Introduction and Key Takeaways

Divorce rates – measured here as the percentage of marriages that end in divorce – vary dramatically worldwide. Cultural and religious norms play a significant role in shaping attitudes toward divorce, alongside legal frameworks and socio-economic factors. Predominantly religious societies that discourage or prohibit divorce tend to have far lower divorce incidences. Meanwhile, more secular or permissive cultures often see higher divorce rates. Key takeaways include:

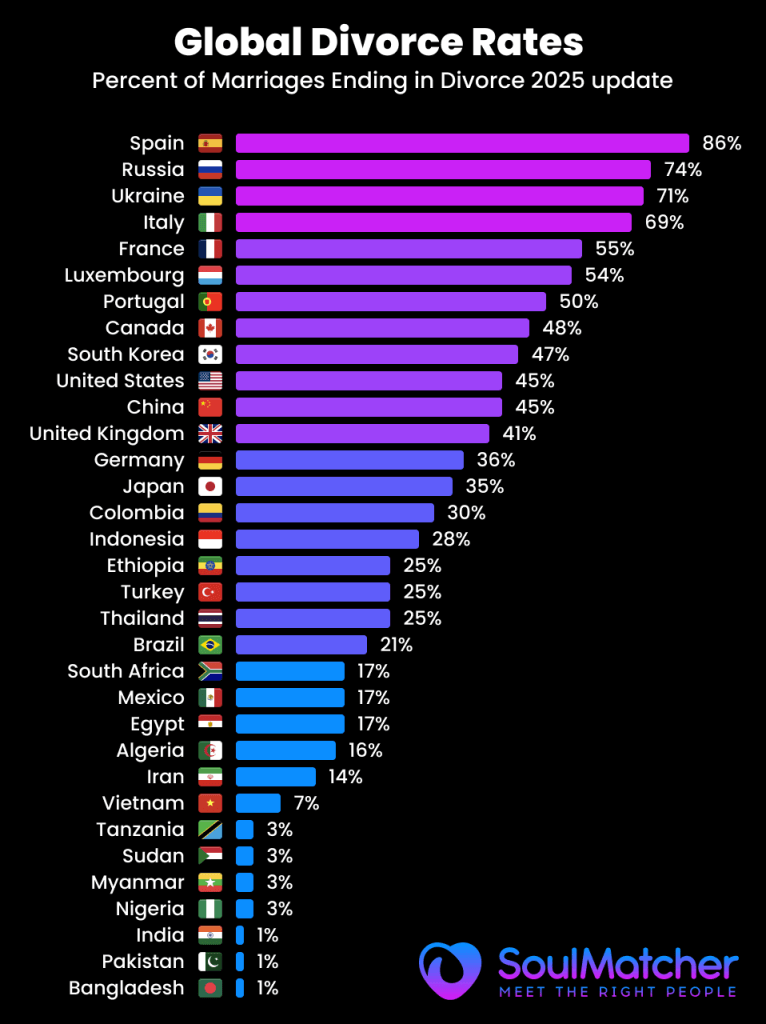

- Wide Global Range: In some countries nearly 0% of marriages end in legal divorce (e.g. the Philippines, where divorce is banned), while in others over 80% of marriages end in divorce (e.g. Portugal and Spain in recent years). Most nations fall between these extremes.

- Religious Restrictions vs. Secular Liberalization: Societies with strict religious prohibitions on divorce (e.g. Catholic or Hindu traditions) show very low divorce prevalence. Where religious influence has waned or laws have liberalized, even traditionally religious countries have seen divorce rates climb (for example, Catholic-majority Portugal’s divorce ratio spiked to ~94% in 2020).

