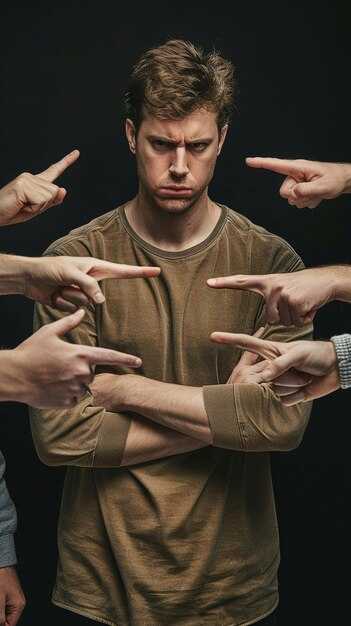

People often ask me which of my videos about trauma I consider most impactful, and there’s one I want to bring to your attention now. It focuses on the signs you may notice in yourself today that reveal you were neglected or excluded as a child. When I first shared it, viewers found it deeply affecting. If you wrestle with feeling left out, this is for you. No one enjoys being ignored, excluded, or abandoned, and many adults with childhood PTSD carry those wounds from early experiences. Maybe your caregivers were addicted and emotionally absent, flipping off their attention the moment you needed support. Perhaps a parent died, was imprisoned, or walked away as if you never existed. Those things are devastating for any child, and they can seriously complicate adult relationships—unresolved anxieties and unmet longings can make stable, close bonds feel impossible, whether romantic or otherwise.

Abandonment wounds often push people into relationships too quickly because the nervous system never learned “slow.” It’s something you can retrain with specific strategies, which I teach, but as a child you didn’t have the tools for that patient pace. So you may attach to someone intolerable or hurtful and feel unable to leave when the old abandonment alarm goes off. The idea of leaving can feel unbearable, as if it would be worse than dying, and that’s how people get trapped. These wounds can also surface in group settings—I’d bet you’ve felt excluded, shunned, or judged by peer groups. I’ll cover that here too.

I’ll explain why these wounds are easy to miss in yourself. When your abandonment alarm is triggered and you “flip out” on someone, you often feel like you’re not yourself. The desperate, sometimes intense reaction to the sense of being abandoned—often when no one has actually left you in that moment—feels like a nightmare replaying. That’s an emotional flashback, a core feature of complex PTSD: an emotional state from the past returns and overlays the present. For example, someone leaves the room while you’re talking and a tidal wave of panic and grief washes over you. That’s an abandonment wound activating, and then you might lash out, call names, threaten to walk away, or collapse into tears, feeling like everything has ended. Pete Walker coined the term “abandonment mange” to describe the intense mix of grief, rage, and panic that floods people when abandonment is triggered—an emotional flashback that pulls in the child experience.

I want to explore why this happens and how injuries suffered before you had language can show up later as raw emotions that seem dissociated from current reality. You may not recall a concrete memory, but the feelings arrive as if they’re happening now. Let’s run through common triggers linked to childhood abandonment. The useful thing about identifying triggers is that CPTSD symptoms only appear when they’re triggered. That includes neurological dysregulation, emotional disconnection, and self-sabotaging behaviors—lashing out, running away, substance use—many maladaptive habits quiet down and stay dormant when you aren’t being triggered. You can’t prevent the world from presenting triggers, but you can learn to modulate your responses once you recognize them and have tools to calm yourself. Here are triggers that often set off abandonment wounds.

One common trigger is someone leaving the room mid-conversation. Some people—those with or without CPTSD—manage intense talks by creating physical distance, stepping out briefly to self-regulate. That’s different from permanently leaving the relationship, though it can stem from the same flight impulse. For someone with CPTSD, a person stepping away, even briefly, can reawaken an ancient ache—memories from before age three aren’t semantic but emotional: you may not recall events, only the feeling of being alone, of crying in a wet diaper. The feeling comes back as if it’s happening now, and without a clear cognitive memory to contextualize it, you assume the current person is terrible and decide to shut down the connection. Later, when you partially calm or dissociate, you might notice and regret what you did—many people with this history have, at times, damaged relationships and then wondered, “What have I done?”

