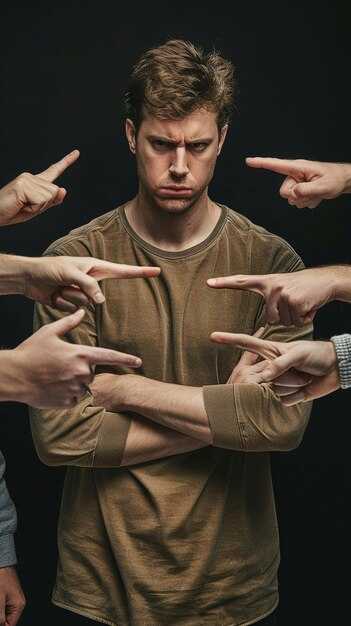

Ever wondered why someone who has ignored you for weeks suddenly floods your phone the moment you stop caring? Why they take days to reply but the instant you distance yourself, they can’t stop thinking about you? This isn’t fate or magic — it’s psychology. Once the mechanics are clear, the feeling of being powerless in relationships, especially with an avoidant partner, begins to fade. There’s a rule that runs through love, work, and human behavior alike: we prize what’s scarce. Scarcity breeds desire; abundance breeds complacency. It’s visible everywhere. Limited-edition sneakers that sell out instantly become coveted. The final slice of pizza at a party becomes everyone’s pick. The same forces are at work in your relationships, whether you admit it or not.

If love with an avoidant has been your experience, this will be familiar. You poured out affection, were always reachable, rearranged your life to stay connected, while they maintained a cool distance and kept control. You might have told yourself, “If I love them harder or prove I’m safe, they’ll open up.” The reality is the opposite: the more available you are, the more their brain concludes, “This is always here; I don’t need to invest now.” Certainty kills the drive to pursue; threats to loss trigger urgency. That surge of urgency is not random — it’s the same reward circuitry that keeps gamblers pulling the lever. Intermittent reward, not constant access, creates craving. That’s why stepping back often produces the unexpected opposite reaction.

What follows is a plain explanation of what happens in an avoidant mind when overgiving stops and emotional scarcity is introduced. A step-by-step psychological map shows how behavior shifts, why chasing starts, and the stages from confusion to panic to pursuit. This is not a manipulation technique to be used like a game — used that way it will fail. The point is reclaiming agency, clarifying needs, and testing whether this person can meet them. Now, let’s examine the wiring of an avoidant mind that leads to ignoring when things are available and obsessing when they are not.

Start with the blueprint. An avoidant partner isn’t merely slow at texting or hesitant to say “I love you.” They operate from a long-established program installed long before the current relationship — a core belief that intimacy is dangerous and distance is safety. Avoidance rarely arrives overnight. It usually grows from childhood patterns: caregivers who were physically present but emotionally distant, messages to “toughen up” instead of being comforted, or early lessons that feelings were burdensome. A child who repeatedly encounters a closed door learns to stop reaching and to rely only on themselves. That survival strategy becomes a default.

In adulthood that strategy still shows up. Avoidant people want connection, but when closeness grows too intense or feels dependent, their nervous system signals danger. They may back away, cancel plans, pick fights, or bury themselves in work or hobbies — anything that restores space. Not because affection is unwanted, but because intimacy triggers a loss of control. When paired with an anxious partner who leans in for reassurance, the dynamic becomes a vicious cycle: the more you move closer, the harder they pull away, and you end up doing most of the emotional labor.

Here’s the crucial point: avoidants are most comfortable when they control the relationship’s power balance. If they can count on unconditional availability, they can keep others at arm’s length while remaining secure that they won’t be abandoned. So the very qualities that feel noble — consistency, loyalty, unconditional care — can unintentionally enable withdrawal. Their brain has cataloged your devotion as a constant, and anything regarded as certain lacks the urgency to be preserved. That’s where emotional scarcity changes the rules: shifting from “always there” to “I have boundaries, needs, and a life of my own” disrupts the system that’s been benefiting from your predictability. Introducing uncertainty alters the game they thought they were winning.

