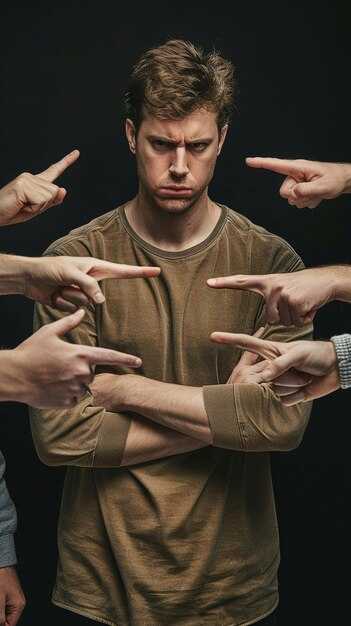

Severe neglect in childhood — when adults consistently fail to meet your needs — can create an emotional fragility that follows you into adulthood. Even if you build a comfortable life and pursue goals, many people with complex PTSD report feeling disconnected from others despite apparent closeness. The lingering memory of being uncared for can infiltrate every relationship: with dates, friends, coworkers, classmates. If that wound remains unaddressed, it paradoxically drives you toward—and keeps you in—relationships where your needs are ignored. That pattern can be changed; it’s possible to heal. Today’s letter comes from a young man who will be called James. He writes: Dear Fairy, I’m tangled up in issues with close friends and I don’t know if these friendships can be repaired or if I should cut them off completely. Alright, the fairy pencil is out and I’ll note the parts to revisit, but let’s unpack James’s situation. I’ve always been shy, which I think began because I was left alone a lot when I was small. When I was born my father worked across the country and only came home every two weeks if we were lucky — that was rough. My mother worked as a diner cook with long morning and evening shifts and a small break in the afternoon — also rough. Mostly, my maternal grandparents looked after me, but that wasn’t ideal either: my grandfather, a construction worker, was gone all day and at night showed the worst side of himself as an alcoholic. The only person who gave me some attention was my grandmother, a seamstress who unwound after work by watching TV or sewing and preferred not to be disturbed. So essentially I was neglected. This continued until I was five and my younger brother was born. We moved out of my grandparents’ house into our own place. My mother took time off work so I expected more attention — but I ended up even less relevant. My complaints became a nuisance; I grew resentful and withdrew from the family. A year later another brother arrived, and I was simply expected to help and obey. My teenage years were a kind of hell and I had a breakdown during my first year at university. After some time off, I’m now near graduation. It was hard to sustain myself financially and this final push feels crushing. Each day I work harder hoping this next effort will shift the boulder up the hill and finally ease things. Of course this strain affected the few friendships I had. Many of my friends are as stuck as I was at the beginning of my journey; now that I’ve progressed even a little, it frustrates me that most of them insist their problems are unsolvable or that improvement is impossible — yet they don’t try anything I’ve suggested. That’s why I feel they’re bad influences who could keep me trapped in a negative way of thinking, but I also dread losing them. I care about each of them; we share experiences and time. Even though they clearly don’t reciprocate the care I give — nobody checks in on me while I check on them weekly — I still sense they care in their own way. I’m not sure if that’s reason enough to let them go. Another huge barrier is they’re interlinked with most of my other friends, so cutting them off might ripple through my entire social circle and leave me with almost no friends — only distant acquaintances outside this group. I don’t know what to do; I feel trapped. In the past when I felt like this I withdrew, handled my feelings alone, and later returned to the group. But I don’t think that’s healthy. I fear loneliness because I know it can be damaging. Deep down I don’t feel cared for — that’s the core. Being with them and feeling ignored hurts, but being alone also hurts. I can’t escape it short-term; what should I do long-term? I’m terrified of having to make new friends because I worry people will sense my neediness and pull away. I also feel somehow responsible for this situation even though I logically know I tried to improve these relationships and find new friends; it just doesn’t feel like my fault. I keep feeling like the child nobody wanted. Thanks for your help. I hope you reach out again. Okay James, let’s examine what’s happening. What’s powerful here is that when people share a mutual experience, someone currently less entangled can offer perspective — and that’s what makes it so brave to reach out. The feelings you describe are very familiar. There’s often an age-related pattern: breakdowns commonly arrive in college or just after, when you’re away from home and life is both unstable and demanding. People frequently contact me during or after that type of crisis because being out on your own brings the wound into focus. When the parents no longer actively hurt you every day, the wound remains and becomes recognizable, and that’s actually a hopeful thing: internal states are easier to change than the past actions of others. Trying to make the people who raised you act differently is usually futile; you can’t reliably change their behavior. But you can heal the part of yourself that was hurt. You showed excellent self-awareness by naming how unbearable it feels to finish college under these conditions. Doing something tough when you were deprived of emotional support as a child — working through college while supporting yourself — requires extraordinary determination and self-denial. Give yourself credit: you are surviving, and that’s something to be proud of. Regarding your friends: you didn’t describe specifics, but it sounds like they lack a healing mindset. You have developed self-awareness and see a need for growth; they may have compartmentalized their pain and not faced it