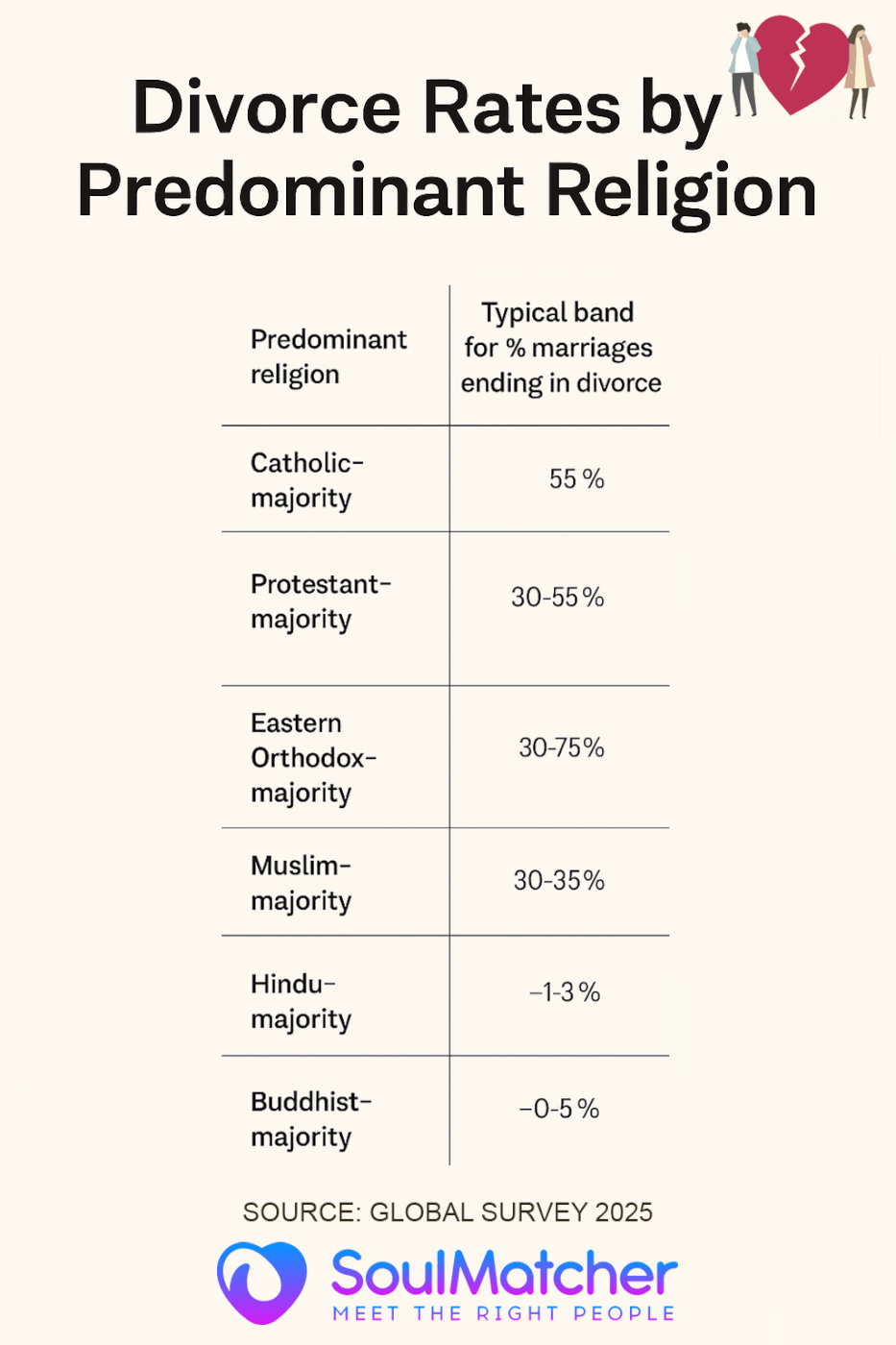

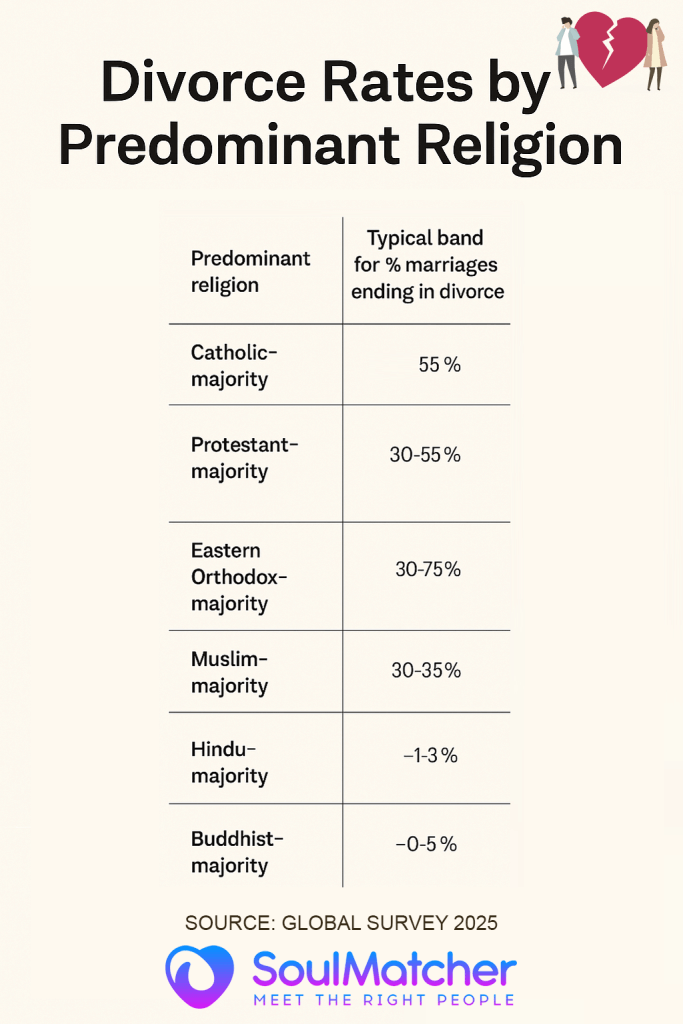

- Patterns by Faith: Muslim-majority countries generally report low-to-moderate divorce rates (often under 20%), Hindu-majority societies the lowest of all (~1%), and Catholic-majority countries historically low but now bifurcating – some remain low due to Church influence, while others rival the highest in the world after secularization. Protestant-majority and secular countries typically have moderate to high divorce rates (around 40–50%), reflecting greater social acceptance of divorce. Buddhist-majority countries show mixed outcomes, usually on the lower end unless influenced by modernization.

- Notable Outliers: Unique cases highlight how law and culture intersect with religion. For example, the Philippines (80% Catholic) is one of only two countries globally with no civil divorce, keeping its divorce rate effectively zero. By contrast, Portugal (also Catholic-majority) now tops global divorce rankings at over 90% of marriages ending in breakup. India’s Hindu society maintains an extremely low divorce rate (~1%) due to stigma, whereas Russia (Orthodox Christian heritage but secular outlook) has one of the highest divorce rates at ~74%. These outliers underscore that religious doctrine alone doesn’t dictate divorce prevalence – legal policies and societal change are decisive.

Below, Table 1 presents a snapshot of divorce-to-marriage ratios in selected countries alongside their predominant religion and data year, illustrating the stark global contrasts. This is followed by an in-depth comparison of divorce rates across major religious contexts and an analysis of underlying patterns.