A related trigger is the silent treatment. That ranges from a partner refusing to discuss something to a whole peer group turning their backs and shunning you. Stonewalling (“I won’t talk about it”) and the more punitive silent treatment can be profoundly destabilizing for someone who was rejected or ignored as a child. While you can’t control others’ behavior, understand that withholding communication in this way is emotionally immature and can be abusive; it’s not something you should tolerate long-term without boundaries or change.

Waiting is another major trigger. If you grew up left at daycare, waiting by the window for a parent who never showed up, that pattern of unmet needs around waiting becomes wired into your system. As an adult, any sort of waiting—an unreturned call, a partner who doesn’t show—can stir panic and fog. Your mind may try to minimize it (“It’s probably just me”) and you’ll question whether your feelings are valid. In communities I run people frequently ask, “Is it just me?” when a partner flakes, and the supportive answer is often, “No, that was disrespectful.” You are allowed to set boundaries around punctuality and reliability; if you don’t, you’ll keep drawing people who don’t take you seriously.

Jealousy and the experience of being gaslit about it are powerful triggers, especially in dating. Someone may break up with you and say, “Let’s stay friends,” and later you watch them move on while you have to pretend not to be hurt. Being expected to behave as if something that hurts you doesn’t matter can push you toward dissociation. Narcissistic or manipulative behavior online—trolling, canceling, lying about you—can also force you into your CPTSD, shutting down your ability to defend yourself. If your parents were neglectful—addicted, selfish, emotionally unavailable—you were likely dismissed for being sensitive (“Get over it,” “You’re too much”), and that shame sticks until you learn to regulate those triggers. You don’t have to accept arrangements that violate your boundaries; jealousy often reflects a reasonable expectation of loyalty and you’re allowed to enforce what feels important to you without shaming yourself.

Empty time—hours with nothing planned—can be a trigger too. If your childhood included long stretches where needs were ignored, being alone can elicit anxiety. Some people fill every hour with activity to avoid feeling abandoned. The upside is that healing work teaches you to use solitude productively: sitting with uncomfortable feelings, writing them out the way I teach, and discovering what arises when you’re not constantly distracted can be fertile ground for recovery. Some of the deepest healing has happened on dark, lonely nights when I wrote through my fears. So empty time can be reframed into a healing opportunity.

Ironically, closeness from loved ones can also trigger you. I remember my father when he was dying; a few months before he passed from ALS I visited him. He stood in the driveway, smiling and waving goodbye with so much sorrow and love that I wanted to run into his arms—but the intensity felt like a firehose, and I couldn’t take it in. Losing my dad while I was young was another form of abandonment, even though it wasn’t intentional. That loss, following my parents’ divorce and our move away, shaped how I related to people later. He wrote me letters that encapsulated his love, knowing he probably wouldn’t live to see me grown; those letters have been a deep source of comfort, though even holding them is overwhelming sometimes. Intense demonstrations of love can reopen wounds when you never had the chance to integrate steady care as a child.

Seeing others navigate social situations with ease—“why didn’t I get the memo?”—can be painful. You may compare yourself and assume others are effortlessly accepted, which triggers preemptive withdrawal. Sometimes other people genuinely do fit in easily; other times you’re overlaying past wounds onto the present. If you often feel you don’t belong, you might also find yourself in groups where you actually don’t fit, because you sought companionship at any cost. Learning to articulate your needs and make modest requests—asking to join, inviting yourself into plans—takes courage, but it’s a practice that helps you test whether you’re included or merely imagining rejection.