yet. People who avoid their trauma often manage to keep it hidden for a while, but it can resurface in late twenties or early thirties when life demands more authenticity. As you grow, you naturally outgrow some friends; healing commonly results in losing certain relationships. Some friends remain because of affection and mutual tolerance; others drift away because your changes make them uncomfortable. You may already have seen pushback — people can resent someone trying to heal, thinking “oh, Mr. Healer here, you think you’re better than me.” If your friends are focused on partying or repeating destructive patterns, and that bothers you, you can’t force them to change. The most effective influence you have is to change yourself in positive, visible ways. Seeing you transform often inspires others more than arguments or advice. For now, your self-awareness, reaching out, and connecting with people (including thousands who may see your story) are important. You’re not alone and you will meet people who match your new level of recovery; the right new friends tend to arrive more quickly the less you cling to people who generate conflict. That said, staying compassionate and keeping some friendships out of fondness is honorable. You can choose differently for each friend — some relationships are worth maintaining, others not. Soon you’ll leave school and that transition will open opportunities to meet new people. It will go better if you continue processing your emotions and avoid self-sabotaging thoughts like “I shouldn’t have healed” or “Who do I think I am?” When you lose friends you may doubt yourself; building casual connections with others who are also healing can give you social anchors. In transitional phases, groups are especially helpful. Twelve-step communities are often a refuge: many members are sincerely working on themselves, there’s a culture of friendliness and mutual support, and you can find people trying to improve who become good friends. Other options include sports, martial arts, theater groups, therapy groups, or supportive membership programs that provide courses, discussion groups, and regular meetings. Those environments let you meet people who are actively learning and growing together. Early trauma can disrupt the neural and social patterns that allow secure connection, but it’s something you can change. Cultural norms like casual sex can make attachment wounds worse by tempting people to trade real intimacy for immediate, superficial contact. For those with neglect histories, the attachment wound longs for someone to stay; casual, non-committal encounters encourage sacrificing that longing for temporary closeness. Healing means letting yourself want real love and creating conditions where it can grow: slow, honest communication, emotional regulation, and authentic self-protection instead of rushing to fit someone else’s terms. My next letter is from a woman called Nora. She writes: Dear Fairy, I’m 38 and have CPTSD from growing up in a verbally abusive and emotionally neglectful family. I’ve learned tools for self-regulation over several years, but an incident ten days ago left me shaken and depressed. I dated a man for a month whom I met at a New Year’s Eve party. From the beginning I noticed red flags but ignored them: I pursued him more than he pursued me; he was vague about feelings and plans and explicitly said he wanted to keep things casual. Two weeks after New Year’s we spent a long weekend together and slept together. I told him I have anxiety and abandonment issues and that I’m working on them; he seemed understanding. Still, his low level of pursuit and some hot-and-cold behavior made me think he didn’t really like me, so I sought reassurance. He offered some reassurance but without much conviction. The last day I saw him I’d driven three hours to be with him; I hadn’t been invited — I’d invited myself — and he didn’t encourage me to come. During the visit he wasn’t affectionate, didn’t kiss me or sit close, and although friendly and including me in activities, I felt like a puppy following him all day. My anxiety spiraled; I thought I’d made a mistake coming. I failed to use the tools I know — meditation, walking — to calm myself. I asked him directly whether he still wanted to spend time with me because he felt like a friend, and that question made him uncomfortable. He didn’t answer directly, saying he was “just being himself” and didn’t want bad vibes. Our interactions grew awkward; I should have stepped back until my anxiety settled, but I needed confirmation that he didn’t like me. That night, at dinner, I asked if he would spend time alone with me instead of partying with his friends. He became very uncomfortable and effectively shut down. I became upset that he couldn’t answer a simple question and we argued. I begged him to keep seeing me — pathetic, I know — and finally left. Two days later I texted an apology, which he accepted. We haven’t spoken since the argument ten days ago, and I’ve been in a deep depression. I’m ashamed of how I behaved; he didn’t treat me cruelly and, for only a month, he showed reasonable interest — texting every few days, liking my posts, remembering small things. My past relationships included narcissistic love-bombing, so I crave intense early validation even when I know it’s unhealthy. I ignored signs that he did like me and wanted to include me with friends. His “crime” was not showing enough affection or excitement to meet my unrealistic expectations. I think he might be avoidant and holding back for his own safety. I ruined any attraction he might have felt by acting unhinged, but