Download PDF version:

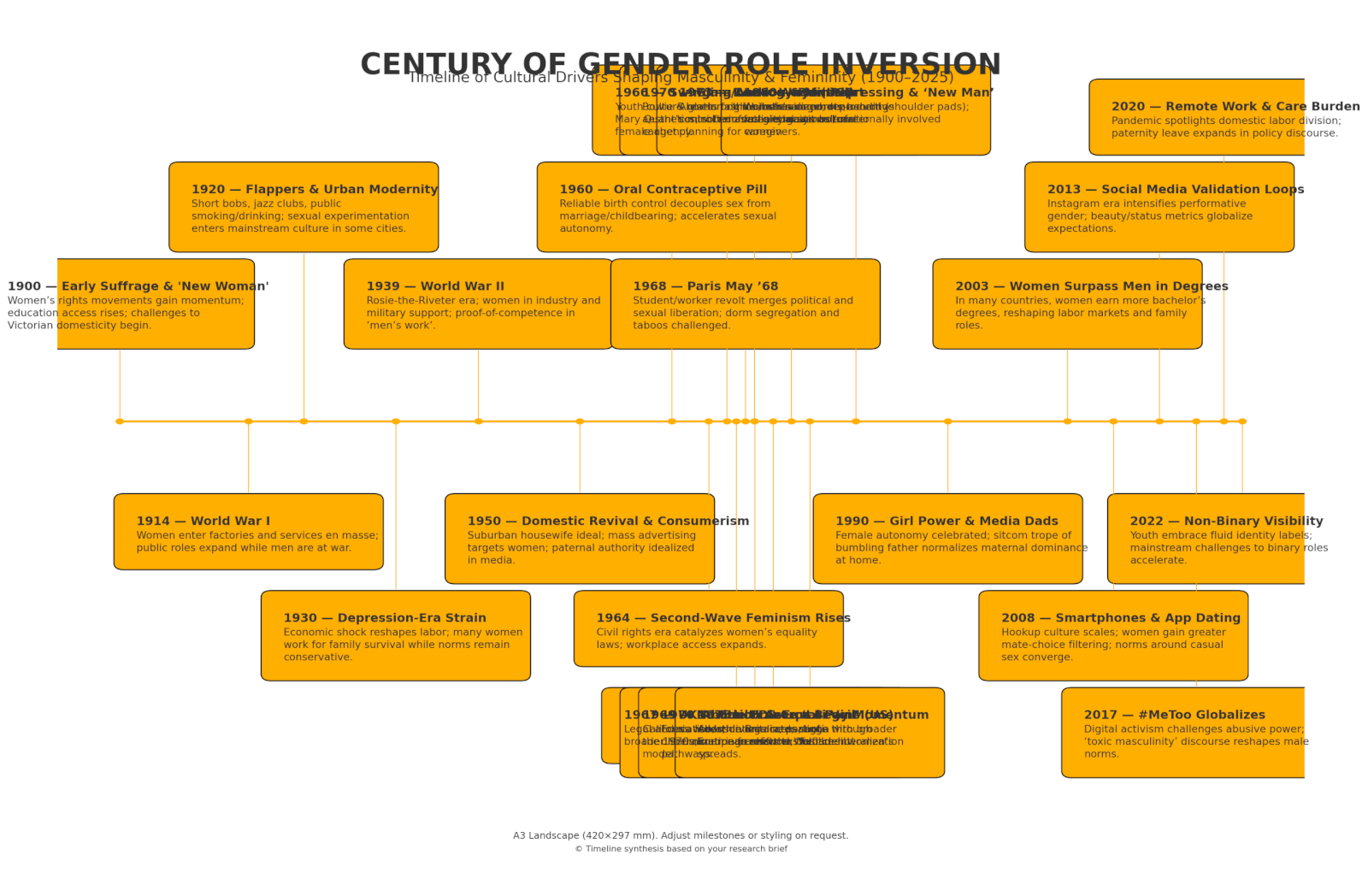

The 1920s: Flappers and Early Women’s Liberation

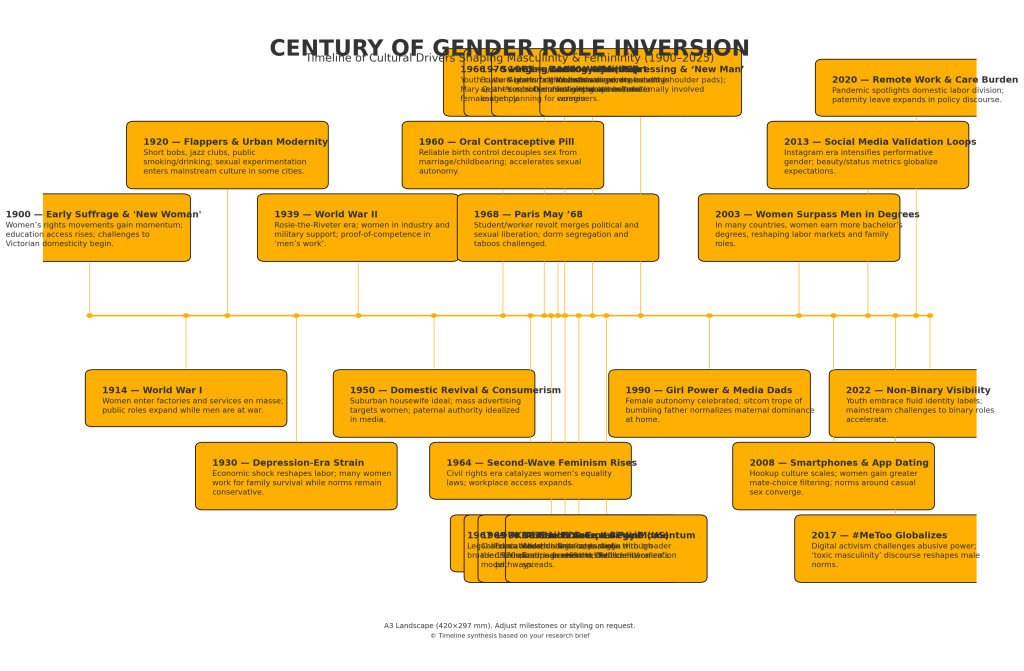

In the wake of World War I, the 1920s saw a dramatic challenge to Victorian gender norms, especially in Western societies. Young “flapper” women cut their hair into short bobs, wore knee-skimming dresses, smoked and drank in public, and embraced a freer attitude toward dating and sexuality. These flappers symbolized a “new breed” of women unafraid of behaviors once reserved for men. The decade began with political emancipation (for example, the 19th Amendment in the U.S. gave women the vote in 1920) and translated that freedom into lifestyle changes. Women joined the workforce in greater numbers and participated in urban consumer culture more independently than before. This era also introduced early experiments in sexual nonconformity; in fact, the 1920s have been described as a period of social and sexual experimentation (influenced by Freudian ideas), during which “bisexuality became chic” in some urban circles. Though full equality remained elusive, the flapper era set in motion social changes that later generations would intensify. In short, the 1920s cracked the mold of “proper” feminine behavior – women openly socialized and expressed desire – planting the seed for a long-term inversion of traditional gender roles.

Post–World War II: Domesticity, Consumer Feminism, and Second-Wave Stirrings

World War II again upended gender roles as women worldwide took on jobs vacated by men gone to war. In the U.S. and Europe, women worked in munitions factories, offices, and military support roles – proving their ability to perform “men’s work.” However, with peace in 1945 came a conservative reassertion of separate gender spheres. Across Western countries, millions of women were “demobilised from ‘men’s work’ to make way for returning servicemen”, returning to domestic life. The 1950s idealized the suburban housewife: media and advertisers glorified women’s roles as wives, mothers, and happy consumers in newly affluent societies. In the U.S., for example, advertising campaigns simultaneously praised women’s wartime industrial contributions and then “encouraged them to take up homemaking” as their patriotic duty once the war ended. Marketers aggressively targeted women with labor-saving home appliances and convenience foods, casting them as the primary consumers of the booming post-war economy. This phenomenon – sometimes dubbed “consumer feminism” – gave women a degree