Divorce Rates by Country and Predominant Religion

Table 1: Divorce-to-Marriage Ratio in Selected Countries (percentage of marriages ending in divorce, latest available year), with each country’s predominant religion for context:

| Country | Predominant Religion(s) | Marriages Ending in Divorce | Data Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portugal | Roman Catholic Christianity | 47% | 2023 |

| Russia | Eastern Orthodox Christianity | 73.6% | 2020 |

| United States | Christianity (Protestant majority) | 45.1% | 2020 |

| Turkey | Islam (Sunni Muslim majority) | 25.0% | 2018 |

| Egypt | Islam (Sunni Muslim majority) | 17.3% | 2010 |

| India | Hinduism | ~1% | ~2011 |

| Philippines | Roman Catholic Christianity | ~0% (divorce illegal) | 2024 |

| Thailand | Buddhism (Theravada Buddhist) | 25.5% | 2005 |

| Vietnam | Folk/Irreligious (Buddhist heritage) | 7.0% | 2015 |

| Czech Republic | No dominant religion (Secular) | 45.1% | 2018 |

Table 1: Divorce-to-marriage ratios illustrate how many divorces occur relative to new marriages in a given year, expressed as a percentage. (For example, 94% in Portugal means there were 94 divorces for every 100 marriages in that year.) This metric can spike when marriages drop (as seen in 2020 during COVID-19), so values above 100% are possible in rare cases. While not a direct lifetime divorce probability, this ratio is a useful snapshot of divorce prevalence. Below we examine these figures through the lens of predominant religions.

Catholic-Majority Countries

In countries where Catholic Christianity is the dominant faith, divorce has traditionally been rare – both because of religious doctrine and, historically, legal bans on divorce. The Catholic Church forbids divorce (marriage is deemed indissoluble) and only permits annulment in exceptional cases. Many Catholic-majority nations outlawed civil divorce well into the 20th century: for example, Italy (legalized in 1970), Portugal (in 1975), Spain (1981), Ireland (1996), Chile (2004), and Malta (2011) only recently allowed divorce by law.

This strong Catholic stance kept divorce rates extremely low for generations. Ireland and Malta still report some of Europe’s lowest divorce ratios after having legalized divorce relatively late. For instance, Ireland’s divorce-to-marriage ratio was about 15% as of 2017. In Malta, divorce was illegal until 2011; even by 2018 its ratio remained only ~12%.

However, secularization and legal change have led to sharply higher divorce rates in several Catholic-majority societies in recent decades. A striking example is Portugal, a country with an 80% Catholic population, which now has one of the world’s highest divorce proportions. In 2020, Portugal’s divorce-marriage ratio spiked to 94% – meaning almost as many divorces as marriages occurred that year. (This was exacerbated by a pandemic-related drop in weddings, inflating the ratio.) Even in more “normal” times, Portugal and its Iberian neighbor Spain (also predominantly Catholic) have very high divorce rates today – roughly 85% of marriages in Spain end in divorce according to recent data. This marks a dramatic shift from a few decades ago when these countries, under strong Church influence, saw minimal divorce. The change is attributed to liberalized divorce laws, declining religiosity, and changing social norms around marriage.

Other Catholic-majority countries show moderate divorce rates. For example, Poland (traditionally very Catholic) has a divorce-to-marriage ratio around 33%. This is lower than the European average, reflecting that many Polish couples still adhere to Catholic values that discourage divorce. Similarly, in Latin American nations with Catholic heritage – e.g. Mexico (~17% as of 2009) and Brazil (~21% as of 2009) – divorce rates have been rising but remain relatively modest. Many couples in these cultures choose informal separation or stay legally married even if estranged, due to the stigma of divorce in Catholic society.

A notable outlier is the Philippines, which is over 80% Catholic and prohibits divorce entirely by law (the only country besides Vatican City with such a ban). As a result, the formal divorce rate in the Philippines is effectively zero – marriages can only be ended via annulment or legal separation, which are rare. This legal strictness, rooted in Catholic doctrine, keeps the country’s divorce statistics among the lowest in the world. Culturally, marriage is considered sacred and for life. By contrast, Portugal – equally Catholic by demographics – shows how secular attitudes can override religious doctrine, as divorce has become commonplace there despite Church opposition.

Summary: Catholic-majority nations historically had very low divorce incidence due to religious and legal barriers. Where those barriers remain (Philippines, Malta until recently), divorce is exceedingly rare. But where Catholic societies have secularized and legalized divorce, their divorce rates have surged to some of the world’s highest (Spain, Portugal). The Catholic “divorce divide” is thus evident: adherence to traditional doctrine yields low divorce tolerance, whereas secular cultural shifts can result in divorce rates comparable to or exceeding those in non-Catholic societies.

Protestant-Majority Countries

Protestant Christianity generally holds a more permissive view of divorce than Catholicism, considering marriage a civil contract that can be dissolved under certain conditions (depending on denomination). Many Protestant-majority countries were among the first to establish civil divorce laws. As a result, divorce has been socially and legally accepted earlier in these societies, and their divorce rates have long been relatively high.

In the United States, where Protestant churches historically dominated, the divorce rate rose throughout the 20th century as social acceptance grew. The U.S. today has a national divorce-to-marriage ratio around 45% – roughly 45 out of 100 marriages end in divorce – which places it among the higher-divorce countries (19th highest out of 100 in one global ranking). Other nations with Protestant roots show similar figures: for example, Canada (48% of marriages end in divorce) and the UK (~41% as of mid-2010s) are in the same range. In Northern Europe, traditionally Protestant but now very secular, divorce rates hover around 40–50% as well. Sweden, for instance, has about 50% of marriages eventually ending in divorce, and Denmark about 55% – among the highest in Europe. These high rates reflect not only lenient divorce laws (e.g. no-fault divorce) but also liberal social attitudes that view divorce as an acceptable solution to marital breakdown.

It’s worth noting that within Protestant-majority countries, religiosity still matters to some extent. In the U.S., for example, highly religious Protestant communities (such as certain evangelical groups) often have somewhat lower divorce rates than the national average, whereas more secular or culturally liberal regions have higher rates. Nonetheless, the differences are modest – even the most religious U.S. states have significant divorce levels, partly due to earlier marriage ages and other socio-economic factors. Overall, marriage dissolution is fairly common and broadly tolerated in Protestant-influenced cultures compared to societies with more prohibitive religious norms.