Ostracism, feeling overlooked, judged, condescended to—these all tie back to the fear of not being enough. In school you may have learned to keep your hand down to avoid humiliation when someone else got called on. Later in life this translates into staying silent or minimizing yourself to avoid being overlooked. Feeling judged often signals an internal component: if others’ opinions hurt you deeply, there’s likely some self-criticism to work on. Sometimes the problem is simply mismatch: you don’t fit with a particular group and that’s fine. Other times your trauma-driven reactions can push people away, creating a self-fulfilling cycle. Healing involves doing your inner work and also practicing the kind of outward openness that invites healthy relationships.

Another common, nearly universal trigger for people with childhood PTSD is hurrying. We all rush through life, but for those with early trauma, hurrying easily escalates into overwhelm and dysregulation. Our culture normalizes rushing, but when you hurry while caring for children or working, it can sabotage everything. Underneath much of our hurry is procrastination fueled by dysregulation: avoid, then scramble, then get triggered, rinse and repeat. Slowing down—taking time to savor a shower, brush your teeth without racing—can be profoundly re-regulating. When I slowed my activities and allowed emotions to arrive instead of constantly running from them, the sense of being chased diminished. Instead of a frantic pack of wolves at my heels, the feelings came, I let them flow, and they passed.

Neurological dysregulation is the core issue for adults who experienced childhood trauma: brain rhythms fall out of sync when triggered, causing scattered thinking, racing heart, and emotional surges. If you can identify dysregulation and re-regulate quickly, you change the course of many trauma symptoms. That’s why I focus on re-regulation techniques: writing tools and simple meditations that help you return to baseline. Slowing down, using lists and structure, and building rituals for focus are practical ways to reduce urgency. For instance, I use a Kanban-style app to manage tasks, which keeps my day orderly and prevents last-minute scrambling. Going slower paradoxically often makes you more efficient.

There are practical rules I follow now to protect myself when I’m prone to dysregulation: no driving while dysregulated—when you’re out of sync mentally it’s as dangerous as drunk driving—and a morning routine that includes writing out fears and resentments before taking on difficult conversations or tasks. I’ve learned the hard way: at a moment of intense dysregulation I drove off with a gas pump still attached; I’ve even rear-ended a truck. When your brain waves are scattered, sequential tasks fall apart—putting a card into a pump, pumping gas, closing the cap becomes impossible. Understanding that helped me create boundaries and habits that keep me safer.

Because dysregulation steals attention and productivity, tasks like getting interrupted repeatedly, being silenced, or not being validated can spiral you into an overwhelming state. I get deeply dysregulated by frequent interruptions; when that happens I rely on writing to capture what I wanted to say, so I can return to it later without losing my composure. Keeping paper by my bedside helps when anxious thoughts wake me; I jot them down and return to sleep rather than letting them loop.

Shopping in busy, noisy stores, especially for big purchases, is another trigger for me—sights, smells, and chaos make me dizzy and impulsive. Online shopping and services that bring goods to you—like test-driving a car at home—work better because they reduce sensory overload. Large, crowded events like street fairs or loud music remind me of chaotic childhood environments. Certain sounds and odors (some health-food stores’ aromas) bring up negative associations from a commune I lived in as a child, where some experiences around nudity, substance use, and strange rituals left me feeling unsafe. Those sensory cues can instantly drag me into old, painful states.

Public aggression and yelling are deeply upsetting to me because, growing up, loud anger often led to violence. I remember an intense incident at a parking lot where a woman started honking and shouting, then physically assaulted my husband with a stroller—an act that pushed me into hypervigilance. When people are verbally cruel online, it can also send me spinning. Although it’s tempting to fire back, responding to trolls rarely helps; I usually remove abusive comments and protect the space instead.

There are many other personal triggers I still notice: being woken repeatedly, fearing someone is angry behind my back (and the instant jolt of seeing a hostile comment online), long, complex conversations before I’ve done my grounding practice, food that spikes my blood sugar (flour and sugar early in the day worsen dysregulation), and the sense of being unprepared or exposed in a professional setting. For example, a technical failure during a paid webinar made me feel responsible and out of control, which dysregulated me despite my experience leading hundreds of Zoom meetings. Receiving conflicting medical advice from well-meaning people can also be destabilizing when I’m trying to heal; unsolicited direct advice is a trigger for me. Opinion bullies—people who insist they’re right and attack anyone who disagrees—are exhausting and hurtful. Those dynamics, in person or online, can push me away or shut me down.