But remember: avoidants aren’t villains trying to cause pain. They are coping with fear — the fear that closeness will subsume them or replicate past hurts. Understanding this default lessens the tendency to take distance personally and reframes it as a longstanding survival setting. Persisting in “loving them out” of avoidance leads to burnout. Creating genuine space and allowing scarcity to do its work can, however, produce change.

Why does scarcity jolt an avoidant attachment system? Because when you have been the constant, the steady presence, the one who always forgives and shows up, their brain places you in a “permanent access” category. Permanent access eliminates urgency. Consider the phone charger example: if it’s always beside the bed, there’s no scramble; but if it’s distant and the battery is low, panic sets in. That scramble is what scarcity triggers in the brain.

Biologically, brains are wired to protect what matters. When a valued resource is threatened, the stress response kicks in — adrenaline, cortisol, dopamine — the same mix that fuels gambling and intermittent reward seeking. When love is treated like an all-you-can-eat buffet, there’s no compulsion to fight for it. Withdraw the buffet and the brain reacts: “Wait — this might be gone.” This isn’t a conscious calculation in most avoidants; it operates at a nervous-system level. Competitive instincts and loss aversion prompt pursuit. If the avoidant has been the less invested partner, your withdrawal flips their advantage: detachment no longer wins when the risk of losing you becomes real.

Many relationships show this: the moment the over-giver stops sending morning texts, stops rescuing moods, or stops rearranging life to accommodate the avoidant, change occurs. Initially, confusion or irritation may surface, but underneath grows anxiety: “Are they really gone? Did I misread things?” Scarcity acts on two fronts. It undermines their sense of control — they no longer dictate the emotional pace — and it forces an admission they’ve long avoided: they care more than they allowed themselves to admit.

A hard truth: scarcity is powerful but not magic. If employed purely as manipulation to make someone chase, any response will likely be short-lived. Long-term change requires sincerity: withdrawal must be rooted in unmet needs and self-respect, not a tactical ploy. When the pullback is authentic, scarcity can flip the script and transform distance into pursuit, silence into reaching out, and control into vulnerability.

Next is a clear breakdown of the six predictable stages an avoidant commonly moves through when scarcity is introduced. Recognizing these phases removes doubt and helps interpret signals accurately.

Stage one — confusion. They notice a shift: fewer texts, less initiation, a cooler tone. Panic hasn’t set in yet; it’s filed under temporary explanations: busy, stressed, distracted. Occasional check-ins may appear, but no major moves. This stage is largely observational.

Stage two — recognition. The pullback persists and becomes unmistakable. Your reduced availability and warmth register. Anxiety begins: “Has something changed?” But they still hold back from major action.

Stage three — light pursuit. Testing begins. Small messages, casual invites, a tentative “what are you up to this weekend?” They’re assessing whether a return to the old dynamic is possible. If the response restores the prior pattern, the cycle resets. If not, escalation follows.

Stage four — panic. Low-effort withdrawal tactics fail. Alarm bells ring and a real sense of losing control rises. This is when they might raise relationship topics, ask direct questions, or increase both the frequency and emotional intensity of contact.

Stage five — desperation. Scarcity fully activates attachment. Larger gestures appear: emotional disclosures, planning meaningful dates, reminiscing, or promises to change. Statements like “I want to work on this” or “I miss us” come from anxiety overriding avoidance. Crisis motivation can be powerful, but it’s not equivalent to lasting commitment.

Stage six — breakthrough or shutdown. Either the walls come down and genuine vulnerability follows, leading to sustained investment, or the fear of intimacy overwhelms and they retreat completely. This latter outcome is less common when scarcity is sincere, but it can happen. That’s why the withdrawal must stem from self-respect rather than a ploy to win them back.