Historically, Protestant reformers in Europe (16th century onward) positioned marriage as a contract rather than a sacrament, which opened the door for civil divorce. This ideological shift set Protestant societies on a path to normalize divorce much sooner. By the 20th century, countries like the UK and Scandinavia had established legal divorce procedures while Catholic nations still banned it. This legacy is evident in today’s statistics – the Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway), with Lutheran Protestant heritage, consistently report divorce ratios around 45–55%. The United Kingdom likewise sees roughly 40–42% of marriages ending in divorce in recent years.

In summary, Protestant-majority countries typically exhibit moderate to high divorce rates (around 1 in 2 to 1 in 3 marriages ending). Divorce is broadly accepted as a regrettable but normal part of life in these societies. Religious teachings in mainline Protestant denominations generally discourage divorce but allow it in cases of broken marriages (adultery, abuse, irreconcilable differences, etc.), which has aligned with more permissive civil laws. Consequently, the cultural stigma is lower and couples are more willing to legally part ways compared to their Catholic or Hindu counterparts. It’s important to note that secularization in these countries has further reduced any religious barrier – many people are non-practicing, so religious disapproval plays little role in their personal divorce decisions.

Eastern Orthodox-Majority Countries

Eastern Orthodox Christianity (practiced in countries like Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Greece, Serbia, etc.) traditionally occupies a middle ground on divorce: the Orthodox Church views marriage as sacred but permits divorce under certain circumstances (unlike Catholicism which outright forbids it). Historically, the Eastern Orthodox Church has allowed up to two or three remarriages for individuals, considering divorce acceptable in cases such as adultery or abandonment, albeit with a penitential character. This somewhat more lenient stance, combined with various cultural and political factors, has yielded mixed outcomes in Orthodox-majority nations.

Slavic and post-Soviet states with Orthodox majorities now have some of the highest divorce rates in the world – largely due to secularization and social upheaval during the 20th century. For example, Russia, which is culturally Russian Orthodox (over 70% identify with Orthodoxy), has a national divorce rate of about 74%. More than three-quarters of Russian marriages end in divorce, according to recent data, putting Russia at or near the top globally. Similarly, predominantly Orthodox Ukraine had a divorce ratio around 71% in 2020. Belarus (Orthodox majority) also shows a high rate – around 60–65% of marriages ending in divorce in recent stats. These figures reflect not so much religious teaching, but the legacy of communist-era secular policies, economic stress, and changing family norms. Under the Soviet Union, divorce was made very accessible early on, and although policies fluctuated, by the late 20th century most of these societies had relatively normalized divorce. The trend has continued, with contemporary Russia and its neighbors experiencing high marriage turnover. As one report notes, the divorce rate in Russia implies “more than three-quarters of all marriages end in a breakup”, a statistic attributed to economic instability and shifting social values rather than Orthodox doctrine.

On the other hand, some traditionally Orthodox countries with stronger religious influence or different socio-economic conditions show lower divorce rates. For instance, Greece (Greek Orthodox majority) has a divorce-to-marriage ratio of roughly 38% – lower than the European average, perhaps due to more traditional family structures and the Church’s influence (the Orthodox Church in Greece discourages divorce despite permitting it). Serbia likewise had about 27% of marriages ending in divorce as of 2018, a moderate level. These are still higher than many Muslim or Hindu societies but notably lower than the more secularized Orthodox countries to the north.

In summary, Orthodox-majority societies do not present a single pattern: the most secular ones (e.g. Russia, Belarus) have divorce rates on par with the highest in the world, whereas more religious or traditional Orthodox communities (e.g. Greece) keep divorce at moderate levels. Orthodox Christianity’s allowance for divorce in principle means there is less absolute religious barrier than in Catholicism. Thus, local culture and history play a larger role – the extreme post-Soviet divorce rates speak to social and economic dynamics (urbanization, alcoholism, poverty, changing gender roles) in those countries, more than theology. Where Orthodoxy remains a strong social force, it helps maintain somewhat lower divorce incidences, emphasizing reconciliation and the seriousness of marriage even though divorce is not outright forbidden.

Muslim-Majority Countries

In Muslim-majority countries, divorce is generally permitted in religious law (Sharīʿa), but the prevalence of divorce varies widely with cultural norms and legal frameworks. In Islam, marriage is a contract and divorce (ṭalāq), while allowed, is often described as “hated by God” when done capriciously. Traditional Islamic practice makes divorce easier for husbands (who can repudiate a wife) than for wives, though many countries have reformed laws to be more equitable. Socially, many Muslim cultures stigmatize divorce, especially for women, which has historically kept divorce rates low. That said, the legal ability to divorce has always existed in these societies, so when social or economic conditions change, divorces can and do happen with less religious obstacle than in Catholic or Hindu contexts.

Overall, many Muslim-majority nations today report low divorce-to-marriage ratios – often under 20%. India’s Muslim community (though India is Hindu-majority, it has a large Muslim population under personal law) has a relatively low divorce incidence, and Muslim-majority neighbors like Bangladesh and Pakistan similarly see few divorces in proportion to marriages (exact figures are hard to come by, but indications are in the single-digit percentages). For a concrete example, Tajikistan (over 90% Muslim) had about a 10% divorce ratio in 2009. Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim country, traditionally also had very low divorce rates, though they have inched up in recent years with greater women’s rights and urbanization (still, divorce remains far less common there than in the West).

Arab countries tend to exhibit low to moderate divorce rates. Egypt, for instance, is a predominantly Muslim society where only 17% of marriages ended in divorce as of 2010. Marriage is strongly valued and family pressure to avoid divorce is high, despite divorce being legal (Egypt has even seen some increase in divorces in the past decade, but rates are still modest). Jordan and Lebanon had divorce ratios around 26–27% in recent data – higher than South Asia or Southeast Asia, but still relatively low by global standards.