of influence (as household decision-makers) even as it reinforced traditional feminine ideals. Yet underneath the veneer of 1950s conformity, cracks were forming. Women’s education rates were quietly rising, and by the early 1960s many educated housewives felt a “problem that has no name,” a deep dissatisfaction with the limits of domesticity (as articulated by Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique, 1963). The stage was set for the next wave of liberation movements. The paradox of the post-war era was that women were sold an ideal of domestic fulfillment and consumption, even as the experience left many yearning for broader roles – a tension that would fuel the second-wave feminism of the 1960s and 1970s. Notably, in Eastern Europe and Communist Asia, a different model emerged in mid-century: socialist regimes promoted women’s workforce participation as a matter of state policy (e.g. “women hold up half the sky” in Maoist China). While in practice women often bore a double burden (worker and homemaker), state socialism did advance formal gender equality in education and labor. Thus, by mid-20th century, multiple global currents – Western domestic revival versus Eastern egalitarian ethos – were challenging and redefining the age-old division of masculine breadwinner and feminine homemaker.

The 1960s Cultural Revolution: Youth, Sexual Freedom, and Fashion

The 1960s marked an explosion of youth-driven cultural and sexual revolution across much of the world. In the West, this decade – epitomized by “Swinging London” – celebrated modernity, individual freedom, and rejection of old taboos. London became an epicenter of new music, style, and permissiveness: Mary Quant’s miniskirt scandalized older generations but became a symbol of women’s newfound agency over their bodies and fashion. Young women wearing miniskirts (and men with long hair in counterculture fashion) both flouted strict gender dress codes. The introduction of the birth control pill at the start of the decade (approved in the UK in 1961 and U.S. in 1960) was a watershed for sexual freedom. For the first time, large numbers of unmarried women could reliably control fertility, decoupling sex from compulsory marriage and childbearing. This technological and social shift meant women could, in theory, enjoy casual or premarital sex with fewer consequences – a realm previously dominated by men. The “sexual liberation” movement blossomed, encouraging both women and men to view sexual expression as a personal right, not a moral transgression.