I also wonder if he was just breadcrumbing me for ego or sex. How do I release the shame and regret? I keep replaying “what ifs”: what if I’d calmed myself, gone along with his party and tried to enjoy it, or not gone that weekend at all? I tell myself that if he were meant for me he’d have given clear, consistent signals and been open to talking, but is that reasonable after only a month? I’ve been in so many toxic situations I don’t know what healthy looks like. Any guidance would be appreciated. Nora, this shows a deep attachment wound that warps thinking at pivotal moments. First, forgive yourself entirely for how this unfolded. The idea that you “ruined a good thing” misunderstands the dynamic: this relationship as it was set up — casual — was never likely to meet your needs. You are not ready for that kind of arrangement, and expecting a casual setup to soothe deep abandonment fears was always a mismatch. He explicitly said he wanted casual; even if you wanted companionship at any cost, that arrangement couldn’t genuinely supply the sustained care you need. People with your history often try to adapt to what’s offered, shutting down needs to fit another’s terms. But you deserve relationships that match who you are and what you can tolerate. Practical points: delay sex with new people. Sexual intimacy accelerates bonding and makes attachment form quickly; it can trick you into becoming attached before you know whether the person will meet your emotional needs. Long weekends and extended early dates magnify this risk — keep initial meetings short and low-pressure so you can observe the person’s behavior over time. In this case he told you he wanted casual — responsible on his part — and you agreed, but your body and heart reacted differently. That internal conflict is what led to anxiety and the behaviors you’re ashamed of. Also, turning up uninvited after a three-hour drive was a boundary violation; showing up without explicit invitation can frighten someone and make them uncomfortable. Even so, he tried to be polite and manage the situation. Regulation tools — breathing, walking, meditation — aren’t meant to anesthetize your authentic self so you can fit someone else’s terms; they help you be present and act from clarity. Using regulation should allow you to honor your feelings and boundaries, not suppress them to avoid conflict. Having trusted friends and communities that provide companionship when you need comfort prevents chasing attachment in romantic partners. Twelve-step and recovery communities provide that steady social access — meetings, people to call, and practice in honesty and accountability. They can save you from seeking quick fixes in relationships and allow you to take the time to heal and wait for healthier connections. You did apologize, and he accepted it. That’s closure on the interpersonal level; now the important work is for you to care for your own wounds. Don’t contact him further; repeated attempts to reconnect will slow your healing. Your shame and craving for intensity are not moral failures — they are understandable reactions to childhood neglect. Treat them as wounds to be tended with support, tools, and limits. Learn to move slowly — get to know someone in conversation and real-life interactions before escalating physically or emotionally. Surround yourself with friends who understand trauma and recovery, and practice self-care when fears arise. You mentioned avoidant tendencies in him; after one weekend it’s not helpful to diagnose. The clearer fact is you were not compatible with a casual arrangement. You didn’t “ruin” things; you acted from a frightened place that needed more safety than that situation could provide. Let him go and focus on building skills, friendships, and supports that let you approach future relationships from a steadier place. Consider recovery groups, therapy, or structured programs that teach emotional tools and provide community. There are options like my membership program, which includes courses, a private group, and regular practice calls; there are also free resources and daily practice tools to help reframe fearful or resentful thinking. Face-to-face friendships matter. If you lack friends now, look into groups like Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous, Adult Children of Alcoholics (ACA), Al-Anon, and similar 12-step communities — places where people are earnest about working on themselves and offering nonjudgmental support. Insecure attachment from childhood often makes people rush into intensity, misread signals, or assume commitment where none exists. Being clear about what you want, communicating it, moving slowly, having tools for regulation, and building a circle of supportive friends are the essentials for change. Finally, my next letter is from Clara. She writes: Hi Crappy Childhood Fairy, I’m 22 and since age 11 I’ve struggled with love and self-worth. My parents separated when I was six. My mother was emotionally unavailable and my father was largely absent but somewhat present early on; when I tried to spend time with him after long workdays he was tired, threatened to hit me to make me go to bed, and sometimes did. Later he formed another family and committed to them. When I was ten, my mom got a boyfriend and traveled a lot; I felt lonely despite living with many family members. I was often treated like a punching bag by my grandfather, who once was affectionate but grew critical and dismissive. My aunt was mean, accusing me of preventing my mother’s happiness when I cried at her leaving, labeling me manipulative. I played rough with my older brother but