However, there is considerable variation. Some Muslim-majority countries that are more secular or economically developed show higher divorce prevalence. Turkey, for example, though 99% Muslim by population, is a secular republic with relatively liberal family laws. Turkey’s divorce-to-marriage ratio is about 25% (1 in 4 marriages ending in divorce), which is higher than in most of the Middle East but still half the level of the U.S. or Europe. Kazakhstan, a culturally Muslim but secular Central Asian country, has a divorce rate of roughly 34%. In the Central Asian region, Soviet influence made divorce socially acceptable to a degree – hence Kazakhstan, along with Moldova (which has a large Muslim minority) and others, appear in the mid-range of global divorce rates (30–40%).

The Gulf States present another interesting case. In places like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the UAE, divorce rates have been rising as these societies modernize. Saudi Arabia’s divorce-marriage ratio was reported at 37.5% in 2020 – surprisingly high given its conservative reputation. This could be due to the ease of pronouncing ṭalāq and evolving attitudes among younger couples in urban centers. Similarly, Qatar had about a 33% ratio (2011 data). On the other hand, more traditional Gulf societies like Oman or Yemen still likely have lower rates (data is sparse, but anecdotal evidence suggests divorce is less common where extended family structures are strong).

One extreme outlier in the Muslim world has been the Maldives – a small island nation that historically had one of the highest crude divorce rates globally (multiple marriages and divorces were culturally common, especially among women). Though Maldives’ divorce-to-marriage ratio is not listed in Table 1, it has been noted as exceptionally high in the past (Maldives once recorded 5.5 divorces per 1,000 people – the world’s highest crude rate), reflecting very different local customs despite being 100% Muslim.

Summary: Most Muslim-majority countries maintain low divorce rates in line with Islamic teachings that, while allowing divorce, encourage couples to stay married. Stigma and family pressures contribute to keeping divorce uncommon (e.g. South Asia, much of the Arab world). Where modernization, urbanization, and legal reforms have taken hold – such as Turkey, parts of Central Asia, and the Gulf – divorce is becoming more prevalent but still generally falls below Western levels. Islam’s relative flexibility on divorce (compared to Catholicism or Hinduism) means that when social conditions permit, divorces can occur without religious impediment. Yet, in practice, traditional values in Muslim societies often act as a brake on divorce, resulting in significantly lower rates than in equally modern but more secular societies. The pattern is not monolithic: factors like women’s education, economic independence, and government laws (e.g. availability of khula for women) lead to a spectrum of divorce prevalence in the Islamic world.

Hindu-Majority Countries

Hinduism places a strong cultural emphasis on the permanence of marriage. In traditional Hindu philosophy, marriage (vivaha) is a sacred, lifelong union – “until death” – and there historically was no concept of divorce in classical Hindu law. While modern legal codes (like India’s Hindu Marriage Act, 1955) do allow for divorce, the stigma around divorce in Hindu-majority societies remains extremely high. As a result, the percentage of marriages that end in divorce is the lowest in the world in Hindu-dominant countries.

The clearest example is India, home to the vast majority of the world’s Hindus. India’s divorce rate is famously low – roughly 1% of marriages end in divorce, according to various studies and statistics. In global rankings, India consistently has the lowest divorce rate; one analysis noted “India has the lowest divorce rate – only 1%”. This is despite India having legalized divorce for Hindus for over 60 years. The low number reflects that, socially, divorce is often seen as a last resort and carries social shame, especially for women. Many Indian couples remain married even in unhappy situations due to familial pressure, concern for children, and the cultural value placed on lifelong marriage. Arranged marriages, still common, often come with strong family involvement to help couples stay together.

Other Hindu-majority or influenced societies show a similar pattern. Nepal, which is predominantly Hindu, also has an extremely low divorce rate (exact figures are hard to find, but presumably only a few percent of marriages end in divorce). Sri Lanka, while Buddhist-majority, has a large Hindu minority and a similar South Asian cultural outlook – it boasts one of the world’s lowest crude divorce rates at about 0.15 per 1,000 people, implying a very small fraction of marriages break up (on the order of just 1–2%). In these cultures, divorce is often viewed as a failure of duty and is discouraged by community norms.

It’s important to note that legal and economic factors also play a role. In India, obtaining a divorce through the courts can be a lengthy and cumbersome process, which deters many. Women’s economic dependence on husbands, especially in rural areas, also keeps divorce rates low (as leaving a marriage might not be financially viable). Additionally, alternative solutions like informal separation or living apart without formal divorce sometimes occur but are not reflected in statistics – the couple remains legally married.

Tolerance for divorce is gradually changing among urban, younger Hindus, but from a very low base. In Indian metros, attitudes are slowly liberalizing and divorce is becoming a bit more common (particularly in cases of abuse or mutual incompatibility), but even in cities the rates are low compared to global norms. Surveys by Pew Research indicate that Indians across faiths continue to view divorce negatively; marriage is often seen as an unbreakable commitment.

In summary, Hindu-majority societies have the strongest cultural resistance to divorce, resulting in the lowest divorce prevalence globally. With ~1% or so of marriages ending in divorce in India, marriage is nearly universal and almost always permanent until widowhood. This reflects both deeply ingrained social values – influenced by Hindu beliefs in familial duty and karma – and practical barriers. As social norms evolve and women become more empowered, divorce may inch upward, but in the foreseeable future Hindu cultures are likely to retain very low divorce rates relative to the rest of the world.

Buddhist-Majority Countries

Buddhist teachings do not explicitly forbid divorce in the way Catholic doctrine does; marriage in Buddhism is seen more as a social contract than a religious sacrament. The religion places emphasis on harmony and reducing suffering, so while divorce is allowed, it is ideally avoided if it causes suffering. In practice, Buddhist-majority countries display moderate to low divorce rates, influenced largely by local traditions and legal structures rather than religious prohibition.