Timing varies: some move through these stages in weeks, others in months, but the sequence tends to be the same — confusion, recognition, light pursuit, panic, desperation, and then either breakthrough or retreat.

What unfolds biologically and behaviorally during the craving and pursuit phase can be surprising. When scarcity takes hold, intrusive thoughts begin. Random moments — during meetings, driving, scrolling — become filled with memories: laughter, support, shared inside jokes. Positive memories are idealized. Physical signals appear: restlessness, difficulty sleeping, appetite changes, or heightened phone checking and social media scanning. Seeing evidence of the other person’s happiness without them intensifies the craving.

Comparison behaviors show up next. They may try casual dating or distractions, only to find others deficient because scarcity has reframed the original partner as irreplaceable. Communication spikes transform into more elaborate messages: deeper disclosures, late-night calls, references to specific shared memories meant to rekindle connection. Then come grand gestures — unannounced visits, highly personal gifts, public declarations, or future talk that previously felt impossible. Promises to seek therapy, to communicate, to change can follow. Some mean it genuinely; others are motivated by crisis. Thus, a careful evaluation is necessary, because fear-driven effort often fades once security returns.

This craving-and-pursuit window is revealing: it proves capacity for care exists. Avoidance is not an absence of love but a fear response that can be overridden by emotional pressure. The real question is whether that pressure leads to lasting change or merely temporary compliance.

Before assuming scarcity is a foolproof tactic, be aware of risks and limits. The clearest danger is that some avoidants won’t chase at all. For these people, strong defense mechanisms make loss a safer option than vulnerability; letting go becomes preferable to the work of closeness. That outcome doesn’t mean a mistake was made — it signals unreadiness or unwillingness on their part.

Another risk is manipulation. Pulling back purely to influence behavior is a risky, moral, and emotional strategy. People can sense inauthenticity, and avoidants are particularly attuned to feeling controlled; perceived manipulation often accelerates withdrawal. The withdrawal must be grounded in authenticity and self-respect rather than a game.

Temporary change is also common. Intense pursuit during a crisis can revert once perceived danger passes. The test is post-crisis behavior: does their openness persist when things feel safe? If not, the change was only situational.

Desperate pursuit can cross boundaries: relentless calls, uninvited appearances, pressuring mutual contacts for updates. While sometimes framed romantically, such behavior can feel invasive or unsafe. It’s essential to have a plan for handling boundary breaches.

Finally, the emotional cost to the withdrawing partner is real. Creating scarcity requires giving up habitual levels of care and attention, which can be painful and trigger guilt or sadness. Staying resolute requires a clear sense of purpose. If withdrawal is half-hearted, short-lived, or inconsistent, it will reinforce the old beliefs and strengthen the pattern. True scarcity takes time to register; a single week of pulling back followed by a cave-in will confirm the old dynamic.

Taken together, scarcity can be a revealing mirror — not a wand. Used to protect energy and clarify needs, it can save months or years of waiting for someone who won’t change. If the other person rises to meet genuine boundaries, an honest conversation about building a healthy foundation can begin. If not, the result is clarity, which is itself a form of power.

When scarcity lands, transformation is possible. It can force an avoidant to confront the reality of emotional needs and crack the “I don’t need anyone” narrative. This attachment recognition is the first step toward change. Empathy can follow: feeling the anxiety of uncertainty provides insight into how their distance affected the partner. Value reassessment often occurs; qualities once taken for granted — patience, warmth, consistency — can suddenly appear precious. Scarcity can compel a confrontation with fear: to get back what matters, they must risk vulnerability, commit to openness, and engage in difficult conversations. Some will develop new communication skills because necessity demands clarity. In the best cases, priorities shift: connection becomes central rather than an afterthought, leading to tangible changes like more presence, planned intimacy, and inclusion in parts of life previously closed off.