sometimes his hits hurt more than they were playful, and I’d be blamed because of my high-pitched voice and made to feel like the problem. I admired my brother despite this. Around eleven I entered my first relationship at school with a partner seven years older; it became textbook manipulation and abuse that lasted three years. I’m sorry — that’s severe. After that, I turned to drugs and alcohol and had no friends; when I ended the relationship and told my mother, she said I’d broken her trust and would have to earn it back, blaming a child for abuse and neglect. Eventually I rebuilt something of a relationship with her, but the damage stayed. Since then, my love life has been a series of limerence and short situationships, none lasting over two months. Six months ago I met a man who shared melancholic interests and music from my adolescence. Two months ago we began seeing each other; he told me he’d ended an eight-year relationship two years prior and it had ended badly. We spent time together; he stayed over, we slept together, we visited theaters, parks, had picnics, and sometimes he’d sleep in my bed while I worked. Once he canceled at the last minute; after a week of silence, I reached out and things resumed. But I felt growing doubts and cried a lot wondering if he’d lost interest. One morning he asked whether I preferred monogamy or polygamy; I said monogamy, and he kissed me and said he felt the same. Later I asked if he planned to meet other people and he said “not for now,” which made me uneasy. I asked if he’d tell me if he met someone else and he said he would. A while later I asked whether we were kind of friends-with-benefits; he replied, “You could say that.” I asked if he didn’t want a relationship and he said he had pictured a relationship after his last one, felt safe with me because I’m kind, but feared commitment and couldn’t force feelings or guarantee the future. He also said he didn’t see himself as the person who could help me emotionally. I felt hurt because I wasn’t asking for promises, just wanting to know whether he was willing to stay and work toward a coupledom, which he couldn’t say. When he told me he might be afraid of commitment but felt safe with me, I felt confused. We had agreed to a sexual relationship, which is sometimes okay, but I found myself distressed by the uncertainty and the possibility he wasn’t fully present. We didn’t speak for a week, then he texted asking if he could return some shirts and meet. I prepared for him to break things off, but he said he wanted to keep seeing me. I told him I thought that might not be a good idea because I’d noticed being selfish last time. I think I was punishing myself and trying to control a narrative. Every time I attempted to talk about my fears, he shut down and went silent. He asked why I thought he might leave and I said nothing other than “I feel it,” which wasn’t much of an explanation. Clara, your history shows deep wounds and early abusive experiences that have shaped a pattern of insecurity: rushing into intense attachment, fearing abandonment, and then interpreting ambiguity as imminent loss. Dating for two months, it’s reasonable for someone not to commit; wanting to know whether a partner is likely to stay is natural, but being clear and steady in how you communicate is crucial. You seem to oscillate between saying you don’t want commitment while emotionally craving it, which creates confusing signals. If you say “we’re friends with benefits” as a way to protect yourself, but underneath you want more, that contradiction often provokes anxiety and pushes the other person away. Sexual intimacy can accelerate bonding in a way that makes uncertainty feel intolerable. That’s why the advice to go slower exists — delay sex until you have more consistent evidence of someone’s intentions. Two months is early for hard guarantees; many people simply aren’t ready to promise a future that soon, and it’s healthy for them to be cautious. However, your pattern of reading potential abandonment into small steps and then acting from fear (which can come across as manipulative or controlling even if that’s not your intent) sabotages your chances. When your partner says he’s afraid of commitment and can’t promise your future, that’s significant information. You can accept the relationship’s current terms and protect yourself emotionally — keep boundaries, manage expectations, and decide if this arrangement aligns with your needs — or step away to avoid ongoing hurt. The core tasks for you are similar to those already mentioned: go slowly, develop tools for regulating fear and shame, cultivate supportive friends and groups who model healthy attachment, and learn to express needs clearly without coercion or punishment. Therapy, recovery groups, and communities where people are working on themselves can teach new relational skills and provide steady companionship so you’re less dependent on a single partner for emotional survival. In all three letters, the common threads are attachment wounds from childhood neglect or abuse, the tendency to rush into intensity, the challenge of confusing casual arrangements with genuine care, and the same remedies: slow pace, boundaries, self-regulation tools, honest communication, supportive peers or groups, and programs or therapies that teach how to manage shame, anxiety, and relationship behaviors. Healing is possible. With steady practice, appropriate social supports, and clearer self-knowledge, people can outgrow destructive patterns, find friends and partners who match their level of growth, and build relationships where they truly feel cared for.