In tandem, the decade’s counterculture challenged virtually every pillar of traditional authority, including patriarchal gender norms. Youth in North America, Western Europe, and elsewhere staged protests not only against war and racial injustice but also against the conservative codes that governed relationships between the sexes. “Permissiveness” became a buzzword of the 1960s; conservative critics decried it, but young people embraced more open attitudes toward nudity, cohabitation, and alternative lifestyles. Cultural centers like Swinging London and San Francisco’s Summer of Love (1967) exemplified a coed social world of rock music festivals, “free love” communes, and experimental living arrangements. Women’s liberation groups – the early second-wave feminists – emerged by the late 1960s, directly attacking the notion that domesticity or chastity should constrain women’s lives. The slogan “the personal is political” captured how issues like contraception, sexuality, and family roles were now subjects of public debate. By 1969, American feminists were organizing landmark protests (for example, the 1968 Miss America pageant protest against objectification). In sum, the 1960s shattered many gendered expectations: young women asserted an unprecedented right to sexual agency and public voice, while young men were encouraged (by countercultural values) to be more emotive, pacifist, or communal – traits not traditionally masculine in the militarized post-war culture. This profound cultural rupture laid further groundwork for the inversion of roles, as it normalized behaviors and rights for women that had been masculine privileges, and opened up space for men to step outside the stoic provider role.

Paris in the 1960s–70s: Sexual Experimentation and “Liberté”

If London was about mini skirts and music, Paris was the crucible of philosophical and sexual experimentation during the late 1960s and 1970s. The French student and worker uprisings of May 1968 marked the era’s spirit of liberation. Famously, the Paris rebellion “began with a demand by students for the right to sleep with each other” in university dormitories, exploding into a broader revolt against the “stifling papa-knows-best conservatism” of de Gaulle’s France. In the Latin Quarter, students tore down gender segregation in campus housing as a symbolic blow to traditional moral codes. The slogans of May ’68 mingled Marx with sexual innuendo – “Unbutton your brain as much as your trousers” – signaling how entwined sexual freedom was with the New Left ethos. The upheaval had lasting effects on French society’s gender and sexual norms. Almost immediately, space opened for activism that would have been unthinkable a decade prior: France’s first radical gay rights organization (FHAR – Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire) formed in 1971, and a militant Women’s Liberation Movement (Mouvement de libération des femmes, MLF) also took off. Parisian intellectuals and artists in the 1970s became renowned for avant-garde lifestyles – open marriages, bisexual affairs, and a general rejection of bourgeois family strictures. The celebrated philosophers Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, for example, famously maintained an open relationship with bisexual dalliances, reflecting a broader trend in Parisian bohemia to question the exclusivity of heteronormative pairings. Indeed, the very term “bisexual chic” was applied by the 1970s to the glam rock and artistic subculture (with Paris as one of its hubs) where playing with gender and orientation was fashionable. What had once been furtive or condemned – e.g. bisexuality, cohabitation without marriage – gained a certain cachet among urban sophisticates.

Of course, these liberties were not without backlash. Traditional Catholic and patriarchal segments in France (and elsewhere) recoiled at the erosion of the family values. But the genie was out of the bottle: by the late 1970s, French law itself caught up with cultural change (for instance, legalizing abortion in 1975 and easing divorce), as we discuss next. Around the world, similar patterns played out: Scandinavia embraced sexual openness early (Denmark had a thriving permissive youth culture by late 1960s), Japan experienced a radical student movement and “moga” (modern girls) echoing flapper and hippie sensibilities, and parts of Latin America saw the emergence of countercultural art scenes that pushed gender boundaries (albeit under more repressive regimes). Paris, however, remains emblematic of this era’s “liberté” in matters of love and sex – a key active driver in redefining femininity (as adventurous, not demure) and masculinity (as permissive and non-possessive). The city’s role in social engineering of gender traits was to normalize the idea that personal freedom and authenticity trumped traditional gender expectations, thereby accelerating the inversion of roles.

Legal Reforms: Abortion, Divorce, and the Redefinition of Family

A crucial set of global changes in the 1960s–1980s came via legislation that fundamentally altered marriage, reproduction, and family – domains that historically anchored male and female roles. One major front was the legalization of abortion. The Soviet Union had been a pioneer, legalizing elective abortion in 1920 as an early gesture of women’s emancipation (though it was later restricted under Stalin). But it was during the late 1960s and 1970s that many countries around the world liberalized abortion on a wider scale. For example, Britain’s Abortion Act of 1967 legalized the procedure under broad criteria, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision in 1973 struck down bans and guaranteed American women abortion rights in the first trimester, and France’s “Loi Veil” in 1975 legalized abortion after passionate national debate. Dozens of other nations (from Canada and Germany to India and China) also expanded access to abortion in this era, driven by arguments about women’s health, bodily autonomy, and the social costs of unwanted pregnancies. The impact on gender roles was significant: women’s ability to control fertility meant they could more reliably plan education and careers, undermining the old assumption that a woman’s life would inevitably center on continuous childbearing. It also shifted the power dynamics in sexual relationships – the fear of pregnancy had long been a brake on women’s sexual agency, and with that reduced, women could engage in sex with greater equality to men. In societies as diverse as Italy (which legalized divorce in 1970 and abortion in 1978) and India (which legalized abortion in 1971), these reforms both responded to and further propelled women’s liberation.