In South and Southeast Asia, many Buddhist-majority societies historically had low divorce rates, partly due to conservative social norms and patriarchal family structures. For example, Sri Lanka (70% Buddhist) has an extremely low divorce incidence – as noted, its crude divorce rate is around 0.15 per 1,000 people, which corresponds to only a tiny percentage of marriages ending in divorce (on the order of 2–3%). Marriage is highly valued in Sri Lankan culture, and although divorce is legal, it is relatively uncommon and stigmatized. Myanmar (Burma) and Thailand, both predominantly Buddhist, traditionally also emphasized stable marriages, though Thailand stands out as an exception with higher divorce figures in recent decades.

Thailand is a Buddhist-majority country that has seen divorce become more frequent as it modernized. As of the mid-2000s, Thailand’s divorce-to-marriage ratio was about 25% (one in four marriages ending in divorce), which was high by Asian standards (though lower than Western rates). This suggests that while Buddhism as a religion isn’t a barrier, Thai cultural norms (which are relatively liberal in some respects) allowed more marital dissolution. Still, Thailand’s ~25% is far below the ~50% seen in parts of Europe/America. Other Southeast Asian countries with Buddhist influence, like Vietnam, maintain very low divorce rates – Vietnam’s ratio was around 7% in 2015, reflecting the strong Confucian family values and perhaps the socialist government’s promotion of family stability. Vietnam is officially secular/atheist in governance, but culturally many are influenced by Buddhist and Confucian traditions that emphasize family cohesion, which likely contributes to the low divorce rate (7% is among the lowest globally after India).

In East Asia, where Buddhism mixes with other philosophies, we see moderate divorce rates. Japan and South Korea are not majority Buddhist (they are religiously mixed, with Buddhism and Christianity and secularism), but they have Buddhist heritage. Japan’s divorce rate is about 35% (for marriages in recent years) – a moderate level. South Korea’s is closer to 47% as of 2019, which is relatively high and comparable to Western nations. These East Asian cases show that as societies industrialize and individualize, divorce becomes more common even without a strong religious taboo; Buddhist or Confucian ideals alone didn’t prevent rising divorces once social conditions changed. However, the rates in Japan and Korea are still somewhat below the peaks seen in places like the U.S. or Russia, possibly due to lingering cultural expectations around marriage and the family.

Broadly, Buddhist-majority countries do not exhibit the extremely low divorce levels of Hindu or strictly Catholic ones, but they also avoid the very high levels seen in the secular West or post-Soviet states – unless other factors push them up. The typical range might be 5–30% of marriages ending in divorce. Cambodia and Laos, for instance, are Buddhist societies with relatively traditional rural populations; their divorce rates are presumed low (exact stats are scarce, but likely under 10%). Bhutan (Mahayana Buddhist kingdom) similarly values marriage and has low divorce occurrences, though data is limited.

In summary, Buddhism’s influence on divorce is indirect – the religion neither bans nor encourages divorce, so the outcomes depend on local culture and law. Many Buddhist cultures emphasize harmony, social order, and the family unit, which tends to keep divorce rates on the lower side. Where modernization and Westernization have taken root, as in Thailand or urban East Asia, divorce rates have risen accordingly, but generally Buddhist regions still report fewer divorces than comparably developed non-Buddhist regions. The case of Thailand (~25%) versus secular Europe (50%+) or China (44%) illustrates that something in the cultural fabric – possibly Buddhist-influenced values or community pressure – may moderate the extent of marital breakdown.

Secular and Non-religious Societies

In countries where no single religion is dominant or where society is highly secular, divorce rates tend to be on the higher end, driven more by socio-economic factors and personal choice than by religious constraints. Secular societies often prioritize individual happiness and autonomy, viewing marriage as a personal contract that can be ended if it no longer works for the individuals involved. Without a strong religious stigma, divorce becomes more of a normalized life event.

One category here are the post-Communist countries where religion was suppressed for decades, leading to largely secular populations. For example, Czech Republic is one of the most non-religious countries in the world (over 70% non-affiliated), and it has a high divorce-marriage ratio of about 45%. Similarly, the Baltic states and Central European countries that are highly secular report divorce rates in the 40–50% range (e.g. Estonia ~48%, Latvia ~46%, Hungary ~33–35%). These rates align with their European neighbors and reflect that once divorce lost its taboo, roughly half of marriages in secular societies may eventually fail due to the universal pressures of modern life (economic stress, shifting gender roles, reduced social pressure to stay married, etc.).

Another example is China, where traditional religion plays a lesser role in policy (officially atheist state, though culturally influenced by Confucian and folk practices). China’s divorce-to-marriage ratio has climbed significantly in recent decades, reaching about 44% by 2018. Rapid urbanization and legal reforms (China made divorce easier in the 2000s) led to a spike in divorces. In fact, China saw divorces quadruple between the 1980s and 2010s as the stigma eroded. While Confucian family values still exert some influence, younger generations are increasingly open to divorce. The Chinese government even grew concerned about rising divorce rates and implemented a “cooling-off” period in 2021 for couples filing for divorce. Nonetheless, China’s example shows that without strong religious discouragement, a country can move from very low to fairly high divorce prevalence within a generation.

Western Europe has largely become secular, even if populations nominally identify as Christian. As a result, many West European countries have high divorce ratios regardless of historical religion. For instance, France (historically Catholic but highly secular now) has about 51% of marriages ending in divorce. Belgium (~54%) and the Netherlands (~49%) are similar. Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland) are often cited as among the most secular societies; they also have some of the highest divorce proportions (about 50–55%, as noted earlier). Even Luxembourg, a small secularized Catholic country, had the highest divorce ratio in Europe in 2019 (around 79% of marriages ending in divorce). This underscores that when religious adherence fades, other factors like economics, laws, and cultural acceptance become decisive – and those have generally trended toward higher divorce in affluent secular nations.