That isn’t fair — you were afraid he might leave you, and given statistics that’s a reasonable fear. But I don’t think his behavior came from an intention to abandon you. You say he never contradicted your assumption, so you kept pushing him, essentially testing him by saying things like “you don’t even care about me,” waiting for him to protest and say “yes, I do.” Instead he seemed put off, hurt, and confused by being pressed in that way. You told him that if you stayed out of fear you’d only grow more attached while he stayed the same; in response he, a bit annoyed, said he wouldn’t force you and he wouldn’t force himself. You told him you didn’t want to force him either, and you separated. What I hear is that you were demanding a declaration that he wanted to be with you and putting him on the spot. If you continued the relationship you would sink deeper into attachment while he likely wouldn’t catch up emotionally — he wasn’t promising that he would fall in love with you; he was simply dating you in the present.

Carla, I want to help you see the distinction between dating and being in a committed relationship. You were in the dating phase, yet your heart was already seeking a relationship. If you grew up with neglectful or unreliable caregivers, how could you learn to tell the difference? Now you’re here, getting guidance. Dating and relationship feelings can get mixed up, especially when sex is involved: mind, heart, and body can create a sense of being “in” something even when the other person hasn’t made that commitment. This pattern — bonding quickly through sexual intimacy — is common, especially among women and people with childhood trauma. It’s why moving more slowly can prevent that rush of attachment that later leaves you wondering what the relationship even was. From what you described, you pushed for a proof of devotion and then felt ashamed and hid your feelings when things didn’t go as you hoped.

You said he never told you “I want to be with you” or that he could imagine a future with you without caveats, and he didn’t say he would keep trying in a way that recognized both your wounds and his. Maybe he’s uncomfortable with emotional conversations and a bit avoidant; I want to allow for that possibility. But you were also harsh and a little manipulative in trying to provoke a declaration by speaking from fear. That kind of test — “you don’t love me, are you sure?” — puts an enormous and unfair demand on someone after only two months of dating. Partners don’t have to fully explain every reason you feel a certain way; they should listen, respect boundaries, and be honest, but it’s unrealistic to expect them to understand all the roots of your feelings like a parent might. Use the dating period to observe who they are and how they behave: do they follow through, do they call as promised, how do you feel when you’re waiting for contact or when you’re with them? Those are the clues that tell you whether it’s worth taking a next step.

You told me he said he couldn’t force himself to feel more after two months, which is understandable. Yet you can’t seem to be satisfied with leaving it at that — you miss him and can’t shake the knowledge that he wanted to keep seeing you and showed care and affection. Some people in your position have had partners say plainly “I don’t want a relationship” and still can’t stop thinking about them. In your case, this guy kept showing interest but wasn’t fully committed, so there may be unresolved things between you. You may have left too soon, not because you shouldn’t have spoken up, but because the situation could perhaps be salvaged with work on your side. You need ongoing help — therapy, a structured program, or a support group — to process emotions and get a reality check so you don’t approach new situations from immediate alarm and fear of abandonment.