All of this is to say: the world will keep offering triggers, but your trauma-driven reactions are what you can change. Instead of shutting down, withdrawing, or lashing out as your only defense, you can practice noticing when you’re being triggered and use tools to calm down. That creates a small gap between stimulus and response where you get to choose. I learned to do this through a daily practice of writing and brief meditation; it has transformed my life and is the core of what I share with others. Hundreds of thousands of people have used these techniques. If you haven’t tried them, consider giving them a shot.

Isolation is an almost universal outcome for people who grew up with trauma: either you feel isolated among others or you literally cut them out. Pulling away can feel like the most self-protective, sensible act when you’re dysregulated—it gives you room to breathe and prevents you from having your nervous system triggered. But using isolation as a long-term strategy locks you out of most opportunities for belonging. Some people genuinely prefer solitude or need a period of withdrawal for recovery; that’s valid for a time. But if isolation becomes your habitual solution, it narrows your life and closes doors to connection, care, and practical support. People need community: other humans grow food, build infrastructure, visit you in the hospital, drive you home when you’re discharged. Your immune system, mental health, and resilience benefit from supportive relationships. Remaining socially isolated can create a developmental barrier; human interaction, even small kinds of helpful contact, is necessary for ongoing growth.

Avoidance often starts as covert strategies—staying “functionally” engaged while keeping relationships superficial. You cancel plans, make excuses, or appear present but aren’t truly available. That may protect you from immediate dysregulation, but over time it shuts down a life of meaningful contribution and reciprocity. If you’re using isolation as a long-term fix, notice whether it’s driven by trauma. Sometimes people can sustain it, but many can’t: financial needs, illness, aging—life eventually requires help and connection. Healing the urge to withdraw is crucial because it restores access to the very things that sustain us. You can begin with small steps: learning to spot the triggers, practicing self-soothing, setting reasonable boundaries, and gently increasing the amount of authentic presence you tolerate.

There are several reasons isolation feels compelling: social situations are full of triggers; avoiding them reduces short-term distress. But if you habitually withdraw, every opportunity to belong becomes rarer and harder to rebuild. People who champion isolation as a badge of honor are often masking grief or fear. Solitude is a different, healthy choice; isolation as a trauma response spreads stagnation. It’s better, when you can, to face discomfort in relationships, feel the sorrow for the connections lost to trauma, and gradually repair your capacity to be with others.

When you begin to reduce the power of your triggers, isolation loses its appeal. You’ll find it possible to choose connection more often. Remember: many people who were neglected or abused as children develop these patterns—it’s not your fault. Now that you’re an adult, you can learn to spot hurtful people and protect yourself while also learning who to trust. Go slowly, be curious, and practice the skills that let you be yourself in relationship. We’re all works in progress.

To sum up some practical steps: pay attention to how hurrying affects you, practice slowing your pace, use lists and structure to reduce last-minute rushes, create a morning ritual (writing and short meditation) that grounds you before heavy conversations, learn to notice dysregulation and re-regulate quickly, and experiment with gentle exposure to social situations so your capacity expands over time. Slowing down, writing your fears and resentments on paper, and meditating are foundational tools for creating a stable baseline. When you’re better regulated, other parts of life become accessible again—work, parenting, friendships, creative expression—and the cycle of avoidance and shame loosens.