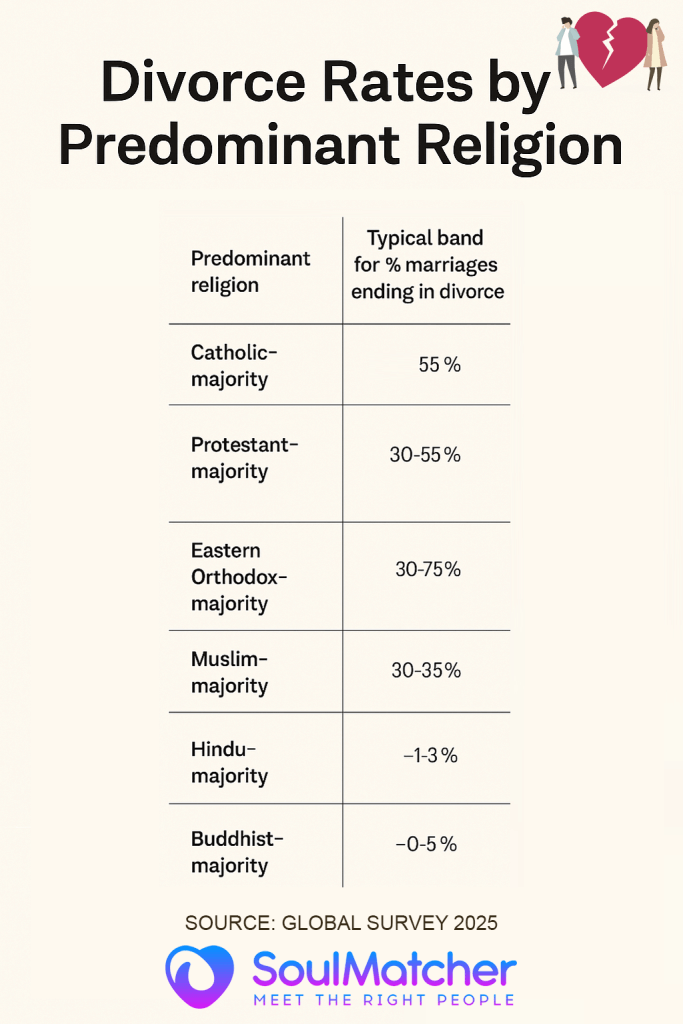

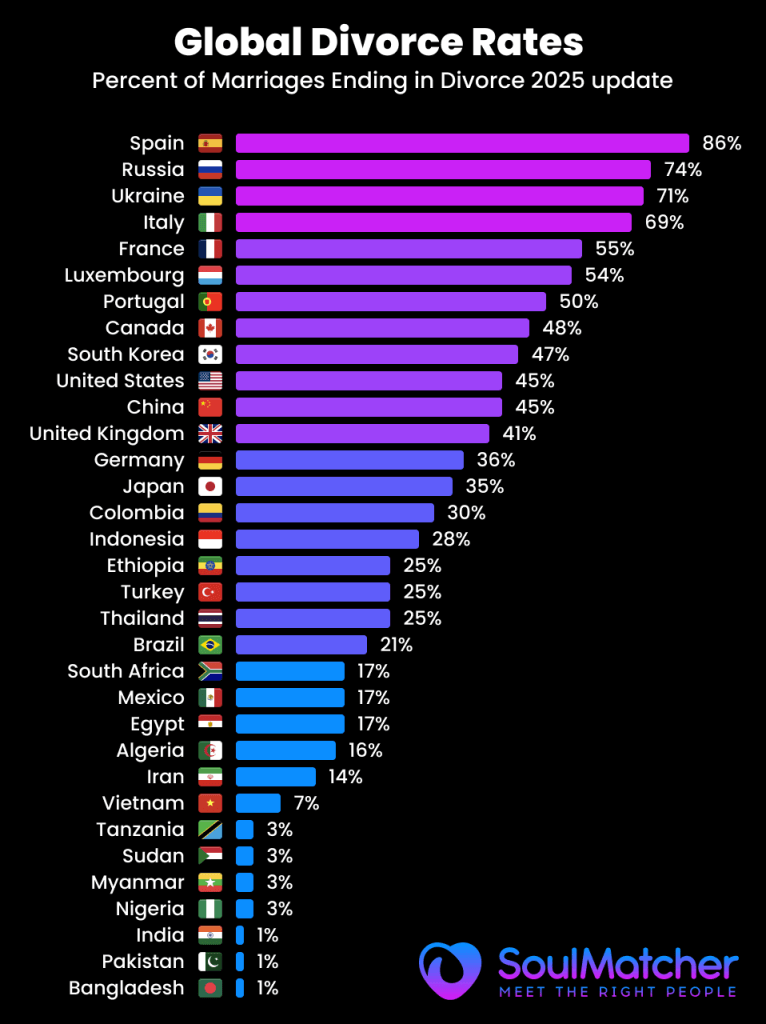

Equally transformative was the liberalization of divorce laws. Traditionally, divorce (if allowed at all) was difficult, stigmatized, and often accessible only by proving a spouse’s wrongdoing (adultery, abuse, etc.), which generally trapped women in untenable marriages due to legal and economic dependency. This changed rapidly around the late 1960s. California’s 1969 no-fault divorce law – the first in the U.S. – allowed divorce by mutual consent without assigning blame. In the next decade, virtually every U.S. state followed suit, gutting the notion of marriage as an indissoluble contract. A similar wave hit other countries: for instance, Britain’s Divorce Reform Act 1969 (effective 1971) introduced no-fault principles, Sweden had earlier eased divorce, and even traditionally Catholic nations eventually yielded (Spain in 1981, Ireland only in 1996, but under strong social pressure by then). The immediate result was a “divorce revolution” – from 1960 to 1980, divorce rates more than doubled in the U.S., and a similar surge occurred in much of Europe. Roughly 50% of American couples marrying in 1970 eventually divorced, compared to under 20% of those who married in 1950. Suddenly, the prospect of a life-long, gendered bargain (male provider and female homemaker bound in permanent union) was no longer guaranteed. Women could exit unhappy marriages and increasingly did so, especially as the stigma lessened. Men, on the other hand, could not count on a wife staying regardless of fulfillment. Researchers note that this era’s spike in divorce was overdetermined – legal changes “opened the floodgates,” aided by the sexual revolution (making extramarital liaisons easier to pursue) and rising female employment and feminist consciousness that gave wives more freedom to leave unsatisfying marriages. The long-term consequences of these reforms for gender roles are complex. On one hand, they freed women from coerced dependence and encouraged greater equality (partners knew each person had to be content or the union might end). On the other, the breakdown of the traditional family structure introduced new social challenges – single parenthood, blended families, and debates about how children fare. Observers at the time spoke of a “crisis of the family,” yet by the end of the 20th century, divorce and remarriage had become commonplace. Men’s and women’s roles within marriage also changed: with the legal option to leave, marriage became more of an individual fulfillment endeavor (“soul mate” model) rather than an institution of duty and sacrifice. This new ethos placed emotional communication and flexibility at a premium – skills traditionally coded feminine – and in many ways pressured men to adapt more than women, since women were no longer expected to tolerate a one-sided arrangement. In summary, the legal liberalization of reproduction and divorce in the late 20th century actively re-engineered the expectations around masculinity and femininity: women gained agency and public rights once denied, while men’s traditional authority in the household was formally curtailed.

Pop Culture and Media: Shifting Images of Masculinity and Femininity