Abandonment wounds are painful and act up even when people are treating us kindly. The better path is to heal over time so that early dating stages aren’t dominated by pleas and accusations like “you’re abandoning me” or “you’re mistreating me” whenever fear flares up. If this man was as kind as you describe, it’s possible to reconnect thoughtfully: apologize for jumping the gun, explain that you liked him and wanted it to work but that fear made you push, and say you’ve started getting help to manage these reactions. Another clinical term for your pattern is disorganized attachment: you feel intensely for someone, yet when they’re present you push them away. That style is very painful and requires consistent, steady work to learn to stay centered — not rushing in nor precipitously pulling back.

Before the breakup, his affection felt genuine, which makes the loss sting more. You wonder if, without your insecurities and a difficult relationship history, you might have been able to tolerate going out without demands for labels. At two months, it’s normal he wasn’t ready to call it a relationship. You’ve said it’s the first time you ended a “situationship” without completely emptying yourself out — usually you stay until you’re depleted. Here, both of you wanted to continue but on different terms, and perhaps it’s kinder that things ended now than festering into resentment — but grief is real, especially when you’ve been trying to improve and cultivate self-sufficiency in the aftermath of past hurts. You feel you lost someone because of your insecurities, and that’s heartbreaking.

You wanted acknowledgment that what you shared was a relationship and maybe some hope that he’d want to build on it; those desires are valid. At the same time, you held back at times to avoid making him uncomfortable, yet you also expressed things that likely made him uneasy. You worry you’ll always be “too much,” always feel more than the other person. This time you tried to protect yourself by stepping back, but you keep wondering if that was the wrong move.

Here’s a practical suggestion: if you like this person and he’s not involved with somebody else, consider apologizing and asking to reset — date without sex for a set period so you can pace how close you get. For someone with your attachment wounds, having sex early accelerates bonding and can make it very hard to regulate feelings. A reasonable window is three to six months of dating without sex, allowing both people to see how feelings develop naturally. When you do talk about your feelings, be honest but measured; complex and intense displays can overwhelm someone who isn’t used to them. With CPTSD, pain from the past leaks into the present and can seem bewildering to others, which is why they might respond with confusion. Healing will reduce how often you appear “too much.” A chaotic or neglectful upbringing can deprive a child of a sense of identity — not only who they are but what they like or want. That emptiness can lead a person to seek validation through relationships or through the very idea of being in a relationship, to feel rooted and real.

The next section is from a letter I’ll call “B.” She writes that she grew up with a mother who had untreated borderline personality disorder and depression, a brother with severe Tourette’s and learning and anger issues, and a father who worked long-haul trucking and was often absent. It was essentially a single-parent household where fights were constant and sometimes violent. Her mother loved her but became enmeshed and made her the “golden child,” while the brother’s needs and the mother’s illness left her feeling neglected. She was forced to forgive and love her brother no matter what and punished harshly for small missteps because she was the “well-behaved” one. The result was a people-pleasing, anxiously attached person who tended to idolize others, excuse their flaws, and struggle with identity.

At twenty she moved to another country for a man she met online. Almost five years there, then the relationship fell apart and she had to return to Canada with only 28 days’ notice, a shock that left her world in ruins. Back home, her mother had sunk into deep depression, her father had lost his job, and the house was cluttered with hoarding. She blamed herself for leaving, feeling responsible for their decline, which isn’t accurate; pursuing a life outside a dysfunctional home was reasonable. Overwhelmed, she started escaping by traveling with unhealthy companions who enabled the trips — and with that tolerance came abuse. On one trip she met a man from Texas, fell hard, and believed he’d offer a new life. He told her upfront that he was damaged, had a history of addiction and suicidal thinking, and didn’t want a relationship. She heard that as frankness and thought he was self-aware rather than recognizing the red flags.

Within weeks they were seeing each other; she flew to Texas frequently and they spoke daily. Six months in they planned a multi-city U.S. trip, but on the second day he publicly broke up with her. Instead of leaving the trip she essentially erased the breakup and they continued the holiday, staying intimate and affectionate even though she knew the relationship had been ended — a classic dissociative response. This illustrates how trauma and a lack of emotional training from childhood can leave someone unsure what to do in such a crisis. The right move after a breakup would have been to separate, but she didn’t know that then.