I had a very dysregulated week recently that illustrates how triggers still show up. Returning from a live show in Los Angeles, on the long drive home we encountered a severe multi-car crash. A vehicle crossed the median, flipped, and blocked the highway; we all got out and helped move debris. There were injured people—one woman being pulled from the wreck, and a man on the ground who could move his toes and was conscious. I sat with him, kept him warm, and spoke to him calmly until the ambulance arrived. That night, I noticed how the event stunned me: violence and real-life injury are major triggers for me. Talking about what happened in the car afterward, my voice was oddly flat and detached—one of the ways dysregulation shows up. Sometimes speaking about trauma can itself be destabilizing, and though friends reached out kindly, the combination of shock, having to recount the event, and not getting immediate comfort from the people with me made me feel strangely checked-out and agitated.

From that incident I reflected on a set of triggers I still carry. Some are the four that activated that night—real-life violence, retelling traumatic events, being silenced or ignored, and interruption—but there are many more I track: being interrupted repeatedly (which fragments my thinking and work), chaotic shopping environments, feeling left out, feeling unprepared or embarrassed in professional settings, public ridicule, opinion bullies, loud crowds or street fairs, smells and sounds that evoke early traumatic settings, public nudity tied to a past lack of safety, screaming or threats that recall past violence, sugar-heavy breakfasts that throw me off my baseline, repeated awakenings during the night, the fear someone is secretly angry or talking behind my back, and heavy, complex conversations before I’ve done my grounding routine.

I’ve learned strategies that help me manage these triggers. Writing—especially the technique I call the daily practice, where I name my fears and resentments—is a central tool, paired with a brief meditation. These practices are taught in free courses and resources I’ve made available, and they are the core routine I use to re-regulate and thus be able to show up more fully in life. The goal is not to eliminate all triggers (you can’t stop the world) but to change how you respond so you don’t have to keep withdrawing from life. Little by little, when you practice noticing and calming your nervous system, you can reclaim belonging, deepen relationships, and reduce the influence of those old childhood wounds. There’s no rush—take it step by step, keep practicing, and the capacity to connect will grow.

Ο Πραγματικός Λόγος για τον Οποίων Εμφανίζονται Ξανά τα Συμπτώματα του Τραύματός σας (Συλλογή 4 Βίντεο)">

Ο Πραγματικός Λόγος για τον Οποίων Εμφανίζονται Ξανά τα Συμπτώματα του Τραύματός σας (Συλλογή 4 Βίντεο)">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

ΑΥΤΟ ΑΠΟΔΕΙΞΕΙ ότι ένας ΑΠΟΦΕΥΚΤΙΚΟΣ Θέλει ΕΣΑΣ για ΠΑΝΤΑ (και σας ΑΓΑΠΑ βαθιά)">

ΑΥΤΟ ΑΠΟΔΕΙΞΕΙ ότι ένας ΑΠΟΦΕΥΚΤΙΚΟΣ Θέλει ΕΣΑΣ για ΠΑΝΤΑ (και σας ΑΓΑΠΑ βαθιά)">

Γιατί το τραυματισμένο σου ΕΑΥΤΟ λαχταρά ΤΑΞΗ">

Γιατί το τραυματισμένο σου ΕΑΥΤΟ λαχταρά ΤΑΞΗ">

Οι 5 Ανείπωτοι Κανόνες για να Κάνετε έναν Αποφεύκων Άνδρας να Επιθυμεί Τέλος μια Βαθιά Σύνδεση">

Οι 5 Ανείπωτοι Κανόνες για να Κάνετε έναν Αποφεύκων Άνδρας να Επιθυμεί Τέλος μια Βαθιά Σύνδεση">

">

">

I figured out why my Relationships kept Failing.">

I figured out why my Relationships kept Failing.">

Do Boundaries work on Narcissists">

Do Boundaries work on Narcissists">

Tips to Heal FASTER From Effects of Trauma (4-Video Compilation)">

Tips to Heal FASTER From Effects of Trauma (4-Video Compilation)">

Pornography is EXTREMELY dangerous to your Relationship">

Pornography is EXTREMELY dangerous to your Relationship">

This ONE Affection Hack Creates Unbreakable Bonds with Avoidants">

This ONE Affection Hack Creates Unbreakable Bonds with Avoidants">