Oh my god — nothing I do is ever enough. Wait, what did you just say? I said it doesn’t matter what I try; it’s never going to be sufficient. Is that really how you feel — that nothing you do will ever be good enough? Honestly, yes. Can I ask you something honestly? What did you hear me say before all of this started? You told me you were upset because you’ve been feeling disconnected from me lately. Right, but what did you actually hear in those words — what meaning did you attach to them? What narrative began to form in your mind, and what emotions came up when I said that? I don’t know. Work has been nonstop, and when I’m at the office I worry you’re angry I’m not home, and when I’m home I’m anxious I won’t earn enough to support us. It feels like no matter what I do it won’t be enough and I’m going to fail. I honestly had no idea you felt like that. I can imagine how suffocating that must be, and I don’t want to dredge up old wounds, but I’ve noticed how your father used to speak to you. Is that the kind of thing he said when you were a kid — that you weren’t enough? He didn’t always have to say it out loud; it was in every disappointed look he gave me. Even when I brought home A’s, the response was, “let’s see if you can keep it up.” When we lost the state championship it was, “well, what did you expect? You didn’t keep your eye on the ball.” I’m so sorry — it must have felt like nothing was ever going to be enough. I can’t imagine how painful that was, and I want you to know I believe you are enough. You don’t have to prove yourself to me. I’m not angry when you’re working hard; I appreciate what you do. I also need you to share these feelings with me, especially during conflicts, because that shame, doubt, and negative self-talk is powerful and won’t stay bottled up forever — it will find a way out, often in ways that hurt you or the people closest to you.

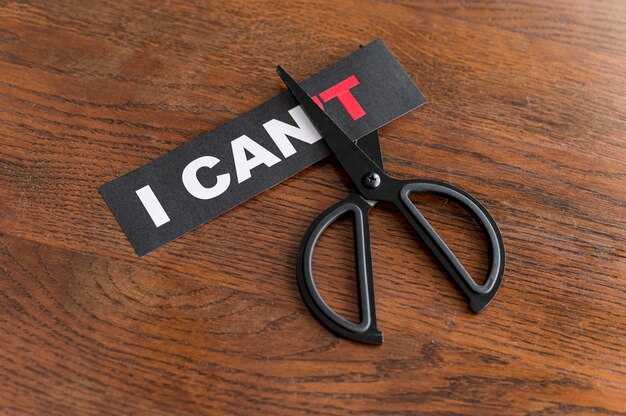

What helps after hearing “Nothing I do is good enough”

When someone says this, the immediate need is validation, safety, and practical tools. Below are communication strategies, short exercises, and longer-term steps to shift the pattern.

Communication steps for the partner

- Validate first: “That sounds really painful. I’m sorry you’ve been carrying that.” Validation does not mean you agree; it means you hear their experience.

- Reflect and clarify: “When you say nothing is enough, do you mean at work, at home, or in general?” Reflecting shows you’re trying to understand rather than fix immediately.

- Give specific, sincere appreciation: “I noticed you stayed late to finish the report — that helped the whole team.” Concrete praise counters vague feelings of inadequacy.

- Offer connection, not solutions: “I’m here with you. Would it help if we brainstormed small, manageable steps together?”

- Set a safe follow-up: “Let’s plan a check-in tonight so we can talk when we can both focus.” Regular, predictable conversations reduce anxiety about being judged.

What the person who feels “not enough” can try

- Name the thought: Notice and label the story (“I’m having the thought that I’m not enough”). Naming reduces its immediacy.

- Use evidence: List three concrete things you did recently that show competence or care. Small evidence builds a counter-narrative.

- Behavioral experiments: Try one low-stakes action that tests the fear (e.g., ask for feedback at work, accept help at home) and observe the outcome.

- Self-compassion practice: Talk to yourself as you would a close friend — “You did your best today; that is enough for now.”

- Limit comparison: Notice when you compare yourself to others and redirect attention to your values and goals.

Quick grounding and breathing (1–3 minutes)

1) Breathe in slowly for 4 counts, hold for 1–2, out for 6. Repeat 4 times. 2) Name 3 things you can see, 2 you can touch, 1 you can hear. 3) Place one hand on your heart and feel one reassuring sentence: “Right now I am safe; I did what I could.”

Short scripts you can use

- Partner to speaker: “Thank you for telling me. That must be really hard. I’m on your side.”

- Speaker to partner: “I’m noticing a voice in my head telling me I’m not enough. I don’t want to push that onto you, but I need you to hear it.”

- Repair after conflict: “I’m sorry I lashed out. I was feeling like I wasn’t enough, and I took it out on you.”

Longer-term practices

- Keep a “wins” journal: each day write one small thing you did well or a moment you felt competent.

- Practice cognitive restructuring: identify all-or-nothing thoughts, find alternative, balanced statements, and test them with evidence.

- Set achievable goals: break larger tasks into tiny, measurable steps and celebrate progress, not perfection.

- Consider therapy: approaches like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and compassion-focused therapy help reframe persistent shame and self-criticism. Couples therapy can help improve communication and repair cycles of blame.

When to get more help

If feelings of hopelessness, shame, or self-criticism become overwhelming, cause withdrawal, or you have thoughts of harming yourself, reach out to a mental health professional or crisis resources right away. You don’t have to handle this alone.