Two months after returning to Canada the pandemic began and he reappeared; they became quarantine companions, spending hours on the phone and watching movies together. He stayed “broken up” but continued flirty, affectionate behavior, and she interpreted this as possible hope, even though he repeatedly said he didn’t know if there was a future for them. Her tendency to hold on to the best possible outcome is rooted in childhood: she learned to adapt, be agreeable, and hope for repair. That pattern of accommodating inconsistent people only makes it easier for someone to come and go without committing. If you’re drawn to emotionally unavailable people, write a list of non-negotiable qualities and include a partner who is genuinely excited to be with you; date people who match that standard. Continuing to sleep over and act as if everything is normal after a breakup often signals to the other person that you accept their indifference and won’t require commitment.

That particular man eventually pulled away more and more. Each time he stretched distance she grew more desperate to draw him back — echoing the trauma-driven reaction of clinging when someone withdraws. Conversations became focused on his depression, turning into therapy-like exchanges, but she isn’t his therapist. This dynamic — trying to extract love from someone who’s struggling with severe mental health issues and perhaps substance problems — is damaging for both parties. Each visit would bring a temporary re-ignition of warmth and attention, followed by another fade, resembling the cycle of intermittent reinforcement that creates obsession: occasional reward, then withdrawal, then reward again. It’s a potent way to get stuck chasing a relationship.

She feared that if she fully withdrew he might harm himself; he had said he had no one and had mentioned suicidal ideation. That creates enormous pressure and a sense of responsibility, but she is not his clinician. When people are in immediate danger, the right step is to urge them to call hotlines, contact therapists, or access emergency help — not to assume you can keep them safe by staying in a harmful pattern. You can encourage someone to get professional support, then step back. The principle from 12-step recovery applies: you didn’t cause this, you can’t control it, and you can’t fix it. Protecting your own well-being is essential; staying in that dynamic prevents you from having healthy friendships and relationships.

Given all of this, she was advised to stop contact with that man. His problems — suicidal ideation, addiction history, unpredictability — make him inappropriate for a dating relationship. If he has such severe instability, he needs professional help, not the emotional labor of a romantic partner. She was urged to seek support herself through meetings and recovery communities that can offer understanding and structure: Al-Anon or Families Anonymous, Adult Children of Alcoholics/Dysfunctional Families (ACA), Co-Dependents Anonymous (CoDA), and other 12-step or mutual-support groups. Those spaces provide people who understand these dynamics, can offer guidance, and help build real friendships and accountability. There are also therapeutic courses, memberships, and programs that offer tools and a supportive community.

This situation isn’t your fault — your childhood injuries shaped how you handle attachment — but there is a path forward. With the right resources, steady work, and connections to people who get it, you can heal and stop getting pulled into relationships that leave you stranded and hurting. There’s hope in getting the right help and learning new ways to date, to set boundaries, and to protect your heart while you let someone show you who they are over time.

Çocuklukta İhmal ve Kendine Zarar Verme (4 Videoluk Derleme)">

Çocuklukta İhmal ve Kendine Zarar Verme (4 Videoluk Derleme)">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

THIS PROVES an AVOIDANT Wants You FOREVER (and Loves You Deeply)">

THIS PROVES an AVOIDANT Wants You FOREVER (and Loves You Deeply)">

Why Your Traumatized Self CRAVES ORDER">

Why Your Traumatized Self CRAVES ORDER">

The 5 Unspoken Rules for Making an Avoidant Man Finally Crave a Deep Connection">

The 5 Unspoken Rules for Making an Avoidant Man Finally Crave a Deep Connection">

">

">

I figured out why my Relationships kept Failing.">

I figured out why my Relationships kept Failing.">

Sınırlar Narsistlerde İşe Yarıyor mu?">

Sınırlar Narsistlerde İşe Yarıyor mu?">

Travmanın Etkilerinden Daha Hızlı İyileşmek İçin İpuçları (4 Parçalık Derleme)">

Travmanın Etkilerinden Daha Hızlı İyileşmek İçin İpuçları (4 Parçalık Derleme)">

Pornografi, ilişkiniz için SON DERECE tehlikelidir">

Pornografi, ilişkiniz için SON DERECE tehlikelidir">

Bu TEK Sevgi Hilesi, Kaçıranlarla Kırılmaz Bağlar Yaratır">

Bu TEK Sevgi Hilesi, Kaçıranlarla Kırılmaz Bağlar Yaratır">