Throughout the 20th and into the 21st century, popular culture, film, and music have been powerful engines of gender role change. They not only reflected evolving norms but often accelerated them by providing new role models and narratives for men and women. In the mid-1900s, for instance, Hollywood began presenting cracks in the facade of the stoic male hero. After WWII, a genre of films emerged highlighting “masculinity in crisis”. Classic leading men like John Wayne complained that on-screen men were becoming “too neurotic”, and indeed characters like James Dean’s Jim Stark in Rebel Without a Cause (1955) or Montgomery Clift’s sensitive roles signaled a new archetype: the vulnerable, emotionally complex young man at odds with the old patriarchal authority. These “sensitive, feminized ‘sigh guys’” (as some critics dubbed them) were often portrayed as sympathetic protagonists struggling with identity, family expectations, or even homoerotic subtext. James Dean’s popularity, for example, indicated a cultural resonance – especially among youth – with a male image that “took on historically feminine characteristics of being both objectified and victimized”, yet remained a hero of his story. This trend in film reflected broader 1950s anxieties about gender: as women gained small freedoms and the Kinsey Reports (1948, 1953) exposed fluid sexual behaviors, traditional manhood felt less secure. Rather than the infallible provider, the male became a subject of scrutiny and introspection in media. In the following decades, film and television would continue to expand the range of acceptable masculinities – from the gentle, family-oriented fathers in 1980s sitcoms to the emotionally vulnerable male leads in 1990s dramas.

For women, pop culture’s evolution has been just as striking. Early Hollywood mostly idealized feminine characters as either virtuous homemakers or love interests, but by the 1960s and 1970s, new images emerged. Television and film started featuring independent, career-focused women – for example, The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970–77) portrayed a single woman thriving in a newsroom career, a storyline almost unthinkable in the 1950s. In cinema, characters like Bonnie in Bonnie & Clyde (1967) or Ripley in Alien (1979) defied feminine stereotypes by being assertive, sometimes violent or in traditionally male roles (Ripley, originally written as a male part, became an iconic female action hero). The portrayal of women as capable protagonists helped normalize the idea that strength, leadership, and intellect were not exclusive to men. Simultaneously, female entertainers pushed boundaries in their personal style and public personas. By the 1980s, pop stars like Madonna took control of their sexual image – mixing feminine glamour with overt power and business savvy – influencing a generation to reject the Madonna/whore double standard and embrace female sexual agency on their own terms.

Perhaps the most flamboyant challenges to gender norms in pop culture came from the music and fashion scenes. In the 1970s, the glam rock movement exemplified by figures like David Bowie (and others such as Marc Bolan and Prince in later years) blurred masculinity and femininity in unprecedented ways. Bowie, in particular, appeared in makeup and androgynous attire, publicly toyed with bisexuality, and adopted theatrical stage personas (like Ziggy Stardust) that defied gendered expectations. On the cover of a 1972 magazine, Bowie was provocatively asked “Are You Man Enough for David Bowie?”, underlining how his very presence challenged what it meant to be a man. Bowie “refused to conform to ‘masculine’ expectations,” using fashion and performance to liberate himself and encourage fans to do the same. As one analysis notes, his unconcern for traditional masculinity – being “in touch with both masculine and feminine aspects” of himself – drew in young people who “ached to be free” of societal constraints. The glam era’s gender-bending style (men in glitter, women in tuxedos, etc.) had a ripple effect: it planted seeds of acceptance for later expressions of non-binary or fluid gender identity. By the late 20th century, it was far less shocking to see a male pop artist in eyeliner or a female one with a shaved head, whereas such things would have caused outrage in earlier decades.