It is interesting that not all secular or non-religious societies have high divorce rates – some maintain low rates due to cultural reasons unrelated to formal religion. Vietnam is an example: despite low formal religiosity, its strong Confucian family culture keeps divorce very low (~7%). Another example could be Guatemala, which, while traditionally Catholic, has many who practice folk religion and it’s somewhat secular in governance; Guatemala reports a low divorce risk (it was listed among countries with “low risk of ending in divorce” along with Vietnam and Malta). This suggests “secular” is not automatically synonymous with high divorce – the presence or absence of a strong alternative cultural norm is key. In Vietnam’s case, the norm is family unity and social harmony; in contrast, in places like Czech Republic or France, individual choice is prioritized, yielding higher divorce acceptance.

In sum, secular countries typically experience higher divorce rates, as decisions are less constrained by religious injunctions. People in these societies are more likely to leave unsatisfactory marriages, and legal systems make it relatively easy to do so (no-fault divorce, etc.). The highest divorce ratios on record (Portugal’s ~94%, Spain’s ~85%, Russia’s ~74%) have all occurred in environments where religion has minimal say in personal life. That said, secularism interacts with culture: some secular societies with strong family-centric cultural values may not reach Western levels of divorce. Overall, though, the global pattern is clear – when a society becomes more secular and modern, divorce loses its taboo and the percentage of marriages ending in divorce tends to rise significantly.

Conclusion: Religion and Divorce – Patterns and Exceptions

Globally, the relationship between predominant religion and divorce prevalence is evident but not absolute. Religious doctrines set the tone – for example, Catholic and Hindu teachings strongly discourage divorce, correlating with very low divorce rates in places like the Philippines and India. In contrast, Protestant and secular ethics accept divorce, aligning with higher rates (~40–50% in much of Europe and North America). Islamic societies fall in between: divorce is religiously allowed but socially moderated, yielding mostly low rates with some rising trends. Buddhist-influenced cultures also generally have low-to-moderate divorce incidence.

However, secularization and legal changes can override religious tradition. Notable examples are Catholic-majority countries like Portugal and Spain now leading in divorces, and Orthodox countries like Russia experiencing very high divorce levels despite religious conservatism on paper. These cases show that economic factors, legal ease of divorce, urbanization, and changing social values can dramatically shift divorce patterns even in traditionally religious societies.

In contrast, legal barriers (as in the Philippines) and enduring social stigma (as in India and many Muslim communities) can keep divorce rates extremely low despite modernization. Each country’s divorce rate thus results from a combination of its predominant religion’s teachings, the strength of religious adherence, civil divorce laws, and broader cultural attitudes toward marriage.

In summary, religion plays a powerful role in setting the normative “tolerance” for divorce – with more conservative faiths linked to less divorce – but it is not destiny. As the world becomes more interconnected and values shift, some traditionally low-divorce societies may see increases, while policies and social initiatives can also help stabilize marriages in high-divorce areas. The current global landscape shows both adherence to age-old religious marital ideals and rapid transformations where those ideals give way to new norms. The interplay of religion and divorce will continue to evolve, but understanding these patterns helps explain why in some countries virtually no marriages break up, while in others a young couple’s “till death do us part” has roughly even odds of lasting a lifetime or ending in court.

Takeaways

Divorce laws and social norms vary widely around the world, and predominant religious traditions play a significant role in these differences. Countries with strong religious influence – for example, where Catholicism or Islam is prevalent – often show markedly lower divorce rates, whereas more secular or Protestant-majority societies tend to have higher divorce incidences. Of the nations with the very lowest divorce rates globally, many are predominantly Catholic, Muslim, Hindu, or Buddhist, underscoring the impact of religious and cultural values. By contrast, in more secular or historically Protestant countries, divorce is relatively common and socially accepted – for instance, about 39% of couples in the United States end up divorcing. Below is a breakdown of divorce rate patterns in countries grouped by their majority religion, with representative examples and trends for each.

Catholic-Majority Countries

Catholic doctrine historically forbids divorce, and this has translated into strict laws or social stigma against divorce in many Catholic-majority nations. As a result, these countries have generally had very low divorce rates. For example, Ireland and Italy – both traditionally Catholic – long recorded some of Europe’s lowest divorce figures. Malta, a deeply Catholic country, did not even legalize divorce until 2011; it still has the lowest divorce rate in the EU at only about 0.8 divorces per 1,000 people. Several Latin American countries with Catholic majorities likewise show low rates: Chile only introduced divorce in 2004, and its rate remains very low (on the order of 0.9 per 1,000 people, roughly 3% of marriages). In Colombia and Mexico, culturally Catholic values have traditionally kept divorce uncommon (historically under 10–15% of marriages), though rates have risen as legal and social attitudes liberalize. Overall, predominantly Catholic societies emphasize the permanence of marriage, and divorce often carries social disapproval, contributing to these low national divorce rates.

Protestant-Majority (and Secular) Countries

In countries where Protestant denominations are common – as well as in broadly secular Western societies – divorce tends to be more frequent and socially accepted. Protestant Christianity generally permits divorce under certain conditions, and over time many of these societies developed more liberal divorce laws (e.g. no-fault divorce) and a culture that views divorce as a personal choice. Consequently, crude divorce rates in Protestant-majority nations are among the highest globally, typically around 2–3 divorces per 1,000 people annually. For example, the United Kingdom reports roughly 1.9 divorces per 1,000 people, and Northern European countries like Sweden reach about 2.5 per 1,000. The United States (historically majority Protestant, though religiously diverse) has a similarly high incidence – about 2.4 divorces per 1,000 people, which corresponds to roughly 39% of marriages ending in divorce. High divorce rates in these countries are often linked to more individualistic and secular attitudes toward marriage, greater economic independence (especially for women), and fewer religious or legal barriers to ending unhappy unions. In summary, predominantly Protestant or non-religious societies generally see moderate to high divorce rates, reflecting cultural acceptance of divorce as a normal life decision.