Not every avoidant converts. For each person who evolves, another slips back into old habits when the threat ends. The measure to watch is whether change persists beyond the panic phase. If improvements only occur while fear of loss is acute, that reflects temporary crisis management rather than genuine transformation. If new behaviors hold after security returns, that indicates real growth.

Here is the fundamental takeaway: scarcity can wake an avoidant up and prompt pursuit, vulnerability, and possibly transformation. But it is not a method to compel love. It is a diagnostic mirror, equally revealing about the one withdrawing. If, after authentic scarcity, someone consistently shows openness, effort, and reliability beyond the panic stage, that’s a sign they can grow. If they disappear or only show up until they feel safe again, that too is an answer — not a failure, but clarity. Understanding these dynamics is not about controlling another person; it’s about refusing to unravel for someone who cannot meet you. It’s about protecting time, energy, and emotional bandwidth. The person chosen for a life partnership should make one feel valued without requiring vanishing acts to prove worth. Healthy love doesn’t depend on a performance; it doesn’t require manufactured scarcity to survive.

The challenge is simple: if stuck in a push–pull with an avoidant, step back not to punish or win, but to evaluate. Ask whether needs are being met: do you feel safe, seen, and valued, or are you constantly scavenging scraps of connection? If the honest answer stirs discomfort, don’t ignore it. That unease is information demanding change — either in the dynamic or the relationship itself. One person should not serve as another’s security blanket while they learn to show up. Both partners deserve to be chosen each day.

If this message resonated, leave “I choose clarity” in the comments to acknowledge the intention: the aim is clarity, not control. For those ready to go deeper into attachment work, boundaries, and breaking the cycle, watch the linked video on rebuilding self-respect after an avoidant relationship. Life is short — don’t spend it waiting for someone else to decide you’re worth the effort. Decide that for yourself now.

Starve Avoidants of Love — Watch Them Chase You | Avoidant Attachment Style">

Starve Avoidants of Love — Watch Them Chase You | Avoidant Attachment Style">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

4 Powerful Emotional Stages Avoidants Face When You Finally Step Back | Avoidant Attachment Style">

ΑΥΤΟ ΑΠΟΔΕΙΞΕΙ ότι ένας ΑΠΟΦΕΥΚΤΙΚΟΣ Θέλει ΕΣΑΣ για ΠΑΝΤΑ (και σας ΑΓΑΠΑ βαθιά)">

ΑΥΤΟ ΑΠΟΔΕΙΞΕΙ ότι ένας ΑΠΟΦΕΥΚΤΙΚΟΣ Θέλει ΕΣΑΣ για ΠΑΝΤΑ (και σας ΑΓΑΠΑ βαθιά)">

Γιατί το τραυματισμένο σου ΕΑΥΤΟ λαχταρά ΤΑΞΗ">

Γιατί το τραυματισμένο σου ΕΑΥΤΟ λαχταρά ΤΑΞΗ">

Οι 5 Ανείπωτοι Κανόνες για να Κάνετε έναν Αποφεύκων Άνδρας να Επιθυμεί Τέλος μια Βαθιά Σύνδεση">

Οι 5 Ανείπωτοι Κανόνες για να Κάνετε έναν Αποφεύκων Άνδρας να Επιθυμεί Τέλος μια Βαθιά Σύνδεση">

">

">

I figured out why my Relationships kept Failing.">

I figured out why my Relationships kept Failing.">

Do Boundaries work on Narcissists">

Do Boundaries work on Narcissists">

Tips to Heal FASTER From Effects of Trauma (4-Video Compilation)">

Tips to Heal FASTER From Effects of Trauma (4-Video Compilation)">

Pornography is EXTREMELY dangerous to your Relationship">

Pornography is EXTREMELY dangerous to your Relationship">

This ONE Affection Hack Creates Unbreakable Bonds with Avoidants">

This ONE Affection Hack Creates Unbreakable Bonds with Avoidants">