Popular media also directly tackled gender issues: the 1980s-90s brought feminist themes into mainstream film (e.g. Thelma & Louise in 1991, a female buddy/road movie that flipped the script on male outlaws) and literature (the rise of feminist and LGBTQ authors gaining wide readership). Moreover, the global reach of American and European pop culture meant that these new images of manhood and womanhood were disseminated worldwide. A teenager in Brazil or India in the 1990s, for instance, could watch Western films or music videos and be inspired by the sight of women rock stars or compassionate male heroes, subtly influencing local gender norms. Conversely, local film industries also began to reflect change: in Bollywood, starting in the 90s and 2000s, one sees more portrayals of career-women protagonists and sensitive, egalitarian romantic heroes, indicating a shift from the hyper-macho and coy-feminine formulas of earlier Indian cinema. In sum, pop culture has actively engineered gender traits by providing new archetypes: it taught men that it could be cool to be caring (think of the evolution from James Bond’s unyielding machismo to the more emotionally torn heroes of recent action films), and it taught women that assertiveness and autonomy could be admirable (the celebration of “girl power” in the 1990s, for example). The long-term effect is a generation that grew up with more fluid notions of what men and women can do – a cultural undercurrent essential to the inversion of traditional roles.

Education and Workplace: Convergence of Roles and “The New Woman”/“New Man”

Another decisive arena of gender role transformation has been access to education and inclusion in the workforce. Around 1900, in most societies, higher education was predominantly male, and most married women did not work outside the home. That picture has been utterly reversed in many regions by the 21st century. In the United States, for instance, women went from earning only 24% of bachelor’s degrees in 1950 to about 50% by the early 1980s, and today they surpass men – by 2003 there were roughly 1.35 female college graduates for every 1 male, a complete flip from 1960 when men outnumbered women 1.6 to 1. Similar milestones have occurred globally: women now enroll in universities in greater numbers than men in Canada, much of Europe, Latin America, and parts of Asia. This educational revolution has been both a driver and a result of shifting gender norms. As more girls received higher education, they delayed marriage and aimed for careers, not just “jobs until motherhood.” By the late 1960s young women’s expectations had “changed radically” – they began taking traditionally male-dominated subjects (science, law, medicine) and envisioned themselves as future professionals. In turn, their academic success challenged old assumptions of male intellectual superiority and created cohorts of women qualified for leadership roles. The workplace slowly absorbed these changes. Women’s labor force participation climbed sharply from the 1960s onward – in the U.S. it rose from under 40% of adult women in 1960 to 60% by 1999, before plateauing. Across Western Europe, female employment also surged in the 1970s–1990s as economies transitioned to service industries and laws outlawed gender job discrimination. Even in countries with traditionally low female workforce participation (due to cultural norms or religion), such as parts of Southern Europe or the Middle East, the late 20th century showed gradual increases, especially in urban areas and in education and healthcare sectors.

The influx of women into workplaces once dominated by men is a direct inversion of historical roles – women as breadwinners and executives, men adjusting to not always being the primary earners. By the 1990s, it was common in many countries to see women as doctors, lawyers, professors, politicians, and soldiers. Some nations even saw women lead governments (from Indira Gandhi and Margaret Thatcher in the 20th century to many more in the 21st), breaking the ultimate “male” role of political leadership. While gender pay gaps and glass ceilings persist, the cultural impact is profound: a boy growing up in 2025 sees women routinely in authority – as teachers, bosses, perhaps as his country’s president – something that would have been rare or null a century prior. This normalizes traits like assertiveness, analytical thinking, and strategic decision-making as human traits, not exclusively masculine ones.

Conversely, as women took on more paid work, men gradually engaged more in domestic and caregiving roles. The late 20th century gave rise to the concept of the “new father” – a dad who changes diapers, pushes the stroller, and is an equal co-parent rather than the distant breadwinner of old. In Europe and North America, especially, fatherhood ideals shifted from the authoritarian disciplinarian of the 1950s to the sensitive, involved father figure by the 2000s. Parenting advice literature and media began to celebrate men who could nurture; a popular saying was that “today’s good father is as adept at changing diapers as changing tires.” This cultural push was partly necessitated by reality (dual-income households required fathers to share childcare) and partly ideological (feminist and psychological research emphasized a father’s emotional role). Many countries introduced paternity leave or “parental leave” policies in the late 20th and early 21st century, explicitly encouraging men to take time off work for newborn care – a concept that would astonish a 1950s employer. In some Nordic nations, such policies have led to a majority of new fathers taking substantial leave, solidifying the expectation that men can be as hands-on in infancy as mothers. The net effect is that certain skills and traits – patience, tenderness, homemaking – once seen as inherently feminine are now shared human skills. Young men today are generally expected (and often willing) to cook, clean, and tend to children, in contrast to the strict role segregation of their grandfathers’ era.