Muslim-Majority Countries

Most Muslim-majority countries traditionally exhibit low to moderate divorce rates, although Islamic law does permit divorce. Social and religious norms in many Islamic cultures strongly discourage breaking up the family unit, which historically kept divorce less common. For instance, conservative Muslim societies in South Asia and the Gulf have reported crude divorce rates well below 1 per 1,000 people. Qatar, for example, has a divorce rate of about 0.7 per 1,000, one of the lowest globally. These low figures are often attributed to stigma around divorce, family pressure to remain married, and legal hurdles (e.g. requirements for mediation or waiting periods in some Sharia-based family courts). However, there is considerable diversity in the Muslim world, and some countries are seeing rising divorce levels. Urbanization, changing gender roles, and legal reforms have led to higher divorce outcomes in parts of the Middle East. Notably, in countries like Kuwait and Jordan, roughly 35–48% of marriages now end in divorce – a rate comparable to Western nations. One striking outlier is the Maldives (also Muslim-majority), which has the highest divorce rate in the world at about 5.5 divorces per 1,000 people. In the Maldives, relatively easy divorce procedures (e.g. the tradition of “triple talaq”) and serial remarriages contribute to this unusually high rate. In summary, while Islamic teachings value stable marriage (and many Muslim-majority countries accordingly have low divorce rates), modernization and differing local practices cause a wide spectrum – from some of the world’s lowest divorce rates to rates approaching the global highs.

Hindu-Majority Countries

Divorce is exceedingly rare in Hindu-majority societies. The cultural and religious ethos in Hinduism places a strong emphasis on the sanctity of marriage – marriages are often seen as not only a social contract but a sacred bond that is expected to last a lifetime. In India, the world’s largest Hindu-majority country, the divorce rate is famously low: only around 1% of marriages end in legal divorce. This translates to a minuscule annual divorce rate (on the order of 0.1–0.2 per 1,000 people, the lowest in the world). Such low figures are sustained by strong social stigma against divorce, extended family influence, and the prevalence of arranged marriages which are guided by familial and societal compatibility expectations. Even when marital discord exists, many couples in India (and in other Hindu-majority nations like Nepal) opt for informal separation or endure unhappy marriages rather than go through legal divorce, due to the cultural pressures. Legal obstacles also play a role – historically, Indian divorce law required showing fault (adultery, cruelty, etc.), which set a high bar. The net effect is that Hindu-majority countries consistently report the world’s lowest divorce rates, with traditional norms and family structures discouraging marital dissolution.

Buddhist-Majority Countries

Countries with predominantly Buddhist populations also tend to have low divorce rates, although this is influenced more by culture and law than by explicit religious prohibitions. Buddhism does not forbid divorce outright, but it emphasizes harmony, tolerance, and the resolution of conflict, which can translate into social expectations to keep marriages intact. Additionally, many Buddhist-majority nations share cultural values (often intertwined with Confucian or local traditions) that highly value family unity and stability. For example, Sri Lanka, a largely Buddhist country, currently has one of the lowest divorce rates globally at only ~0.15 per 1,000 people. Sri Lanka’s laws require proving fault (such as infidelity or abuse) to get a divorce, which makes the process difficult and helps keep the rate low. Similarly, Vietnam (where Buddhism and folk religions are prevalent, alongside a notable Catholic minority) has an extremely low rate around 0.2 per 1,000. In many Southeast and East Asian societies influenced by Buddhism – such as Myanmar, Thailand, and Singapore – divorce was traditionally uncommon, though it has become more frequent with modernization (for instance, Thailand’s divorce rate has risen in recent decades with changing social norms). It’s noteworthy that cultural and legal factors (family pressure, social stigma, and challenging divorce procedures) are key to the low divorce numbers in these countries, rather than Buddhist doctrine alone. Overall, predominantly Buddhist countries generally align with the pattern of religiously traditional societies having lower divorce prevalence than the global average.

Global snapshot: Divorce rates by predominant religion. Catholic-, Muslim-, Hindu-, and Buddhist-majority countries tend to have much lower divorce rates (often below 1 per 1,000 people annually) compared to Protestant-majority or secular societies. Each country’s legal framework and cultural attitudes – often shaped by religion – play a major role in these outcomes. (No data from the Philippines is included in this comparison.)

Conclusion

Across the globe, there is a clear correlation between predominant religion and divorce rates. Societies rooted in faiths that discourage divorce (Catholicism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism) often report significantly fewer divorces. These low rates are reinforced by legal barriers (such as requiring proof of fault or long separations) and social stigmas against divorce in those cultures. On the other hand, countries with more permissive attitudes – frequently those with Protestant or secular majorities – see higher divorce rates, reflecting a view of marriage as a reversible contract and the greater social acceptability of ending an unhappy marriage. It is important to note, however, that religion is just one factor. Economic development, urbanization, education, and gender equality also influence divorce patterns. In summary, while predominant religion sets the tone – whether through doctrine or culture – for how marriage is valued, the reality of divorce in any country results from a complex interplay of religious norms, laws, and modern social change.

Sources:

- National and international statistical reports on marriage & divorce (UN, Eurostat, national censuses)

- Pew Research Center and World Religion Database (religious demographics and societal attitudes)

- Analysis by CasinoAlpha data scientists on global divorce odds and news reports (Statista, Yahoo News) highlighting record-high divorce ratios in Europe (e.g. Portugal, Spain)

- Academic and legal studies on religion and divorce practices.