’ funzionare? Semplice, Perche’ e’ contro Natura, andremo a sbattere su un muro durissimo a velocita’ folle.