In the realm of education of children, schools since the 1970s have also tried to undo gender biases: textbooks increasingly avoid portraying only boys as doctors and girls as nurses, for example, aiming to widen aspirations. Programs encouraging girls in STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) and, conversely, attempting to engage boys with emotions and communication (to reduce aggression and dropout rates) represent conscious social engineering to balance gender traits. However, these changes have come with new challenges. Girls’ academic performance soared (to where in many countries girls outperform boys at most levels), and educators now grapple with how to address an emerging “boys’ crisis” in education – some argue that traditional boyhood energy is being pathologized, and male role models in teaching are scarce. On the home front, women now shoulder the “double burden” in many cases – expected to excel at work and still do more parenting – which has prompted calls for men to step up even further at home. Clearly, the equalization of education and work has not fully inverted every aspect of gender roles, but it has significantly eroded the old notion that one’s sex should determine one’s sphere of life. A long-term consequence visible now is that men and women often work side by side and share family duties, negotiating roles based on personal strengths rather than preset social rules. This ongoing negotiation is itself a hallmark of inverted and fluid gender roles.

The Digital Age (2000s–2020s): Hookup Culture, Social Media, and Digital Gender Activism

In the 21st century, several new cultural forces have emerged that continue to drive (and sometimes complicate) the evolution of gender roles globally. One is the mainstreaming of a “hookup culture” among youth and young adults. With the rise of the internet and smartphones, dating norms have shifted towards more casual, immediate encounters – often initiated through apps and social media – rather than traditional courtship. The term “hookup” (implying casual sexual or romantic encounter with no commitment) became widespread in the 2000s. While casual sex certainly existed in earlier eras (indeed, the sexual revolution of the ’60s made it more acceptable), what’s notable now is a broad acceptance of both men and women participating in non-committal intimacy. On college campuses and beyond, it’s generally as socially permissible for a young woman to have a one-night encounter as it is for a young man. This represents a significant inversion of the double standard that prevailed through most of history, where men’s promiscuity was tolerated (even bragged about) but women were harshly judged for the same behavior. Studies of contemporary youth find that motivations for “hooking up” are similar across genders – ranging from physical gratification to seeking an eventual partner – and that women are actively exercising their sexual agency in these contexts, not merely acquiescing to men. Technology has been a catalyst: dating apps like Tinder, Bumble, and their global equivalents give women a say in initiating contact (Bumble, notably, requires women to message first, flipping the pursuit script). However, the rise of hookup culture also brings new dynamics to navigate. Some researchers and social critics express concern about emotional disconnect or the impact on long-term relationship formation, and indeed there has been a partial counter-movement among youth valuing more “authentic connections” over the swiping-driven dating scene. Nevertheless, the overall effect has been to further liberate women’s sexual behavior into parity with men’s, and to push men to adjust to women’s greater selectivity and independence in the mating market.

Social media is another double-edged sword in the gender arena. On one hand, platforms like Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok have provided avenues for individuals to express identity in creative ways, giving visibility to diverse gender expressions. For example, androgynous or non-binary influencers can attract large followings, thereby normalizing variance in gender presentation for a mass audience in a way earlier subcultures could not. On the other hand, social media has arguably intensified pressures around gendered appearance and validation. Adolescent psychology studies indicate that girls and young women often face heightened anxiety and self-objectification in the Instagram age – competing for “likes” can reinforce the notion that their worth is tied to beauty and desirability, echoing older patriarchal standards in a new form. Men, too, curate images for validation: the rise of the “influencer” means young men might feel pressure to display traditionally masculine markers – muscular physiques, luxury possessions – to garner status online. In this sense, social media can perpetuate certain stereotypes (e.g., women as objects of beauty, men as performers of success) even as it breaks others. Another phenomenon is the emergence of “validation culture,” where both women and men seek constant feedback on their lives. Some sociologists argue this has led to a form of digital social engineering: people actively shape their gendered self to fit whatever garners attention in the algorithm, be it hyper-feminine aesthetics or hyper-masculine posturing, while others deliberately subvert those norms to stand out. Importantly, social media has also allowed transnational dissemination of feminist and gender-progressive ideas. A fashion trend or campaign challenging gender norms in one country can go viral and influence youths in another overnight. For instance, a trend of young men painting their nails or wearing skirts in South Korea or Mexico owes partly to seeing Western celebrities do it on social media, combined with local youth culture’s own innovators.

Lastly, the digital age has supercharged gender-related activism and discourse. The #MeToo movement that exploded in 2017–2018 is a prime example: what began as a hashtag for women to share experiences of sexual harassment became a global rallying cry that toppled powerful men in industries from Hollywood to government. In 2018, observers noted that “around the world, women stood up and spoke out about the abuse they have faced at the hands of men,” often using social media as their platform. #MeToo not only raised awareness about issues like workplace harassment and consent, but it also sparked conversations about “toxic masculinity” – questioning cultural norms that encouraged men to assert power in harmful ways. Digital activism has also brought attention to LGBTQ+ rights: campaigns for transgender acceptance (#TransRightsAreHumanRights) and non-binary recognition have gained international momentum via online communities, challenging the very binary of male/female that underpinned traditional gender roles. In parallel, men’s movements have also flourished online – ranging from positive groups advocating involved fatherhood or men’s mental health, to reactionary communities (such as “incels” or certain men’s rights forums) pushing back against what they perceive as the excesses of feminism. The clash of narratives is very visible on the internet: for every feminist campaign, there is often a counter-thread of misogynistic trolling; for every celebration of role inversion, there are voices decrying a “loss of manhood” or “assault on femininity.” This cacophony is itself evidence that gender roles are in flux. The long-term consequence of digital activism is still unfolding, but it has undeniably accelerated the globalization of gender debates. A local custom or law seen as oppressive can be called out by international audiences, and likewise progressive changes can diffuse more rapidly. In terms of social engineering, one might say that the internet has become a battleground where ideas of masculinity and femininity are continuously deconstructed and reconstructed via memes, campaigns, and influencer lifestyles.