Small, steady changes in how you speak to each other and to yourselves can gradually loosen the grip of “never enough.” Start with curiosity and safety, name the story, and practice small experiments that build evidence for a kinder, more realistic view of who you are.

Practical Support: How to Respond, Set Boundaries, and Encourage Change

Respond immediately with one validating line and one concrete question: “That sounds painful – what happened just now?” then pause and listen without offering solutions for at least 60 seconds.

Use short, specific scripts to de-escalate: “I can sit with you for 15 minutes and help sort one thing,” “Name one example of what feels wrong,” or “When you say nothing is good enough, tell me one thing you tried today.” Keep your voice steady, slow, and low.

Set a time-limited boundary when emotional intensity spikes: state the limit, the reason, and the consequence. Example: “I want to support you, but I won’t stay in a conversation that includes yelling. If yelling continues for five minutes, I will step out and call you back in 30 minutes.”

Agree explicit behavioral boundaries and follow-through. Write down the target behavior, a measurable threshold, and the consequence. Example: “Target: complete two job applications per week. Threshold: fewer than two for two consecutive weeks → consequence: I will stop proofreading and you handle submissions yourself.”

Offer structured encouragement tied to measurable steps. Propose a one-week plan with three specific actions, deadlines, and short check-ins: Day 2: choose one small task; Day 4: attempt it; Day 7: review progress. Use a printed checklist and mark completed items together.

Give feedback that focuses on observable actions, not identity. Say, “You turned in the report late” instead of “You’re irresponsible.” Pair negatives with precise next steps: “Next time, tell me by 24 hours ahead if you need an extension.”

Use reinforcement for incremental gains: praise the action, specify what changed, and set the next small goal. Example: “You sent that email – good work. Next step: follow up in three days if no reply.”

Avoid rescuing patterns. Refuse to solve problems that the person can solve with support. Offer tools instead: a template, a list of local therapists, or a time-blocking method. Say, “I can show you how to structure the task; you’ll complete it.”

Teach one cognitive skill with a short exercise: when they declare “nothing is good enough,” ask them to list three specific outcomes from the past week and rate each 0–10 for control and effort. Then reframe one item from absolute to specific: “I didn’t finish” → “I completed X but not Y.”

Recommend professional options with clear next steps: call a licensed therapist for an intake within two weeks, ask about cognitive-behavioral therapy or dialectical behavior therapy for chronic self-criticism, and request a short waitlist or cancellation list to reduce delay.

Spot crisis signs and act immediately: talk of self-harm, hopelessness, sudden withdrawal, or reckless behavior. If present, stay with the person, remove dangerous objects, call emergency services, or contact a crisis line. Do not leave them alone if risk is high.

Document patterns confidentially. Keep a private log of incidents with dates, triggers, and responses for three months; use it in reviews to show progress or repeat issues when proposing changes or therapy referrals.

Use a shared accountability system: a weekly 15-minute check-in, a written plan with deadlines, and clear consequences for missed commitments. If the person refuses accountability repeatedly, reduce your involvement and redirect them to professional help.

Protect your own limits: schedule breaks, name your availability explicitly, and keep support practical rather than emotional rescue. If you feel drained after a session, take a 20-minute walk, call a friend, or pause further conversations until you recharge.

When progress stalls, switch strategy: shorten task size, increase external structure (set appointments, reminders), or involve a coach or therapist. Track changes in weeks, not days, and celebrate the smallest measurable gains to build momentum.

Proč říkají "Nic, co DĚLÁM, není dost dobré!!"">

Proč říkají "Nic, co DĚLÁM, není dost dobré!!"">

Relationship EXPERT reveals Secrets to Connection: Dr. Sue Johnson">

Relationship EXPERT reveals Secrets to Connection: Dr. Sue Johnson">

Obklopeni jste šikanátory? Skrytý důvod, proč je vpouštíte.">

Obklopeni jste šikanátory? Skrytý důvod, proč je vpouštíte.">

Chování vašeho partnera je způsobeno traumatem, ale i tak to není v pořádku.">

Chování vašeho partnera je způsobeno traumatem, ale i tak to není v pořádku.">

Nejsilnější Znak, Že Vás Stále Hluboce Miluje Vyhýbavý Člověk">

Nejsilnější Znak, Že Vás Stále Hluboce Miluje Vyhýbavý Člověk">

Pokud se během konfliktu vypnete, podívejte se na tohle">

Pokud se během konfliktu vypnete, podívejte se na tohle">

Pokud Váš partner používá tyto fráze, je to vyhýbavý typ.">

Pokud Váš partner používá tyto fráze, je to vyhýbavý typ.">

Until This One Shift Finally Made the Avoidant Come Back | Mel Robbins Motivational Speech">

Until This One Shift Finally Made the Avoidant Come Back | Mel Robbins Motivational Speech">

Pro léčení je rozumná akce silnější než smutné příběhy">

Pro léčení je rozumná akce silnější než smutné příběhy">

Partner by má znát tvou minulost — ale co když si jen randíš?">

Partner by má znát tvou minulost — ale co když si jen randíš?">

PODVÁDĚNÍ je pro SEBESTŘEDNÉ ZBABĚLCE (jako já)">

PODVÁDĚNÍ je pro SEBESTŘEDNÉ ZBABĚLCE (jako já)">