Conclusion: Gender Role Inversion and Its Long-Term Consequences

Over the past 125 years, the cumulative impact of these cultural, political, and technological forces has been the breakdown of rigid masculinity and femininity and a relative inversion of many gendered behaviors. Women across the world have, to varying degrees, adopted roles and traits once labeled masculine: they earn advanced degrees, lead corporations and nations, openly express sexual desires, and define their identities beyond wife and mother. Men, for their part, have increasingly been drawn into traditionally feminine spheres: from hands-on parenting and domestic work to greater emotional openness and cooperation with female peers rather than automatic dominance. The two genders (and indeed, those who identify outside the binary) have become more alike in their social roles than at any time in recorded history. This is not to say absolute equality or interchangeability has been reached, but the trend lines are clear. Sociologists note that many societies have shifted from complementary gender roles (each sex fulfilling opposite, “completing” functions) toward egalitarian or fluid roles, where individuals negotiate tasks and traits irrespective of gender. We see women excelling in military combat and men excelling in nursing and early childhood education – realities that invert centuries of assumption about physical prowess and nurturing instincts.

The long-term consequences of this role inversion are complex and still unfolding. On one hand, there are evident social gains: increased gender equality correlates with higher economic development, greater innovation, and more individual freedom. Women’s liberation has improved outcomes in health, education, and human rights for roughly half the population. Men’s liberation from the “stiff upper lip” constraints has arguably led to richer emotional lives and the allowance to be caregivers and not just providers. Families in which partners share roles tend to report higher relationship satisfaction and more adaptive children in many studies. However, these shifts also bring new tensions and challenges. The traditional template for how to form a family and live one’s life has been destabilized – leading to what some call the “post-modern” family era. Marriage rates have fallen in many countries (for example, far fewer millennials marry compared to their grandparents), and those who do marry do so later and more as a choice than a necessity. Birth rates have plummeted in developed societies, in part because women empowered with education and careers choose to have fewer children and later in life. This raises demographic and economic concerns about aging populations and labor forces. The higher incidence of divorce and single parenthood, while reflecting personal freedom, also means many children grow up with one parent, which can exacerbate financial and social stresses (often mothers shoulder single parenthood – an ironic burden of “liberation”). Additionally, some men have struggled to find a new identity in a world where women don’t need them to be providers or protectors in the old sense. The phenomenon of the “fragile” or “lost” man in the post-feminist era is often discussed – evidenced by, for example, young men dropping out of college or work at higher rates, or gravitating to extremist ideologies that promise a return to clear roles. In parallel, women face the “superwoman” squeeze: expected to succeed in career, maintain a perfect home, and conform to societal pressures of beauty and motherhood – a tall order that can cause stress and burnout, indicating that equality in expectations has perhaps outpaced equality in supportive structures.

Culturally, the dialogue continues: what is toxic masculinity versus healthy masculinity? Should society encourage men to be more traditionally masculine or further embrace their feminine sides? Are women truly happier after shedding traditional roles, or do many secretly yearn for the clarity of defined expectations? Different groups and regions answer these questions differently. For instance, Scandinavian countries, which are among the most gender-equal, also report very high life satisfaction and have normalized gender-neutral parenting and work policies. In contrast, some societies that rapidly adopted Western gender norms feel a backlash – segments of populations calling for a “return” to tradition in the face of what they perceive as social unraveling (this is seen in movements in parts of Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and even the U.S. with certain conservative or religious revivals). The reality likely lies in a balance: the gains from freeing individuals from rigid roles are immense, but humans are also adjusting to a new social equilibrium. Gender role inversion, in many ways, is an experiment still in progress – an engineered social evolution with no historical precedent for reference.

From an academic perspective, one can conclude that the drivers of this century-long shift have indeed been active: each cultural trend – be it the flapper’s defiance, the housewife’s consumer empowerment, the feminist protests, the rock star’s androgyny, or the viral hashtag – has deliberately or inadvertently reshaped the “social script” for gender. The roles of “masculine” and “feminine” are no longer opposite and fixed, but points on a spectrum of human behavior that individuals can mix and modify. As one cultural commentator looking back observed, the ultimate legacy of these global trends is a world where an individual can ideally be “free of taboos, experimental, in touch with both masculine and feminine aspects of themselves”, a more integrated humanity beyond the old binaries. While traditionalists may mourn what’s lost and progressives celebrate what’s gained, scholars will continue to analyze this grand social transformation for decades to come. The inversion of gender roles – set into motion by the 20th century’s upheavals – remains one of the most consequential and defining developments of modern social history, actively engineering new traits and possibilities for all people in society.